“People here just try to survive, that’s all. Some make a little moonshine, don’t really harm nobody.”

Rolling Stone magazine ranks Johnny Cash’s “I Walk the Line” as the greatest country song of all time. Its themes of marital fidelity and personal responsibility were a reassuring love letter to his first wife that he was remaining true while on the road. Legend has it that he wrote the song in a mere twenty minutes while on tour with Sun Records labelmate Elvis Presley, a budding star who had already begun his meteoric rise to fame and was no doubt surrounded by temptations of all sorts. “I Walk the Line” became Cash’s first big hit and soon after he began to fall victim to many of the vices that he swore to avoid—namely alcohol, amphetamines and women. Vivian Liberto filed for divorce from Johnny Cash in 1966 citing those very reasons.

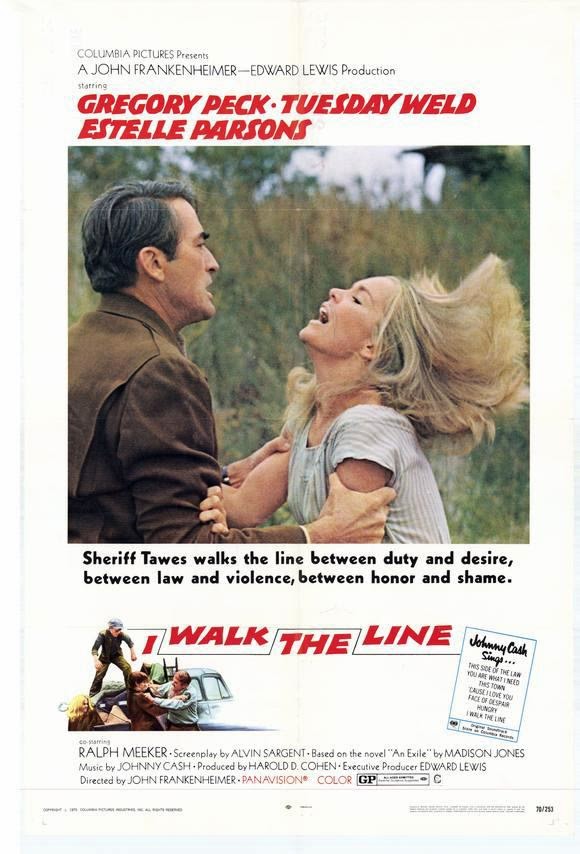

Fourteen years after the song’s release John Frankenheimer made a film that shares its name. It features an all-Cash soundtrack—some new songs (“Flesh and Blood” became a hit), others re-recorded especially for the film. But just as Cash’s behavior deviated from the promises made in his song of devotion, so the movie eschews the song’s narrative for one of vice and internal moral struggle. Gregory Peck stars against type as a wayward sheriff lured into sin by a moonshiner’s daughter half his age. He oversees a small, derelict town characterized by its dilapidated structures, abandoned cars, barren fields, and dead-eyed porch-sitters. Crime happens but more often he’s asked to weigh in on property line disputes and administrative issues. Each night, he steels himself for another round of terse dinner conversation with his simple family and his wife’s daily regurgitation of the latest Reader’s Digest article that she’s consumed as absolute truth. Though appearing resolute and upstanding—and maybe he once was—Sheriff Tawes has grown bored of his job and unremarkable domestic life and invites diversion.

It’s no surprise then when he becomes smitten by the nubile Alma McCain (Tuesday Weld). Their first encounter happens by chance when ten-year-old Buddy (Freddie McCloud) steers the McCains’ truck off the road and then flees into the bushes, leaving his sister to sweet talk the Sheriff. But when Alma shows up in town claiming her brother Clay (Jeff Dalton) ditched her—and if it wouldn’t bother the Sheriff too much, and if he was headed that way, could he please drive her home?—you get the sense that a nefarious plot is brewing, that maybe Alma has done this before. Tawes is quickly swept off his feet by Alma’s uncultured charm, mischievous smile, and youthful vigor. It’s only once he’s been seduced into a hotblooded affair that he discovers his mistress’s family doesn’t make their living crafting pot handles as he’d been told. Rather, they’re regionally notorious for their itinerant moonshining. They’ve got a functioning still hidden on their rundown property within the Sheriff’s jurisdiction. Caught in a web of his own making, he tacitly agrees to an arrangement with Carl McCain (Ralph Meeker), essentially renting Alma’s companionship in exchange for a blind eye turned toward their unlawful activities.

But that’s not an act that can be kept up for long. By the time an excise official (Lonny Chapman) arrives in town vowing to eradicate the production of moonshine, Tawes has given up on righteousness. He’s become so hopelessly committed to Alma that open suspicion from Deputy Hunnicutt (Charles Durning) and his wife Ellen Haney (Estelle Parsons) only worsen his carnal desires, as if the proximity to exposure increases his pleasure. But whatever feelings Alma has for the Sheriff are trumped by her loyalty to her family, causing a rift to form between the adulterous couple. She’s caught off guard when he suggests they run away together, that they get on a jet plane and head to California. “You’ve got your people, and I’ve got mine,” is how she puts it. If it wasn’t crossed before, the nebulous point of no return is left in the rearview when the Sheriff helps the McCains bury the body of a dead man who had stuck his nose too far into the family’s affairs. Now he is no longer turning a blind eye. Probably not even “aiding and abetting.”

Critics didn’t really care for I Walk the Line when it was released. They thought Cash’s music was misplaced and Peck was a misfit as the lead. I find both of these complaints off the mark. Cash’s recognizable baritone might be so prominent that it is momentarily distractive, but I found that his almost-just-talking style and the absence of any other music gives the whole thing a consistent backcountry flavor.1 And Peck might not be the most adept at visibly portraying inner turmoil but his stiff style adequately presents a tightly wound man growing evermore detached from the life he is familiar with as he plunges further into the depths of his newfound passion. Those battles happen internally, presenting themselves to us when he’s blankly staring at his pleading wife or at the ceiling while she tries to get close to him in bed. His uptightness is splendidly juxtaposed with the boisterous presence of Durning and Weld’s charming lack of sophistication.

Like the nameless residents who watch this drama unfold before their eyes, I Walk the Line does not judge its characters, none of whom are free from sin. There’s the Sheriff’s elaborated list of misdeeds; Alma’s lies about their chance encounters, not to mention her omission of the fact that she has a husband in prison; Hunnicutt’s attempted rape of Alma; Carl McCain’s illegal business and perhaps incestuous relationship with his daughter. (It seems just about everyone had the hots for Tuesday Weld.) These are all broken people. Perhaps the only exception is the impressively performed Ellen Haney who seems eager to forgive her husband’s offenses—even on an ongoing basis—if it means he will remain the family’s breadwinner. Parsons portrays Ellen as simultaneously assertive and submissive, making the tense scenes between the married couple extremely unsettling. Several times she is flat out ignored when she tries to generate conversation as the Sheriff simply stares off into the distance. Finally, when he deigns to offer a short, thoughtless response, she latches onto as if it were a carefully considered reply and uses it as a segue to reiterate how eagerly she supports his professional ambition. At another point, the two families attend a drive-in screening of Hook, Line & Sinker at the same time. The married couple endure an awkward ride home while the Sheriff grits his teeth, vexed as he eyes Alma in the back of the truck in front of them.

The tangible sense of place is effortlessly conjured by shooting on location in Tennessee and allowing the actors to move around in their backwoods environment. The town square, the county courthouse, the hardware store, the dam, the bridge, the crumbling remains of houses—these weathered and worn locations tie this film to the region and era without a hint of artificiality. Cinematographer David M. Walsh’s patient camerawork and careful framing capture the backwoods setting and the slow burn of the drama. He also crafts what I believe is a double split diopter shot (see above).

Sometimes people do inexplicable things. I Walk the Line doesn’t try to justify the actions of its characters nor does it offer sufficient backstory for us to view them as foregone conclusions (even if we can see the Sheriff’s pursuit of Alma is ill-fated from the start). Its five most prominent characters—those played by Peck, Weld, Meeker, Parsons, and Durning—are all written with a perfectly balanced ambiguity that allows the excellent performances to steer the audience. I Walk the Line is a haunting small-scale drama that seems to have been overlooked and deserves some reappraisal.

1. The style of Cash’s music works well, but I couldn’t help but think how perfectly Tom T. Hall’s ‘(Margie’s At) The Lincoln Park Inn’ fit the theme of the film. I suppose that song could become a movie of its own.

Sources:

Beck, Ken. “‘I Walk the Line’ laid an egg in 1970”. The Wilson Post. 26 October 2020.