“There are no two words in the English language more harmful than ‘good job.’”

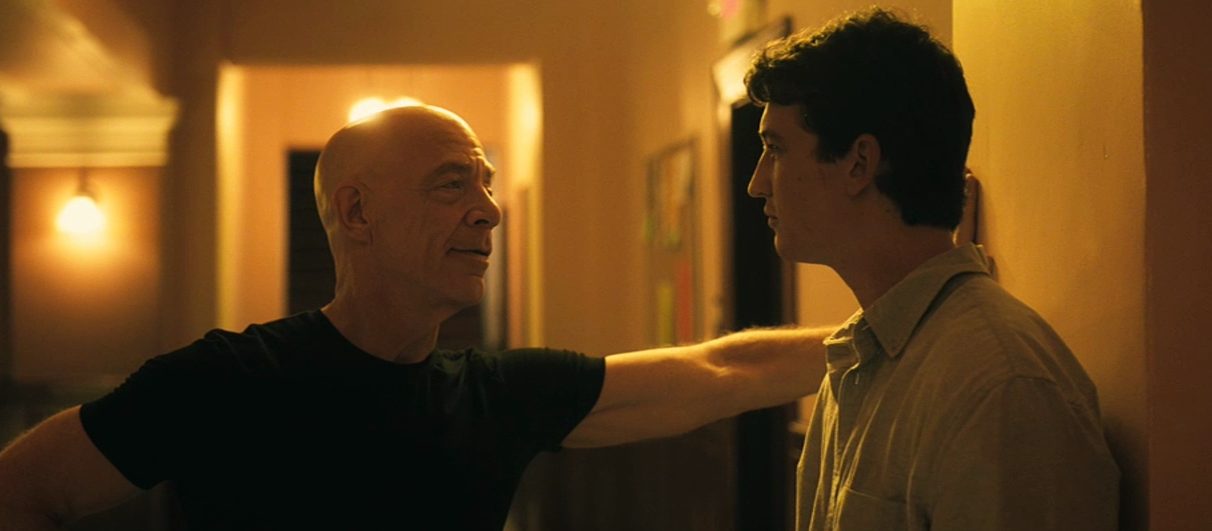

Whiplash, the first major project from director Damien Chazelle after the independent Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, is an invigorating, stylish piece of filmmaking. Inspired by the writer-director’s own time spent in a competitive jazz band, it tells the story of Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller), a first-year student at a prestigious conservatory where infamous hair-trigger sadist bandleader Terence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons) conducts the school’s studio band. One night, Fletcher finds Neiman practicing after hours on campus and invites him to the studio band’s practice the next morning, where he is tasked with flipping pages for the core drummer. Though Fletcher’s uncommonly brutal methods for eliciting perfection (e.g. throwing chairs, slapping faces to demonstrate how to keep time, vulgar insults) quickly result in the shedding of tears, Neiman decides to commit himself to the pursuit of greatness, shortly shedding the proverbial blood and sweat as well. He moves his mattress into a practice room, listens to Buddy Rich non-stop, and practices until his hands blister. There are peripheral threads, like a touch-and-go romance (Melissa Benoist) and a father-son dynamic (Paul Reiser), but this is a thoroughly two-handed affair, with Teller and Simmons carrying the entirety of the drama through to its astounding finale.

Fletcher, who has quickly established a solid position among the most fearsome of modern cinematic villains, builds his motivational techniques around a twisted origin story of saxophonist Charlie Parker, suggesting that his career turning point came when a frustrated Jo Jones threw a cymbal at his head when he flubbed a few chord changes. The takeaway for Fletcher is that genius is not born, but honed through relentless practice and uncompromising coaching. Neiman internalizes this idea, earnestly telling his family at a holiday gathering that he’d rather be remembered for his music and dead at thirty-four (like Charlie Parker) than live a long life and be forgotten. In this way, Whiplash stands in direct opposition to inspirational teacher-pupil films like Dead Poets Society, The Karate Kid, or School of Rock. Even in the film’s finale, which comes after Fletcher’s mystique has been stripped and he’s condensed his coaching philosophy into a convincing monologue, he tells Neiman that he’ll gouge his eyes out. If greatness can only be achieved by sacrificing one’s humanity, is it worth it? Is a world without Charlie Parker’s music a tragedy greater than the loss of a human life to drug addiction at a young age? Either way, at least Charlie Parker experienced the many joys of the musician lifestyle—jam sessions and musical theory and jazz history and camaraderie and so on. The same can’t be said for Neiman, who’s single-minded pursuit of greatness seems entirely driven by pure competitiveness and a desire for affirmation.

Beyond its rich themes, Whiplash must be noted for its cinematic musicality. Audiences (including yours truly) won’t necessarily pick up on the minute characteristics of jazz music that, when not performed with utmost precision, drive Fletcher up a wall, but Chazelle (along with editor Tom Cross and cinematographer Sharone Meir) makes every stray bit of musical performance utterly compelling through sound design, editing, tracking shots, and swish pans. This precise and artful construction puts the viewer in the front row, so to speak. It brings the music to life by accentuating the complexities of the performance and the blood and sweat and spit spilling out of the musicians. Unfortunately, but seemingly intentionally, it never captures the triumphant joy of creating music with other people, suggesting that Neiman’s tunnel-vision pursuit of technical perfection precludes the transcendent elation that often accompanies soulful performance.