“The numbers are the key to everything.”

Setting an unwitting human character against an inscrutable supernatural force that they are powerless to act against seems like an excellent setup for profound rumination; a platform for asking questions of determination and randomness in the universe. That’s what Knowing is aiming for, but with the smooth edges and shallow characterizations of a run-of-the-mill blockbuster action film, approaching such weighty topics ends up feeling quite silly. Mix in some esoteric red herrings and you’re approaching hokey territory—a recipe for dumb fun, but at odds with the self-serious presentation we’re given here.

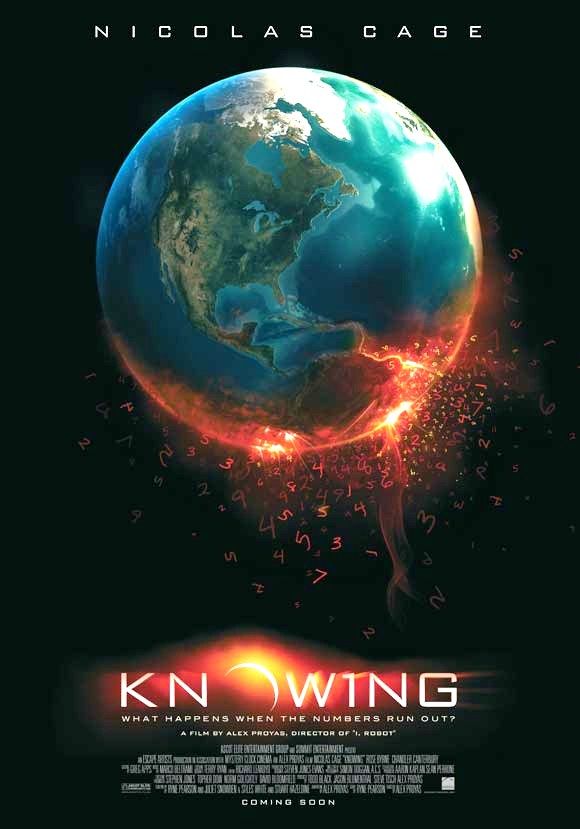

Beginning as an eerie horror film before sidetracking into preposterous sci-fi, Alex Proyas’ apocalyptic thriller has proven divisive on several fronts. One the one hand, it features some terrifically staged supernatural encounters that will send chills down your spine. It also manages to respectfully integrate biblical themes into a story that posits, straight of face, that angels might actually be benevolent aliens. On the other, it treats an outlandish concoction of sci-fi concepts way too earnestly and the typically rangy Nicolas Cage alternates between modes of detached world weariness and freak-out insanity without any in-between. Some (notably Roger Ebert) hailed it as a visionary sci-fi masterpiece while others found too little of substance beneath that alluring façade to connect with. The film definitely has its merits but the loose ends and hollow story push me toward the latter camp. It’s intelligently made by a solid filmmaker, but he’s fighting an uphill battle with the material here.

I think that one’s reaction to Knowing will be heavily influenced how long it takes for them to see through the hokey plot. The film begins with a prelude set in 1959 as the opening of a new elementary school is commemorated by burying a time capsule beneath its front sidewalk. Contained in the vessel are drawings from students depicting their ideas of what the future will look like. As the teacher rounds up the drawings from her students, Lucinda Embry (Lara Robinson) frantically scrawls an unbroken string of numbers down to the very bottom of her page. During the capsule-planting ceremony, Lucinda sneaks into a closet beneath the gymnasium and scratches her fingers bloody etching more numbers into the door. Fifty years later, when John Koestler’s (Cage) hearing-impaired son Caleb (Chandler Canterbury) receives Lucinda’s “drawing” on the fiftieth anniversary of the school’s opening, the widowed astrophysicist puzzles over the numbers, eventually discovering that they predicted the date, geographical coordinates, and number dead of dozens of catastrophes over the past fifty years—and there are three still to come.

After witnessing the first two—a plane crash and a subway train collision, two technically impressive scenes—and realizing that his wife perished in one of the earlier incidents, John becomes convinced that his family is significantly tied to the prophecy. Tracking down Lucinda’s daughter Diana (Rose Byrne) and granddaughter Abby (Lara Robinson), John heads to the prophetess’s childhood home, where he finds similarly clairvoyant material focused on the mystical visions of Ezekiel. He interprets the link to Ezekiel’s vision1 to mean the sun will destroy the earth, and confirms with his MIT colleague (Ben Mendelsohn) that there is a potentially life-threatening solar flare imminent. Instead of trying to take shelter, we’re shuttled back to Lucinda’s trailer in the woods where the mysterious, whispering entities that have stalked our protagonists since the film’s beginning—shooting light from their mouths, evoking visions, standing menacingly in the shadows, and gifting strange black pebbles—reveal themselves to be kindhearted aliens here to rescue humanity by stealing away a chosen few on interstellar arks and starting life anew elsewhere.

Unable to do anything to prevent the disasters but knowing when they’ll occur, John is reduced to a mere spectator of the end of the world. The first hour or so, in which Proyas throws all he’s got into the concept, passably holds up the fiction. But after the subway train fiasco there’s just nothing left to keep our excitement and the ensuing forty minutes or so of padding give us time to think our way through the glossy veneer to the shallow assemblage beneath it. I have a soft spot for Proyas, and I’ll give him credit for making some of these insubstantial scenes glimmer with evocative imagery and dramatic staging. But so many of the events depicted here ignore obvious questions that will arise: why did the aliens, with knowledge of future events, whisper seemingly random numbers into a child’s ear to convey this knowledge? Why convey it at all if the outcomes could not be changed? Why does Caleb write his own list of numbers, if the world’s going to end? Why does John—the first adult to take the numbers seriously—dismiss his own son’s scribblings and not take a look at them? What’s up with the black rocks that the characters find everywhere, and that begin hovering when the arks take off just before the earth is engulfed in flame? In the moment, some of these scenes do an excellent job of creeping up on you and tingling the spine, but there’s really nothing there beyond well-crafted artifice.

Somehow, even though it garbles biblical prophecy and suggests that we’ve mistaken the true nature of what we call angels, it does so without resorting to the denigration of religion. In fact, though it twists scripture for its sci-fi climax, it actually has some deeper Christian allegories. Prophecies are given by outsiders deemed unfit for society, the select few elect are chosen for salvation, etc. John even reconciles himself with his estranged father, the Reverend Koestler (Alan Hopgood), and reaffirms that he believes in the afterlife. I always struggle when Christian allegory like that presented in Knowing is mixed with actual Christian doctrine within the work itself. It almost always feels like an adulteration of scripture. I feel that Proyas and the writers (Ryne Douglas Pearson, Juliet Snowden, Stiles White), for all their faults, at least knew how to stay within the bounds of good taste in this regard. You’re not here for answers but for entertainment. There is no low-brow case made for or against Christianity, and likewise, no secularist suggestion that the end of the world is the result of a manmade cataclysm. In leaving the true nature of the esoteric saviors ambiguous, we’re left with some pondering to do, though the shallow story ultimately undercuts any worthwhile gear-spinning the film may provoke.

In the end, Proyas’ stylish direction cannot elevate us above Cage’s lackadaisical performance, some questionable child acting, and a silly script that devolves under the weight of its pretenses. This had the potential to rival the director’s self-penned Dark City, but the visually stunning ending rings emotionally hollow, rendering Knowing a B movie that takes itself too seriously.

1. “Then I looked, and behold, a whirlwind was coming out of the north, a great cloud with raging fire engulfing itself; and brightness was all around it and radiating out of its midst like the color of amber, out of the midst of the fire.” (Ezekiel 1:4)