“Just because something looks ugly doesn’t mean that it’s morally wrong.”

Lady Bird is a splendidly economical little film. It announces itself without any exposition (its titular main character jumps out of a moving vehicle in the opening scene, leaving her with a broken arm for most of the film’s duration) and doesn’t let up for a minute. Or, on second thought, maybe the whole thing is exposition; a series of thematically linked vignettes pieced together in service of bringing its characters to life and solidifying its sense of time and place. As we momentarily peek into the formative moments of Lady Bird’s late adolescence, we find ourselves almost unconcerned with the resolutions of the few overarching narratives, paying more attention to the interpersonal dynamics and inner changes of our protagonist. The coming-of-age genre is tough to pull off and has many pitfalls, but director Greta Gerwig largely avoids these with this personal drama that has modest aims but thoroughly exceeds them. Although much of what I like about the film is a result of Gerwig’s adept hand, it would not succeed without the stellar performance by Saoirse Ronan as the eponymous Lady Bird. She owns most of the tougher scenes, which range from humor to angst to romance to regret, and knocks the easy stuff out of the park. It’s a milestone for both of them, and was accordingly nominated for a handful of Oscars.

A passing familiarity with Gerwig’s personal history or prior work will tell you that Lady Bird owes its backdrop, if not its intricate details, to the filmmaker’s personal experience. While she is quick to point out in interviews that very little of the film is factually aligned with her own life, some elements—like Catholic school, the love-hate relationship with Sacramento, and the era (early 2000s)—are so ingrained in both that the parallels are impossible to avoid. Similarities aside, it is evident from reading Gerwig’s discussions about the film that Lady Bird is one of those enigmatic characters who somehow took on a life of her own, exerting her irreal will over the writer’s and dictating the flow of her own story; as such, she stands on her own two feet as a singular character of cinema.

“Why won’t you call me Lady Bird? You promised that you would.” Greta Gerwig scrawled this across the top of her working script, which at that point had grown to some 350 pages over the course of several years of off-and-on writing between other projects. It’s a line that Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson (Ronan) delivers to her mother, Marion (Laurie Metcalf); but it also unlocked something in Gerwig’s mind when she wrote it, creating some kind of central focal point that allowed her to wrap the character in flesh in bone, writing and rewriting her story until she had it whittled down to the essentials. Later in the film, as she auditions for her school’s musical, a similar line highlights Lady Bird’s unbridled quirkiness.

Father Leviatch: ‘Lady Bird,’ is that your given name?

Christine McPherson: Yeah.

Father Leviatch: Why is it in quotes?

Christine McPherson: I gave it to myself. It’s given to me by me.

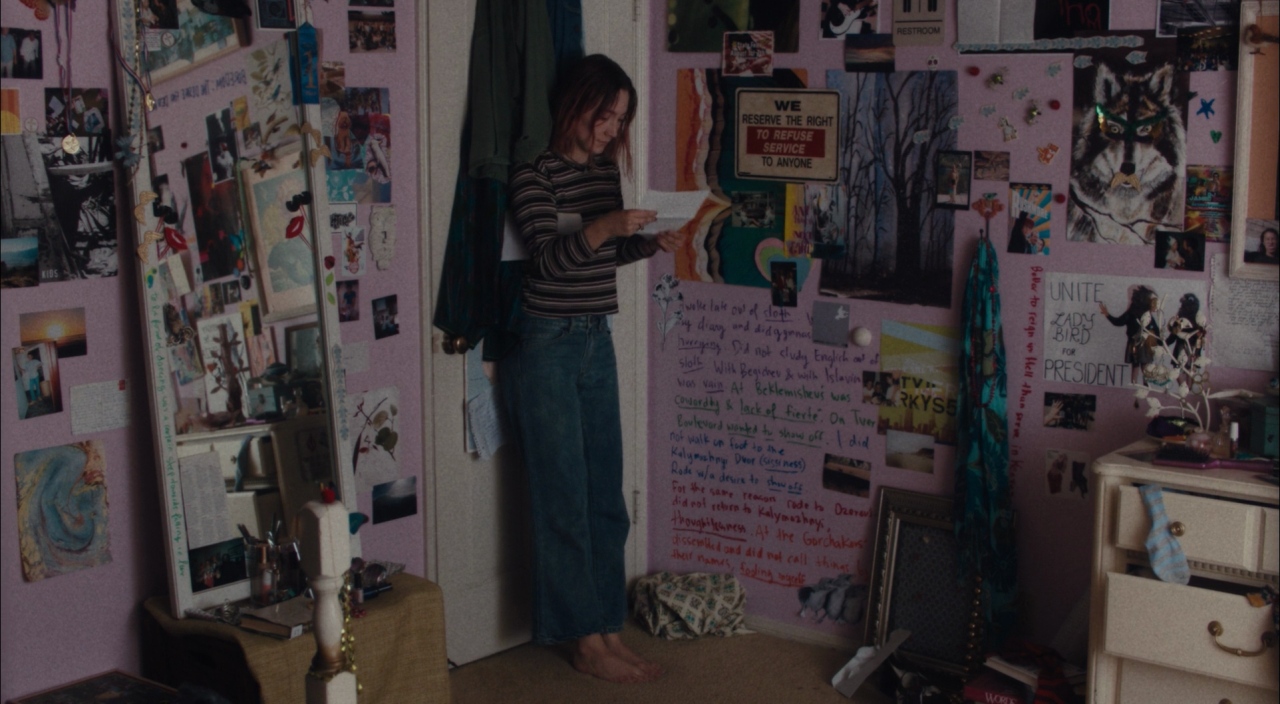

This is a character who eats unconsecrated Communion wafers as a snack food, steals her teacher’s gradebook to avoid flunking, decorates a nun’s car with a sign that says “Just Married to Jesus” and becomes romantically involved with a gay theater boy. She also, after the episode in the bathroom where she finds her boyfriend smooching another boy, falls for the hypocritical neo-Luddite Kyle (Timothée Chalamet) who hates money and thinks people shouldn’t own cell phones because the government uses them to track people, but lives a lavish lifestyle on his parents’ dime. She’s essentially out of control, if only mildly rebellious, making decisions on impulse and then ruminating in angst and regret only momentarily before moving onto the next episode.

At the heart of the film is the relationship between Lady Bird and her mother, Marion (Laurie Metcalf), a woman who struggles with tact, but struggles even more with the unrecognized fact that she doesn’t want her daughter to exceed her modest social status. She works double shifts as a nurse to compensate for her husband’s perpetual stints of unemployment, ashamed of their class and lack of financial means, then shames Lady Bird for wanting better than they have. Their conflict comes to a head when Lady Bird, always dreaming of freedoms and pleasures that only money can buy, demands too much in the wake of her father losing his job. The ensuing confrontation ends with Lady Bird pulling out a notebook and asking her mother for a number—she intends make a boatload of money, write her mother a check to pay for her parents’ “cost of raising her,” then never speak to her again. “I doubt you’ll get that good of a job,” Marion replies.

The pair’s headbutting contests bring out the worst in both of them, but Gerwig deftly leaves room for redemption and reconciliation without letting those moments devolve into sap. The most meaty of Gerwig’s dialogue happens in these exchanges. Perhaps the most memorable occurs when, crowded in the family’s single bathroom with her daughter, Marion admits that Lady Bird’s father Larry (Tracy Letts) has struggled with depression for years.

Marion: Money is not life’s report card.

Lady Bird: He’s depressed about money?

M: Being successful doesn’t mean anything in and of itself. It just means that you’re successful.

LB: Yeah, but then you’re successful.

M: But that doesn’t mean that you’re happy.

LB: But he’s not happy.

It’s been clear since Greta Gerwig began co-writing films she starred in (Hannah Takes the Stairs, Frances Ha) that she was great with dialogue. Where many lesser screenwriters will fill an entire script with drivel to build up to a single pseudo-profound line delivered with dramatic timing and a swell of string music, Gerwig succeeds by giving her characters interesting things to say for the film’s duration. So while Lady Bird struggles into adulthood, applies to East Coast schools behind her mom’s back, and tangles with boys for the first time, we are drawn in by the dozens of individual trivial interactions because they’re interesting and funny in and of themselves.

But the film suffers slightly from the very things that makes it unique. Gerwig came into her own acting in (and writing) films that offered opaque views of individual characters who were brought to life via collaboration between director and actor. While Ronan, Metcalfe and co. do an excellent job of realizing their characters, there doesn’t seem to be much freedom here. This is an exacting script. There is great acting but also great restraint, which can elevate a film to a certain level, but a freedom needs to be granted to the cast to take it beyond that point. The script was so carefully dotted and crossed, the performances so precise, and the pace so breathless, that there is no space for subjective reactions; there’s a lack of ambiguity and breathing room that would have given Lady Bird another layer. And while the film excels as a diverse and piecemeal character study, it nearly squanders everything by trying to corral everything into some grand thesis about the plight of the young and misunderstood, with Gerwig’s screenplay falsifying the character around the time she loses her virginity.

But on net, the sense of authenticity overwhelms these shortcomings. Though it only briefly approaches transcendent greatness for a moment near its ending, there are dozens of individually wonderful short scenes, phenomenally acted, that add up to something of true merit. Gerwig has a very solid handle on the creation of a complete film, and adds a number of nice flourishes by borrowing elements of screwball comedy and montage. Gerwig and Ronan are both rising stars, and though this film is very good, I hope it isn’t the high point of either of their careers.

Sources:

Zuckerman, Esther. “How Greta Gerwig Turned the Personal ‘Lady Bird’ Into a Perfect Movie”. Rolling Stone. 6 November 2017.

Erbland, Kate. “Greta Gerwig Explains How Much of Her Charming Coming-of-Age Film ‘Lady Bird’ Was Inspired By Her Own Youth”. IndieWire. 6 October 2017.