“You’ve been up here too long man. You’ve lost your marbles.”

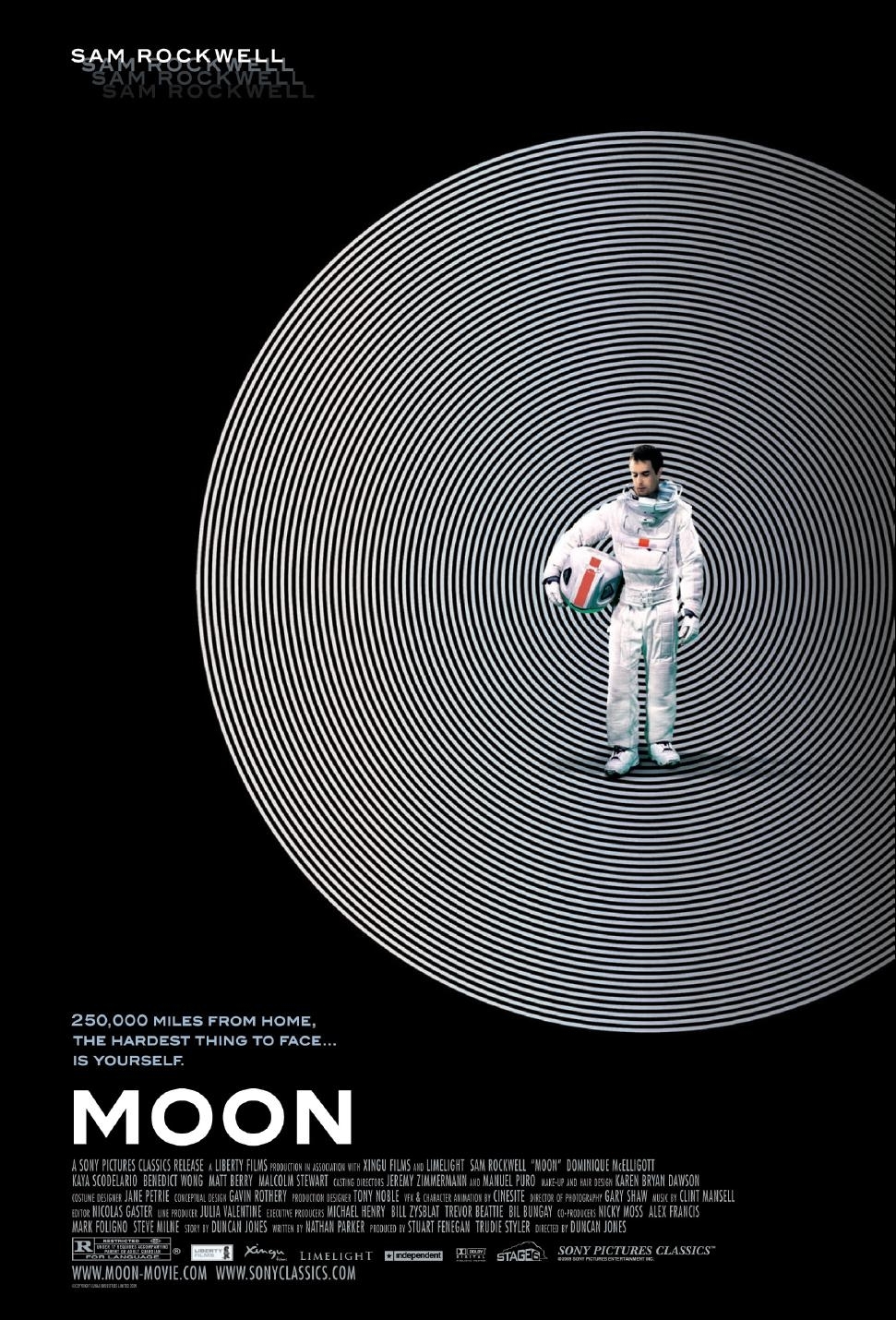

Before Star Wars permanently altered our expectations for what science fiction cinema should be, the genre was characterized as much by its cerebral entries as by space operas. In these films, we find ourselves off the beaten path, often thinking about the film’s concepts long after the credits rolled, sometimes challenged as much by their cinematic presentation as their topical subjects. There’s the unavoidable towering colossus of 2001, but also films like Silent Running, Solaris and The Man Who Fell to Earth. The general trend after the explosive success of Star Wars favors streamlined narratives over ruminative or meandering ones. In those films, your main task as a viewer is to obsess over which characters will betray one another in the next movie, or which are related to one another, rather than, for example, to contemplate the reality of your own existence or the destiny of mankind. I won’t lay all the blame on Lucas, though, and I’m speaking of a trend that has obvious counter-examples. But even though I like space opera just fine, I have a distinct preference for that headier brew of sci-fi. Moon, the debut from Duncan Jones (née Zowie Bowie, son of David), plucks many familiar elements from those fond classics in an attempt to revive the defunct genre. It’s a deliberate throwback, a defiant homage to the days when sci-fi was still the realm of the nerd, and being a “nerd” wasn’t mainstream like it is now. It looks the part and acts the part of the vintage sci-fi film. It also delightfully ticks the box as “indie,” punching in at a cool $5M budget. That’s a lot of stuff stacked up in the pro column, and the few minor issues that present themselves barely dampen my enthusiasm for Zowie’s first film.

If you’re interested in that strain of science fiction that gives rise to wonder and contemplation—the kind that you find yourself still thinking about intermittently years after you’ve encountered it—then you need a certain amount of our known reality to be present in the story. It’s not as simple as practical effects (though they go a long way) or the assumption that Coca-Cola or Disney will still be popular brands when we live on thousands of planets. You also don’t necessarily need human characters. It’s not an exact science, but there are clear examples of what you can’t do and still retain a grounded connection. The best way I can think to describe it is that we need to be transported just past the fringes of our current reality—far enough to temporarily believe in the mysteries presented to us, but not so far that we lose any connection with the characters. The trick is to find the sweet spot, grounded in reality with some subtle shifts that allow us to explore something from a unique angle. Moon tries to land right in that sweet spot.

Concerning a contractor stationed on the moon for a three year stint harvesting Helium 3, the central question that Moon asks is to what lengths we would go to harness a sustainable energy source. I won’t go into details (check out from Scientific American below), but the energy harvesting operation that is overseen by the film’s primary human character has been proposed by legitimate scientists as a possible solution to our energy woes.

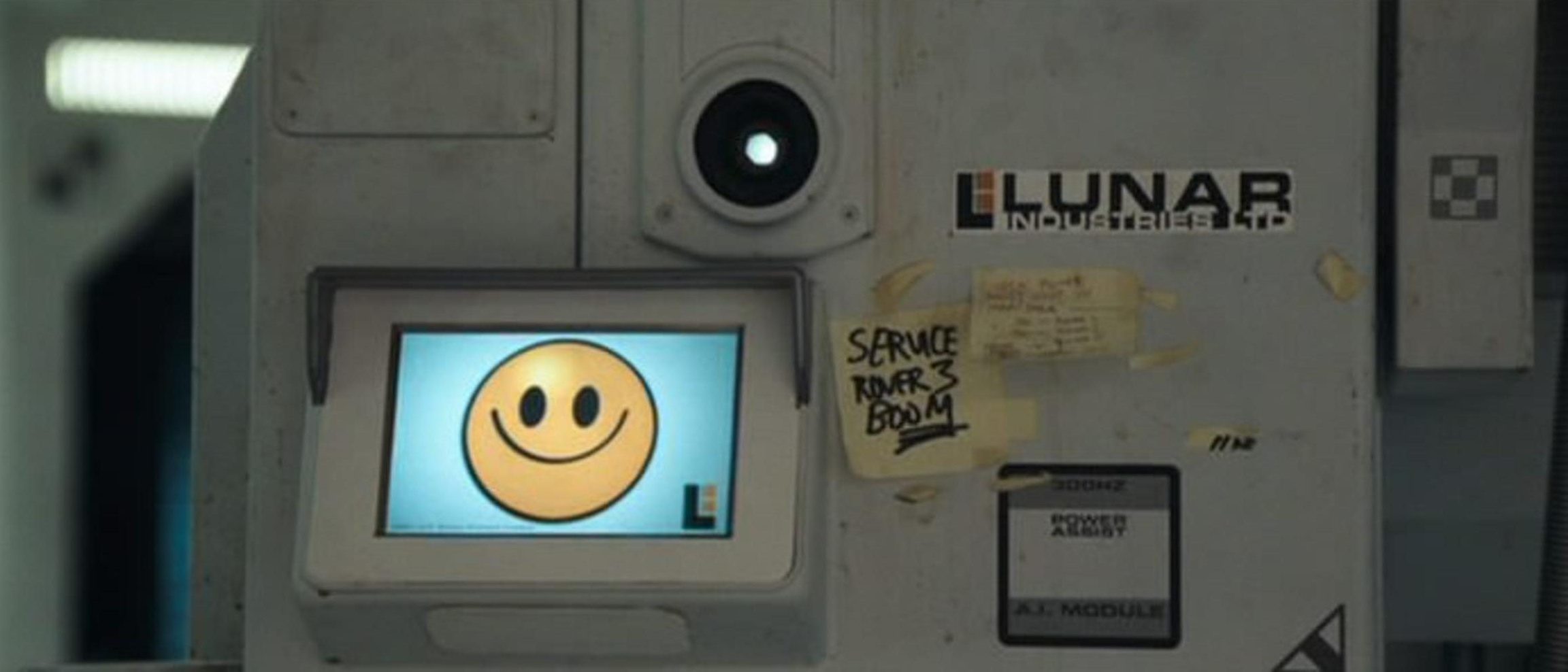

So we’ve got our first little extension into the unreal, fleshed out by superb miniatures and a 360° moon base. (Keep in mind that the lived-in, space junk vibe of the set design—which clearly recalls Alien—was achieved for like 2% of the budget of those space operas.) The film opens with Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) plugging away at his duties as his contract nears its end. As the sole human at the mostly automated station, he’s going through the motions, but you can tell that his body and mind have been worn down by the years of isolation. His only companion is a mobile computer named Gerty (voiced by Kevin Spacey) whose facial expressions consist of stock emoticons. Live communications are down so Sam’s only correspondence with his wife occurs via recorded video messages. With only a few weeks left before his trip home to earth, Sam begins experiencing hallucinations. One day, while driving a rover out to one of the harvesters, a hallucination causes him to lose focus and crash the rover and lose consciousness. He wakes up inside of the station, a bit wobbly, but seemingly recovered—maybe even healthier than before. He’s suffering from amnesia, and can’t seem to puzzle out what has happened. How exactly did Gerty, who is attached to the ceiling of the station, retrieve him from the crashed rover? Why can’t he remember anything? Why is Gerty monitoring him so closely? Gerty won’t even let him go off-base until he sabotages a gas line and convinces Gerty to let him do a maintenance check-up. When he discovers a copy of himself in the crashed rover, his world goes topsy-turvy.

At this point in the film, Moon is wide open—it’s successfully pulled a rug out from beneath us by introducing a clone of Sam. It could have gone any number of directions, but it strives to present a portrait of a mentally deteriorating man, with only himself for company in a weirdly literal sense. The New Sam accepts his fate right away. He’s clearly a clone, but the Original Sam—he struggles. At first, he holds out that he’s the true original, but as his body begins to malfunction, he comes to realize that the three year contract is a result of the lifespan of the clone body. He won’t survive much longer. This sad reality is cemented in an emotional scene where he manages to get a live call through to earth, and talks to his fifteen year old daughter, with whom his wife was pregnant when he left… “three” years ago. Unseen but heard is the OG Sam speaking to his daughter. Does he know there are clones of himself still up on the moon? Rockwell handles this complex double role with dexterity—arguing with himself, switching demeanors, showcasing a wide range of emotional states of mind. We never have to guess which Sam is which, and the unexpected dearth of action only works because of Rockwell’s audacious performance.

While the screenplay does a good job of presenting us with the situation, it shies away from any moralizing or dramatic twists, choosing instead to linger on the interactions between the two Sams. It’s leisurely in its pace, and never seriously explores any tangential issues like workers’ rights or the ethics of cloning itself.1 Instead, the focus is on the first Sam’s acceptance of his false memories and imminent death and his internal struggle to determine what his “life” could possibly mean after the revelation of his origin.

After the clones meet one another it really becomes the Sam Rockwell show and it doesn’t have the brainy playfulness of the early portions. It becomes more of a psychological drama than a brain-tickling science fiction film. The pacing is noticeably slower in the second half as Sam gets into his own head. I think that screenwriter Nathan Parker could have been a little bit more adventurous in the latter portion of the film, but I prefer the brooding, lingering style that was employed to an action-packed one that would have been silly and over-the-top, so I’ll hold my tongue.

While I have some issues with Moon, it was new when I was cinematically coming of age. I saw it before I saw most of the films that it was inspired by, and I wasn’t smart enough to identify some of the things that I dislike about it now. It holds a special place for me for its vintage style, provocative ideas, and modest budget—things which still draw me to films all the time. It gets so much right with the presentation, practical set design, and isolated-in-space premise that I can forgive its few shortcomings. Viewed as a straight faced homage, I’m more than content with what Moon has to offer. Plus, let’s not forget this was a debut feature, albeit by the son of one of the most well-known names in entertainment history.

1. There’s a potentially gargantuan logic gap in the writing that needs addressed. Apparently, Lunar Industries uses the clones because it is too expensive to train and ship a new person to the moon every three years. This is super implausible. You’re telling me it’s cheaper to create technology to clone people, implant memories in them, and then keep them cryogenically frozen, than to just send a new person every few years? Further, if you can implant memories, then you don’t need to train people. I could go on, but you can see this was a rather large oversight. I think a viable answer to this is that in the future, those technologies are ubiquitous and cost-effective. Of course, that takes us further from the grounded reality that keeps Moon in that sweet spot—but, it keeps the focus solely on the ethical harm done to the Sam clones by not telling them that they’re clones and letting them die thinking they’re boarding a ship for home.

Sources:

Matson, John. “Is MOON‘s sci-fi vision of lunar helium 3 mining based in reality?”. Scientific American. 12 June 2009.