“What is your greatest ambition in life?”

“To become immortal. And then die.”

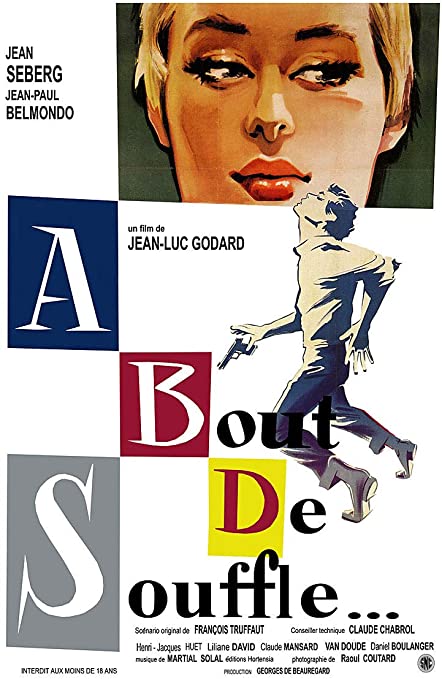

Jean Luc Godard’s Breathless holds a lofty position in the annals of film history. The work of a giddy iconoclast, raised by the cinema and yet intent on reforming it, it was, in its time, an utter departure from the conventions of the medium. Guerilla shoots, jump cuts, alternately headlong and languorous pacing, metatextual homage—so much can be traced back to it that one simply cannot deny its outsized impact on the artform. And yet even so, it is a work that many, myself included, struggle to connect with.

Fascinating but frustrating, it is far less concerned with engaging the viewer on emotional or narrative grounds than underscoring the artifice of cinema, deconstructing narrative storytelling, and exploring the exciting possibilities that the young critic-turned-filmmaker envisioned in its future. There’s a sense of push-and-pull between the director’s high regard for sleek Hollywood entertainment and his unorthodox working methods. Likewise his self-conscious intellectual posturing seems at odds with his intuitive engagement with the act of filmmaking itself. Whereas in later films Godard would work out a rich dialectic between his contradictory impulses—bridging fiction and documentary, criticism and art—here they are pitted against one another almost unconsciously as ideas seem to be arriving faster than they can be incorporated. The result is a film that is jagged and uneven, but one that is refreshing in its unchecked creativity—a premature forerunner that establishes a new template but flounders in its newness.

It is difficult to enjoy Godard’s debut on its own terms, and thus it is astute to approach it from an academic perspective. It is a film to be studied and dissected in classrooms; admirable if not immersive. However, it seems that a lack of audience engagement is part of Godard’s aim. While there’s an inherent charm to the freeform production, like watching a master improvisational musician noodle around, he holds the entire thing at arms’ length with a semi-ironic detachment that renders the entire picture glib. It is as if he is unsure which vestiges of the old way would survive into the future and is thus willing to keep them in his own picture only if he can poke fun at them. And so, though we cannot but acknowledge the impact of its various innovations in tone and technique and structure (there’s a reason the Criterion blurb reads “There was before Breathless, and there was after Breathless”), they are only parts of an otherwise underwhelming film which they are incapable of carrying themselves.

In Breathless, Godard uses his newfangled techniques in service of an improvised homage to classic American gangster films that willfully lacks narrative sophistication and rich characterizations. Indeed, his characters are nothing more than assemblages of pop-culture references and behaviors learned from movies. Early on, Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a reckless young criminal who models his dress and behavior on the hard-edged cinematic personas of Humphrey Bogart, steals a car and shoots a pursuing policeman. One expects this episode to kick off a tense thriller, for Michel to go on the lam and outwit his pursuers. But instead, he just bums around Paris, hiding in plain sight, committing petty theft, calling on his part-time American girlfriend Patricia (Jean Seberg), posturing and soliloquizing beneath the brim of his fedora between puffs on his cigarette. Indeed, it’s decidedly unlike the genre pictures it’s stylistically paying tribute to. This, too, is part of Godard’s schtick. After a while, you come to realize that the director is intentionally avoiding the meat of the story not because he doesn’t know how to make a good movie, but precisely because he does. He understands our conditioned expectations so well that he can’t help but show off his acute understanding of the film-watching experience by subverting them.

But it is in the margins of the story, moments that would have been ruthlessly excised from the script in a classically-arranged film, that Breathless finds its stride. It is here in these quiet spaces that Godard, however infrequently, allows the viewer to connect to the characters in his film—in the pleasant swirl of language, shifting between French and English; in the extended bedroom sequence that finally pierces the self-aware façade and allows the characters to become akin to real through their scattered high brow references.

The challenge, then, is separating the wheat from the chaff—a risky proposition when handling a groundbreaking film like Breathless. One cannot deny the director’s tactical insights, the languid flow of the subversive story, the aesthetic sophistication, and so on and so forth. But is the gangster pastiche worthy? Does every lackadaisical aside that shakes out of the loosely structured narrative work? Not quite. Ultimately, it is the mere act of breaking the rules, rather than the specific choices made here once those rules have been broken, that makes Breathless such a monumental work. Other filmmakers and Godard himself would take the innovations introduced in Breathless and run with them, so much so that a decade later they had become commonplace in Hollywood and are still very much ingrained in the fabric of modern cinema.