“What did your mom die of?”

“Three bullets.”

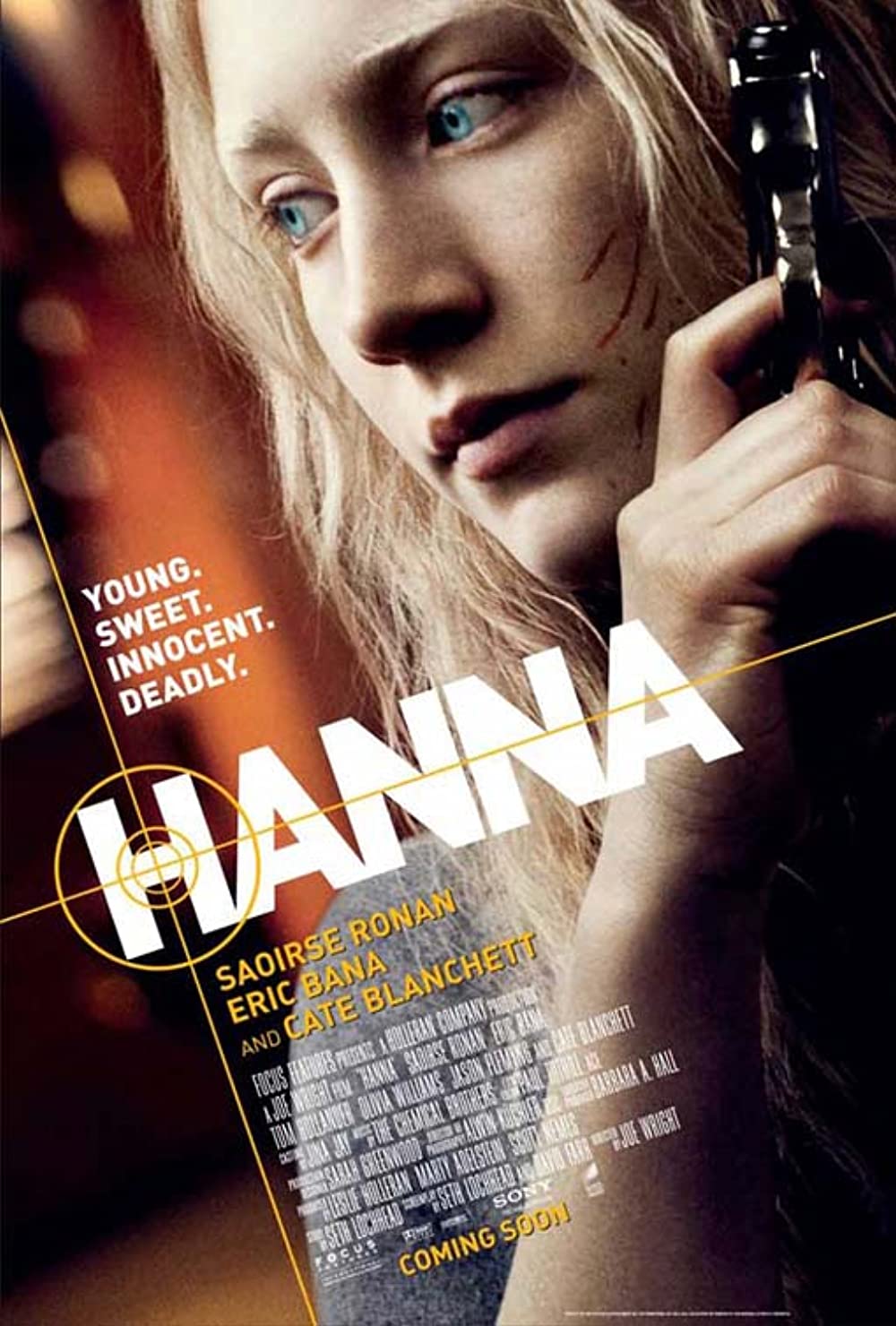

It feels disingenuous to say so, but Hanna would be excruciatingly silly if it didn’t star Saiorse Ronan in its title role. Outside of her majestic and layered portrayal of a ruthless killer raised to survive at all costs, and the kinetic energy of its endless chase sequences, it simply doesn’t have much to offer. Not that those plusses are anything to scoff at. Indeed, many filmmakers would sacrifice a limb to cast Ronan and be able direct action scenes with as much flair as Joe Wright does here. There are several stretches where Alwin H. Küchler’s dizzying camerawork and Ronan’s lithe athleticism generate a wonderful adrenaline rush. However, once the dust settles, it becomes painfully evident that the entire enterprise is built upon its aggressive style and exotic locales and has no substance beneath its considerable surface level charms, essentially amounting to a mid-budget iteration on Run Lola Run that adds the Chemical Brothers and a bogus fairytale-meets-spy-thriller frame story but lacks Tykwer’s philosophical underpinnings and multimedia approach.

Deep in the snowy Finnish wilderness, Hanna lives with her father Erik (Eric Bana), an ex-CIA operative who has trained her to be a ruthless survivalist since she was an infant. Now a teenager on the verge of adulthood, Hanna is fluent in numerous languages, an expert in various forms of armed and unarmed combat, and brimming with ideas gleaned from a one-volume encyclopedia that has taught her about the outside world. (Somehow, later on, she proves to be an expert at google-fu despite never having seen a computer before.) Erik harbors knowledge that makes him a threat to America’s national security, and so, in a moment of contrived storytelling, he gives Hanna a transponder that will alert the CIA to their presence when pressed. (Seriously, why does he have a direct connection to his arch enemy in the first place? And why, after sixteen years of successful evasion, does he not at least contemplate trying to slip back into society unnoticed?) Of course, Hanna presses the magic button, beginning a globetrotting journey that will take her from secret underground facilities to hostels in third world countries, labyrinthine shipping yards, and abandoned theme parks. It will also result in lots of PG-13 bloodshed.

As her implausible adventure begins, Hanna follows her father’s carefully laid plan that was intended to culminate in her assassinating his former handler, Marissa Weigler (Cate Blanchett with a ridiculous Southern accent), the CIA officer who was responsible for the death of Hanna’s mother (Vicky Krieps). After infiltrating the government compound, she manages to kill an impersonator, and, believing she has completed her mission, escapes and sets out to join her father in Berlin. But she soon finds herself stalked by a trio of hitmen led by Isaacs (Tom Hollander) as she hitches her way across Europe with a friendly tourist family (Olivia Williams, Jason Flemyng, Jessica Barden, Aldo Maland) and discovers all the technological wonders that she’d been deprived of all those years. (Let’s ignore the fact that Hanna’s “adapt or die” mentality does not extend to learning how to use light switches, electric tea kettles, and showers.)

A light techno-thriller backstory eventually emerges concerning Hanna’s mysterious upbringing—essentially the only story the film feels obliged to offer—but it is clearly an afterthought, and at all points forward momentum and visual flamboyance are favored over storytelling. Well, maybe that’s uncharitable. The main character is, by design, essentially unknowable, so at least there’s an excuse for Wright’s style-over-substance approach regarding Hanna. And Ronan, with her pale skin and determined lack of sensuality, manages to demand our attention despite Hanna’s personal opaqueness. However, outside of Hanna, there’s not a compelling character in sight. At certain points—specifically, the emphasis on the villains’ weird eccentricities (Weigler is obsessed with her teeth, while Isaacs owns a drag club and cannot stop whistling even when trying to be sneaky) that prove completely meaningless—you get the sense that Wright is forcing idiosyncratic touches for their own sake and failing to consider how these flourishes will integrate into the whole.

When the picture slows down—which it must, however infrequently, to maintain the illusion that it actually gives a rip about its narrative lest we realize it is actually a two-hour music video—it rapidly begins to drag and show its seams, exemplified by Hanna’s ridiculous romantic mishap with a teenage boy who wants to smooch after an awkward date. What’s most disheartening about the film’s myriad flaws is that its unique characterization and superb action are perfectly capable of carrying a sublime thriller. All it needs is a coherent framework and the right tone in its calmer moments. It gets neither, and the garbled pile of clichés, edgy quirks, faux-sentimentality, and shallow supporting characters that are offered regrettably undercut what might have been something special.

But if Hanna is all surfaces, at least Wright gives them a dazzling polish, as evidenced by his technically challenging tracking shots, impressively orchestrated fistfights, and lush set designs (the underground maze of the CIA facility, the fairytale theme park), which are all uplifted by the pulsating Chemical Brothers score.