“I always felt that thief next to Jesus got off lightly.”

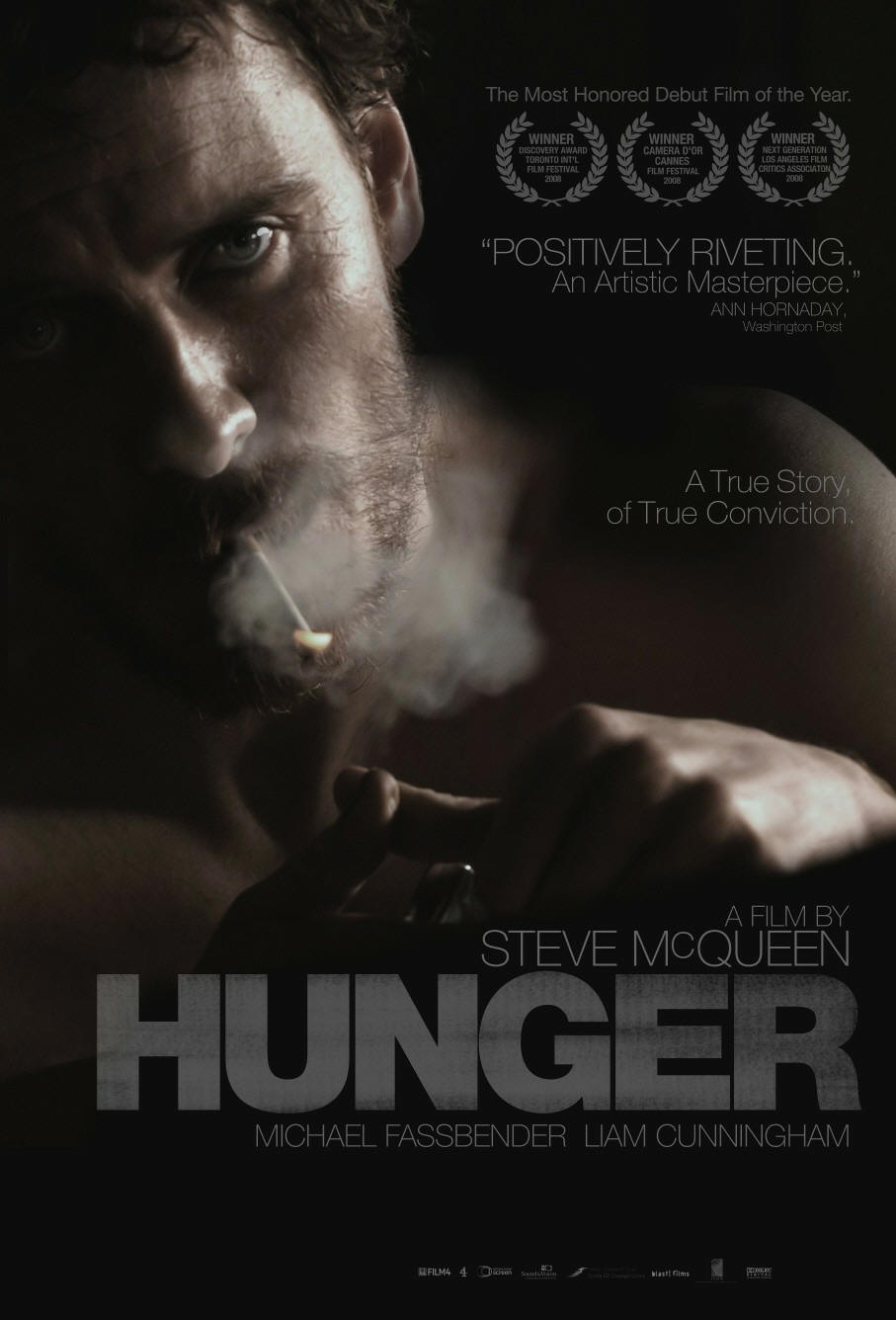

The centerpiece of Steve McQueen’s Hunger is a lengthy conversation between Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbinder), an imprisoned terrorist about to engage in a hunger strike that will kill him, and Father Dominic Moran (Liam Cunningham), a priest who is trying to talk him out of it. Approximately twenty minutes in length, the conversation ranges from the morality of Sands’ decision, to the isolated principles that drive him, to the gulf between their belief systems and life experiences, to formative moments in the young Sands’ childhood. It’s a brilliantly written scene (McQueen co-wrote with playwright Enda Walsh), but even more stunning is that the bulk of it is delivered in a single, static, seventeen minute long two shot as the pair sit in an empty room smoking through a pack of cigarettes.

On either side of this tranquil, utterly engrossing conversation, McQueen places bookends jarringly dissimilar to it. Employing sparse dialogue and consistently haunting imagery, the opening sequence depicts the frightening dynamic inside Northern Ireland’s Maze Prison in the early 1980s. With the “blanket” and “wash” protests in full swing, the prison is in absolute pandemonium as the inmates (Liam McMahon, Brian Milligan) refuse to wear clothing or maintain their hygiene. They smear feces on the walls, and pile up food to attract maggots and divert their urine into the hallways. The guards (represented by a bruiser played by Stuart Graham), respond with harassment, humiliation, and brutality, but it seems that these men are unbreakable.

The first half hour is abjectly distressing. Even so, the extended coda, which documents Sands’ death by starvation, is much worse. Fassbender reportedly went on an extreme diet for months, and the result is gruesome and grotesque. He’s a walking cadaver, his emaciated physique perhaps a more startling “achievement” than Christian Bale’s similar transformation in The Machinist. His ghastly appearance is augmented by a collection of oozing lesions that gradually enlarge and multiply as his nutrient-starved body breaks down.

McQueen captures the most inhumane of these depravities in a direct style marked by agile-but-not-handheld camerawork and a dearth of cuts that serves to put the viewer inside the prison compound and render the environment and atrocities viscerally tactile. Next to the aestheticized violence of blockbuster films, the cavity searches and forced haircuts of Hunger are astonishingly brutal and unforgettable. Elsewhere he does some neat things with flashback, montage, silence, time, split screen, and unconventional visuals (at one point he traces a crack in the ceiling to indicate Sands’ atrophied mental faculties) that are as effective as they are academically interesting.

If the characters are abstracted out to symbols and the situation reduced to the bare essentials of its hellish scenario, that can only be for the better, as a quick scan of the film’s political backdrop (always a risky idea, the quick scan) would suggest that exploring its misguided subjects a scintilla further than McQueen does would make it a wholly different, less impactful work. Radio snippets provide a minimal context and a short scene illustrates the IRA’s ruthless methods, but the general focus is not on Sands’ terrorist activity or his foolish demands, but on his conviction to follow through on his decision and the humane treatment afforded him by his caregivers.