“The hopeless dream of being—not seeming, but being. At every waking moment, alert. The gulf between what you are with others and what you are alone. The vertigo and the constant hunger to be exposed, to be seen through, perhaps even wiped out. Every inflection and every gesture a lie, every smile a grimace.”

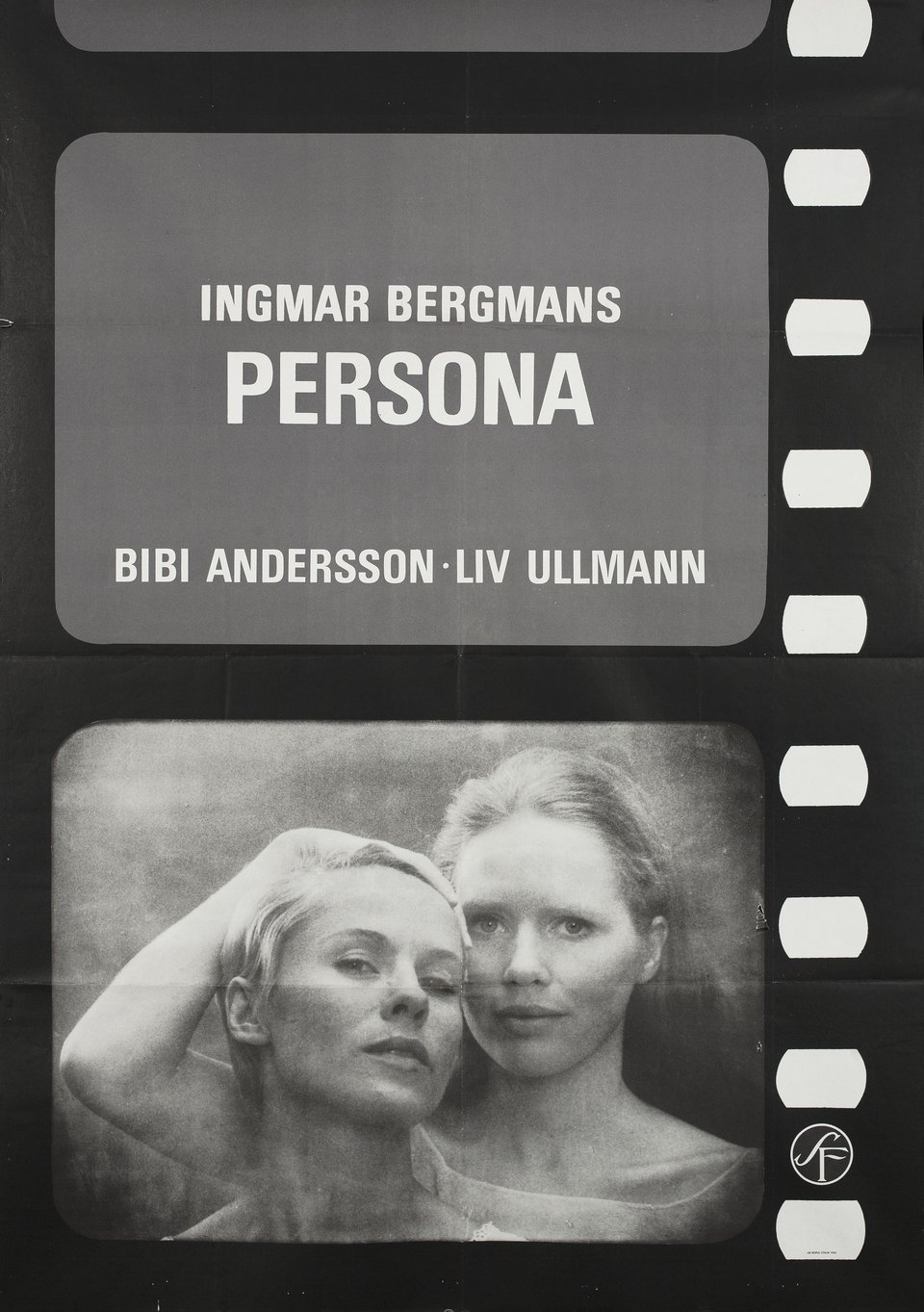

Suffering from double pneumonia, depression, and acute penicillin poisoning, Ingmar Bergman regretfully nixed plans to make a large project called The Cannibals, which was to star Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann. One day while laid up in the hospital, the director was struck by the eerie resemblance between the two actresses when he looked at a photo of them together. Sensing that a smaller film would keep him creatively engaged while he recovered from his illnesses, he began forming a story around a pair of women who gradually lose their identities in one another. But what began as a modest psychological drama quickly grew into one of the esteemed filmmaker’s most experimental efforts; at once both a sublime meditation on the nature of identity and an exploration of the boundaries of the cinematic medium.

It’s easy enough to recommend Persona based only on its technical brilliance, its lush, expressionistic iconography, and its pair of haunting performances. But plenty of films can boast of those characteristics. Few have matched them with a screenplay as puzzling and ripe for analysis as Bergman’s inscrutable curio.

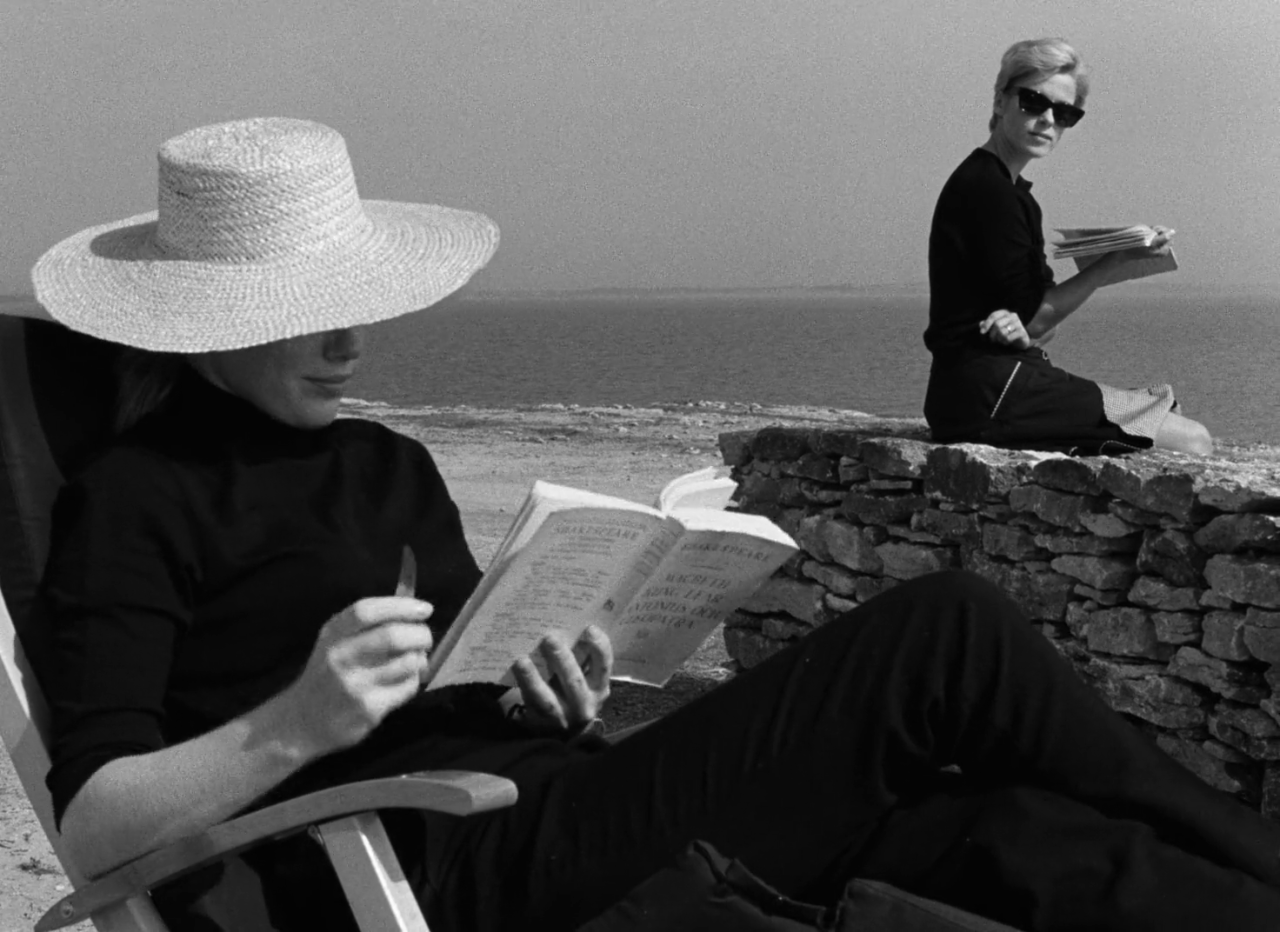

It begins straightforwardly enough. A renowned actress named Elisabet (Ullmann) has withdrawn from her profession and society in general by refusing to communicate via either word or gesture. Her psychiatrist (Margaretha Krook) has determined that her condition is not a symptom of physical or mental illness but of sheer willpower. Alma (Andersson) is assigned as Elisabet’s caretaker and agrees to accompany her when she is transferred from the psych ward to a seaside cottage for rest and recuperation. Isolated from everyone except her charge, Alma falls into a pleasant if one-sided friendship with the actress. She talks and talks about her faith, her family, her ambitions, her failures, her past loves, and finds her new companion a fine stand-in for the sister she’d always wished for. Elisabet, impassive but attentive, appears to be a sympathetic listener, her demure smiles seeming to encourage Alma to divulge her juiciest secrets. One night, after too much to drink, Alma lets her guard down entirely and confesses to cheating on the young man she is dating by impulsively participating in an impromptu orgy with a woman she had recently met and two boys who had been spying on them sunbathing. Her ecstasy was brief, though, and she continues to be plagued by guilt over her infidelity and the abortion that she underwent to terminate the resulting pregnancy.

There is an assumption of confidence between the two women that disappears quickly. The day after recounting her harrowing tale, Alma betrays Elisabet’s privacy by reading her outgoing mail only to discover that she has written about the orgy in violation of Alma’s own trust. This episode more or less destroys the pair’s nascent friendship. Still confined to the premises together, their now-tempestuous relationship escalates into psychological warfare as Alma pulls on every loose thread in Elisabet’s personal life in an effort to cause her emotional torment.

A film of the above description would fit right into Bergman’s overall body of work. And yet that synopsis intentionally leaves out much of what makes Persona such a powerful enigma. For starters, it doesn’t actually begin where I said it began. It kicks off with a montage that features filmmaking elements—a carbon arc projector, a reel of celluloid—and short clips of old cartoons, silent films, spiders, a crucifixion, the slaughter of a lamb, and a three-frame subliminal image of an erect penis (several of these snippets appear to be pulled from Bergman’s previous films). Then a young boy wakes up in a morgue and breaks the fourth wall before contemplating a large, blurry image of two women. Discussions abound on what these images mean, but it is clear that Bergman is making us intentionally aware of the artifice of his film and the medium in general—a stark about face from a director who had been criticized for his indebtedness to the proscenium arch.

After this introduction, however, he plays it straight until Alma decides to pursue revenge. At this point, Persona returns to a self-reflexive mode of storytelling by basically imploding. The projector begins clacking, the image is mutilated, and the reel appears to catch fire. A reversed, looped voice cryptically speaks unintelligible words followed by a few more non-diegetic inserts: a vampire, a skeleton, another crucifixion, an iris. It concludes with an abstractly out of focus shot of Elisabet that freezes her in mid-step for a few seconds before coming into focus. It’s a stupefying sequence that Mike D’Angelo has likened to having a book burst into flames or disintegrate in the middle of reading it.

That moment provides a narrative breaking point beyond which it becomes increasingly difficult to assess the “reality” of the film—which is why it has proven to be endlessly discussable. Maybe Alma and Elisabet are two halves of the same whole. Maybe one exists merely as a figment of the other’s imagination, perhaps as a personal representation of something deeply repressed. Maybe they’re vampires. Or lesbians. Much is suggested as Bergman directs cinematographer Sven Nykvist to linger on closeups of the two leads. At one point, he merges their faces, presenting a startling visage which neither of the actresses recognized as themselves the first time they saw it.

Many critics have taken their turn analyzing various themes and motifs, but I think it is wise to heed Bergman’s own words in his self-penned Images: “For the first time I did not care in the least whether the result would be a commercial success. The gospel according to which one must be comprehensible at all costs, one that had been dinned to me ever since I worked as the lowliest manuscript slave at Svensk Filmindustri, could finally go to hell (which is where it belongs!). Today, I feel that in Persona—and later in Cries and Whispers—I had gone as far as I could go. And that in these two instances, when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover.” In other words, to echo the sentiments of David Lynch (whose masterful Mulholland Drive is clearly indebted to Persona): let the film do the talking.