“Wiggle your big toe.”

Every time I travel for work, which is almost always to a manufacturing site adjacent to a medium-to-large-sized city, I scope out the local movie theaters’ showtimes and try to convince myself that after a long day’s work I’ll muster up the gumption to sidle downtown, buy a ticket, and plant my bottom in front of the silver screen; a distressingly rare occurrence now that my fatherhood era is in full swing. If I had to guess, until last week I was approximately 0/20 on going to the movies while on a work trip—coworkers want to grab dinner, an early flight the next morning, a theater twenty minutes away from the hotel, the fact that I haven’t slept through the night in my own home in about two years and thus crave the unbroken solace of sleeping in a hotel bed by myself. Excuses for an early night are not hard to come by. Last week, unexpectedly, all the stars aligned. I was by myself for the evening, staying at a hotel 0.6 miles from a theater, and had a leisurely drive ahead of me the next day (which ended up being mostly on snow-covered roads in a 2WD car, but I digress). The last thing I needed was a compelling movie to get me to hand over my hard-earned cash. Avatar: Fire and Ash (2025) isn’t out yet and Predator: Badlands (2025) has been out so long already it had been relegated to a single late night showing… but wait, what’s this? Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair starting thirty minutes from now? And I’m twenty minutes away from the theater? I hadn’t even heard Tarantino dug it out of the vault after showing it at Cannes in 2006 and at his own theater sporadically thereafter. A short jaunt in the car, a frantic navigation of a three-story mall, and a quick scarf of footlong Nathan’s hotdog later and I was seated in a fancy reclining seat suddenly ready to relive the combined glories of Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) and Kill Bill Vol. 2 (2004), giddy as when I was a teenager first discovering the lavish genre homages of Tarantino for the first time but now halfway educated on the influences that shaped his taste and style.

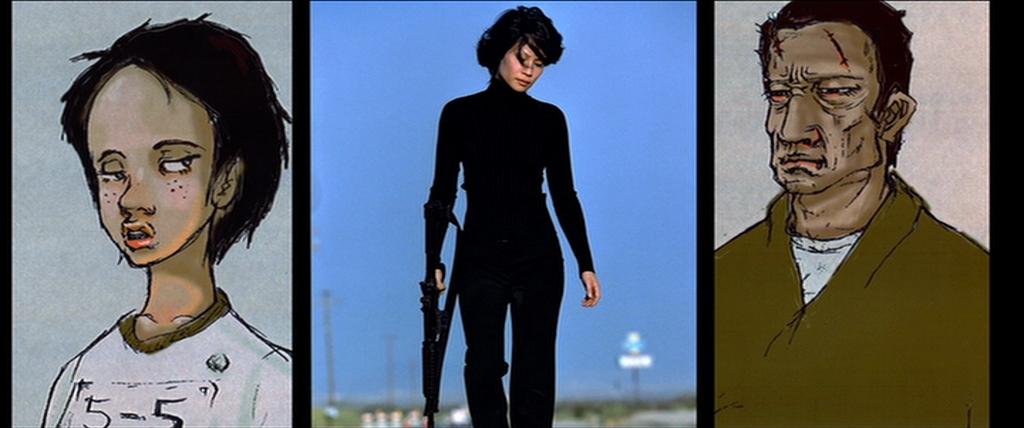

And taste and style really are the key drivers here, because Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair is best understood not as a revenge epic nor a supreme amalgamation of genre cinema, folk legends, myths, and esoterica nor an action movie critique of misogynistic attitudes nor even as two incomplete partial films finally sutured together as intended, but rather as an act of curatorship elevated to the level of auteurism. Tarantino’s whole deal, which he’s circled for thirty-odd years now, is that there was never anything inherently disreputable about grindhouse cinema, spaghetti westerns, samurai and kung fu movies, slasher and body horror flicks, animated films, or seventies exploitation more broadly; what often limited them was constraints of resources, time, and technical mastery rather than a lack of imagination or attitude. Kill Bill is what happens when someone who has spent a lifetime internalizing the grammar of those films decides to remake them all at once, skating clear of parody or overt quotation (but certainly not holding back on reference or homage) in favor of a maximalist elevation of the raw materials, bringing to bear virtuoso camera movements, surgical editing, and a screenwriting chutzpah so brazen that the film pauses its own climax for a monologue about Superman’s secret identity and a flashback to a standoff over a pregnancy test. Watching it after having seen more of the director’s influences—Lady Snowblood (1973) most obviously, but also lots of De Palma and Kinji Fukasaku (to whom the film is dedicated)—only reifies the film’s success. Even the images that feel copy-pasted are placed into a structure so wild and elastic that it can accommodate anime origin stories for its villains, a sudden emotional devastation in the midst of a raunchy-comedic reverse slasher episode, and a revolving door of supporting characters who blaze through a single indelible scene each before vanishing forever.

What distinguishes this everything-and-the-kitchen-sink approach from later, more shiny and corporatized retro-minded blockbusters, aside from its craftsmanship—which is a huge thing to set aside considering how slickly the film is shot by Robert Richardson, how wonderfully it is edited by Sally Menke, how intricately the soundtrack is worked into its bravado character intros and choreographed action, how gleefully those headless bodies and severed limbs spurt fake blood all over the set, how euphorically the use of split screens renders vastly disparate scenarios, how beautifully the screenplay uses mirroring effects, and perhaps most importantly, how adroitly Uma Thurman (and her stunt double Zoë Bell) manages the athletic and psychic extremes to fully embody all of the dimensions of one of the great female action heroes—is its sincerity. This is an unabashedly fun movie with giddy cartoon violence and grand emotional gestures, which means it’s inherently at least kind of silly, but Tarantino directs it without a scintilla of shame or irony; he believes wholeheartedly that his extravagant homage is awesome and if he didn’t believe that it wouldn’t be.

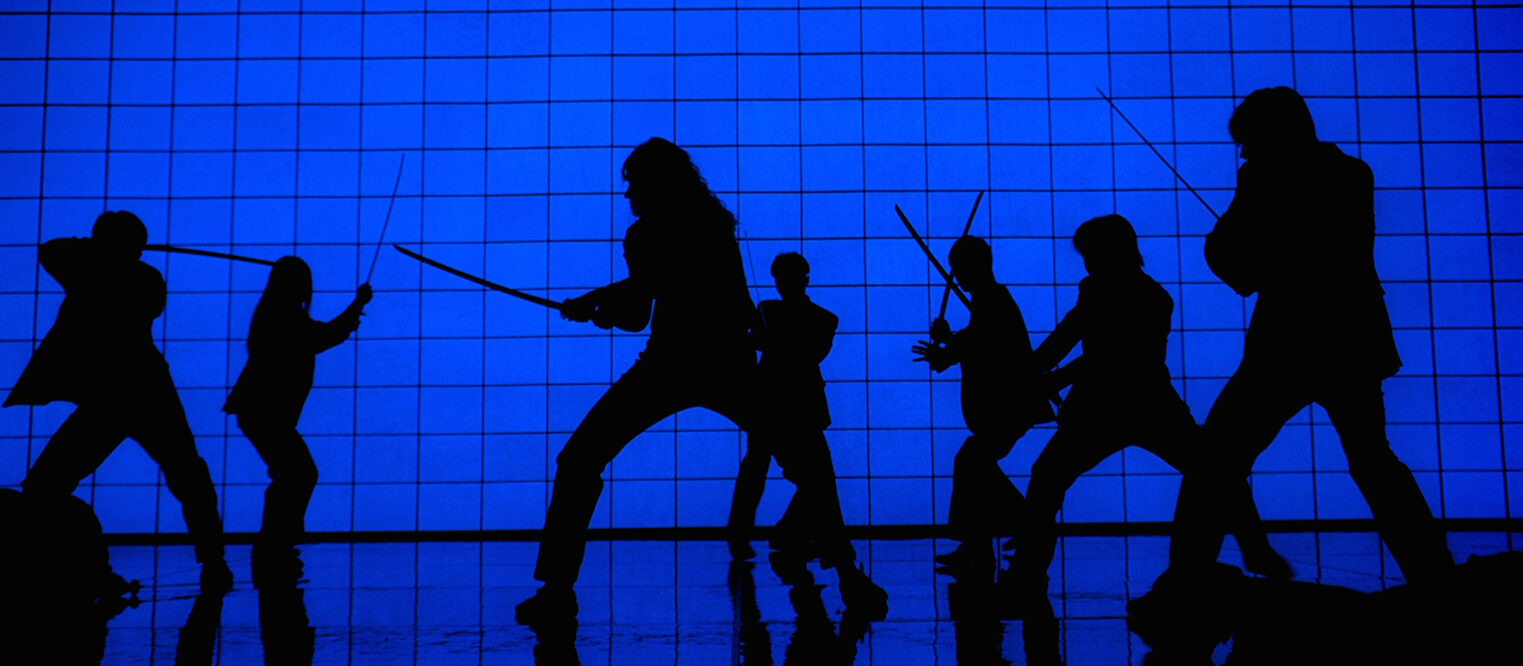

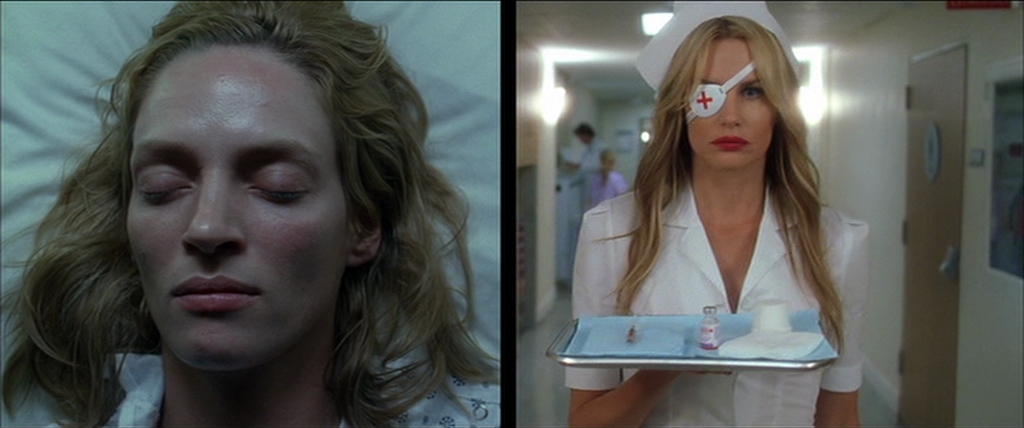

Thankfully, he does fully commit to his vision and it is totally awesome. The inspired anime backstory is both excessively gory and distressingly sad, as a child watches her parents’ back-to-back murders from a hiding place; likewise, Beatrix’s own presumed-dead child hangs over the narrative as an undercurrent to the surface-level revenge quest for her own botched murder that left her comatose with a steel plate in her head to be repeatedly raped by a hospital attendant (Michael Bowen) and his buddies. These heightened emotions are then distilled and channeled into the iconographic, picaresque, and nonchronological story of the Bride (Thurman) rising from her lowest point to systematically mete out vengeance on those who gunned her down during her wedding rehearsal—namely pimp/cult leader/master assassin Bill (David Carradine) and his former assassination squad, including sadistic, one-eyed killer Elle Driver (Daryl Hannah), retired beergut bouncer Budd (Michael Madsen), yakuza leader O-Ren Ishii (Lucy Liu), and killer-cum-homemaker Vernita Green (Vivica A. Fox), an order to which Beatrix belonged until she suddenly didn’t—with the wild, pop-mythical episodes of her journey stirring up a sense of communal jouissance that resonates on all its registers. The one-shot chapters with Sonny Chiba’s master swordmaker and Gordon Liu’s ancient martial arts master, the insane carnage at the House of Blue Leaves, getting buried alive, finally laying eyes on her beloved daughter that she had believed dead—there are so many scenes that could anchor a great film, but Tarantino strings them all together, moving from strength to strength, operating on the assumption that doing so will help overcome the contours of his untamed screenplay.

The Whole Bloody Affair allows these jagged elements and narrative gambles to balance each other, to properly coalesce and compound their effects. Where Vol. 2 once felt slightly hesitant and deflating, its talkiness and melancholy now function as a necessary decrescendo after the operatic chaos of the Crazy 88 sequence that caps Vol. 1. Said sequence, previously in monochrome, is now shown in full color to glorious effect. Elsewhere we find an extension of the anime flashback and the removal of a part one cliffhanger and dozens of others of smaller changes that more studious viewers have compiled into lists; bits of voiceover, a few extra seconds of butchery, et cetera. I still prefer the first half of the movie but the second half massively benefits from being part of a whole instead of a “sequel,” and with the architecture of this combined form, the slower rhythm of the second half no longer has any sense of a letdown but rather of a reset and a reckoning. Even the film’s rampant indulgent sidetrails register less as bloat than as evidence of a filmmaker reveling in the messy fringes of grindhouse cinema and pop culture at large. In that sense, watching this version by myself in a mall theater, mildly irritated by the persistent glow of a nearby cellphone, fueled by the worst possible food, feels oddly appropriate, an embrace of the idea that something ecstatic and joyful and life-affirming can emanate from junk culture. The Whole Bloody Affair perhaps stands as Tarantino’s most persuasive argument that loving trash deeply enough (and of course executing it in the cinema with enough rigor) can transmute it into something that can only be denied on the grounds of personal taste.

If you go to see this in theaters, please do not stick around for the after-credits scene; a gross gimmicky Fortnite tie-in parading as a “lost episode” that actively detracts from an otherwise magnificent experience.