“Words are more and more pointless. They create misunderstandings.”

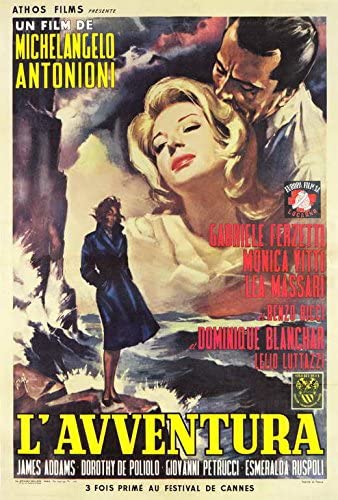

Throughout film history there have been a number of cinematic stepping stones that evolved the artform and ushered in new eras; landmark efforts that have altered the way we conceive of the medium. Many of them enjoy sustained regard and remain unsurpassed, but for others, retrospective discussion must be tempered. Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura is a watershed of the latter type, best understood for its audacity and lasting influence, but not necessarily as a pinnacle of the style it vitalized. Startling in its narrative detachment, it subverts our conventional understanding of cinema as a vehicle for storytelling, offering in its stead an ambiguous mystery without resolution, half-heartedly fumbled through by distracted characters in selfish pursuit of momentary existential relief. A shocking departure from the dramatic norm, using painterly compositions and languorous moments to build a singular poetic vision, it received both jeers and cheers at Cannes, where it was awarded the Special Jury prize “for a new movie language and the beauty of its images.” Today, it’s considered a groundbreaking work. Indeed, its influence has permeated the landscape to such a degree that the challenge in assessing it lies not in acclimating ourselves with the cinematic language, but in perceiving it as novel.

The narrative, such as it were, concerns a group of pecunious Italian hedonists who frolic off on a yachting trip in the Mediterranean. After anchoring near a volcanic island for some exploring, napping, snorkeling, and jigsaw-puzzling, they realize that one of their party, Anna (Lea Massari), has disappeared, vanished without a trace. Dutifully, they scour the craggy nooks and crannies offered by the rocky terrain to no avail. Anna’s father comes to the island, her boyfriend Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) fends off questions of emotional neglect, the police are consulted, a search party cull an inlet for a body. The inconclusive manhunt extends back to the mainland where Sandro seems less interested in finding his missing lover than in pursuing her best friend Claudia (Monica Vitti). They manage to remain chaste for a short time, but each moment that passes without a sign of Anna, their resolve weakens.

On a surface level, the premise is fairly standard, proffering a tried and true formula that could have developed into a standard melodramatic mystery. But this is where Antonioni departs from convention. After winding us up in the film’s first act with the disappearance of Anna, the womanizing Sandro, the morally upright Claudia, etc. he does not follow through on any of the narrative potential offered by those propositions. He is decidedly disinterested in pursuing the missing Anna and so we become resigned to never knowing her fate even as her apparition hangs over her closest friends. In place of a compelling dramatic arc, Antonioni shifts the attention to Claudia’s inner turmoil, approaching concepts much more difficult to convey and less pleasant to grapple with: emotional and spiritual isolation.

As Sandro’s persistence gradually wears at Claudia, L’Avventura becomes a melancholy examination of shallow romance and the malaise that stems from lack of purpose and misplaced sentiments. In their listlessness, Sandro and Claudia briefly kindle a romance, but it is evident that the spark never fully catches even as they walk through the initial paces of a familiar script, feigning concern for morals and reputation all the while. This sense of carelessness—our characters have clearly been afflicted by a modern ill that saps them of both gumption and morals—is perfectly encapsulated in the final scene, in which the almost-lovers spend their first true moment together in the shared realization that they are incapable of knowing one another emotionally, intellectually, physically, spiritually. It’s a sorrowful paradox, a revelation that they are incapable of experiencing real love together. And though the specter of Anna cannot but haunt Sandro and Claudia, it’s at least able to evoke feelings of more or less genuine guilt, an internal pang that has not visited any of her other friends, who simply carry on with their posh gathering and socialite lifestyles.

But it is not through conventional narrative plotting and dialogue that Antonioni evokes this palpable, distressful sense of ennui. In fact, with few exceptions, none of the events in the latter portion of the film are consequential in the slightest. Rather, it is through carefully arrayed, slow-moving images that the director generates meaning, thematic depth, and emotional resonance. In effect, the drawn out visual arrangements tell the story by emphasizing the characters’ senses of loss, alienation, and boredom. Characters are often contained in the frame together but shown facing opposite directions to emphasize their isolation from one another. Trivial conversations and empty loitering are lingered upon to underline a sense of languid detachment.

The island sequence appropriately sets us up for the exercise throughout the rest of the film. In this opening act, Antonioni effectively uses the natural features of the landscape to lure the viewer and the characters into a false sense of merriment. Just like them, we think that some kind of ideal is achieved as the upper crusters head to an idyllic island. But even before Anna’s disappearance the moral and spiritual bankruptcy of the characters is juxtaposed against the natural beauty of the island. Anna herself is mercilessly cruel to her closest friends, and as the story meanders into its middle portion, it becomes lost in a morass of shallow sexual flings. This is most clearly articulated when Claudia wakes up the morning after Anna’s disappearance in a small shack and opens the window to reveal a gorgeous sunrise; she finds nothing in it and quickly turns away with a shiver.

If all that sounds like highfalutin nonsense, well, you have to be at least a little bit pretentious to draw something more than a skin-deep meaning out of a film that’s intentionally devoid of substance. The characters are shallow, the story is threadbare, so we must look beyond them to see what a film made with such obvious intention is trying to say. And when we get down to it, there doesn’t seem to be much there other than a cinematically rendered exploration of restless boredom carried out by dull people—which in turn is, unsurprisingly, somewhat boring for the audience. Still, it must be given credit for its willingness to shirk narrative precision and bombastic storytelling, for opening the door to other filmmakers who would iterate on the patient style displayed here. Whether a great film or not, it’s obviously an important one.