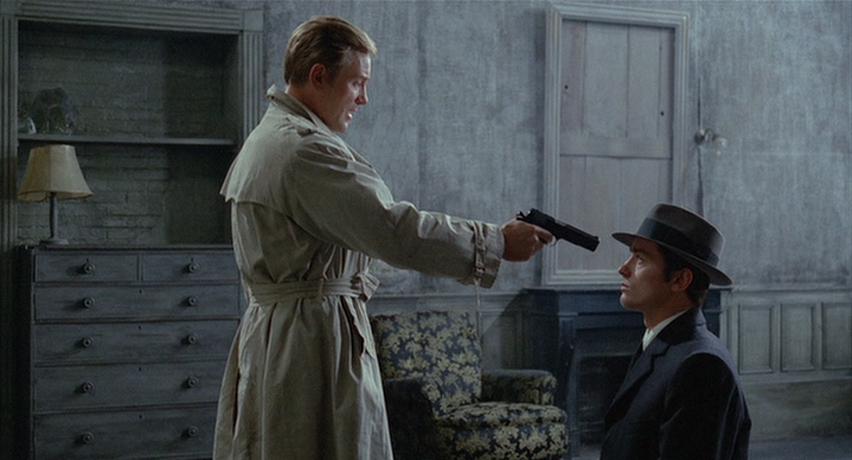

“Nothing to say?”

“Not with a gun on me.”

“Is that a principle?”

“A habit.”

From the opening frame of Le Samouraï, in which Jef Costello (Alain Delon) lies in his bed, fully clothed, cigarette smoke drifting spectrally above him in the bluish grey light of his bedroom, we are given a sense of foreboding. The composition is almost funereal in the way he lies nearly motionless on the bed as the Melville-penned apocrypha attributed to the Book of Bushido informs us: ‘There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai, unless perhaps it be that of the tiger in the jungle.’ At first, we take the assassin’s laconic demeanor to be a byproduct of an indifferent attitude toward the world; a confident composure that manifests as a stoic façade. But behind the handsome face lurks an emotionless killer.

He does not have a line of dialogue until ten minutes into the film. Instead, his actions speak for him. He gestures and expects to be understood, and his actions are taken so precisely and in such a practiced manner, that when he guns down his victim we understand that he has done this many times. He lives by a code, like a samurai, though his code is not imbued with loyalty or honor, but a lone-wolf, survivalist mentality. His life has no real meaning or purpose. He is skilled at his profession, but takes no joy in it. And so we aren’t given a glamorized view of a hitman, but that of an isolated man, stripped of his humanity, enduring a downward spiral toward his own personal eschaton.

Much of what we learn about Jef is communicated visually, as Melville chose to strip the film to the barest elements: sparse dialogue, a muted color palette, and few characters with barely any backstory. Jef’s movements are calculated and calm. He carefully sets an alibi for himself, relying on a prostitute (Delon’s real-life wife, Nathalie) to vouch that he had visited her until the early hours of the morning, and telling his friends that he will join their all-night poker match at 2:00am. After arriving at the nightclub, he shows no emotion as he pulls on a pair of white gloves and walks quickly to the office of the owner that he has been hired to kill.

“Who are you?” the owner asks.

“Doesn’t matter,” the hitman replies.

“What do you want?”

“To kill you.”

As he exits the office, he is seen by the club’s piano player, Valerie (Cathy Rosier). He pauses for a moment, then leaves quickly. He goes through the motions of his alibi, and is playing poker when he is picked up by the police when they search the room during a general sweep and find he fits the description. He is taken in for a police lineup, where he is not identified, though he suspects that Valerie is lying and that she had recognized him. He is let go by the police, but they decide to tail him. As he tries to collect his pay, he is betrayed and injured. He persists through it all with a stone face. Costello remains on the run from the police and the underworld for the rest of the film, with only brief moments of reprieve from the slow burning tension. His nearly animalistic instincts allow him merely to survive one moment to the next.

Le Samouraï illustrates well that using action sparingly leads to a heightened sense of suspense. Although Costello is constantly on the brink of capture, the confrontations are few, and when they happen they are genuinely startling and impactful. For instance, we are given a moment of calm as Costello visits the nightclub, and accompanies Valerie home to question her. The scene is mysterious, as Valerie remains obtuse—telling Jef to telephone her later—but it is also tranquil. As Costello returns to his dingy apartment, which thus far has functioned as a safehouse for him, we are unprepared for the intruder. Due to the dearth of confrontational action, such as shootouts or car chases, the scene has a jarring impact.

At the conclusion of the film, there is a chance for the hitman to make a grandiose statement, as he once again enters the nightclub and dons his white gloves. Instead, the finale is sedate, allowing the film’s aesthetic to remain consistent while giving our anti-hero a chance at a kind of redemption.

Jean-Pierre Melville’s de-glamorization of the gangster is executed well, though it doesn’t always make for immediate enjoyment. The calculated violence of Costello is more realistic than a crime film where the main character goes on a killing spree, sure, but it is more exciting to watch the former. Costello can’t afford to become personally attached to other people, and so we are given very little backstory for any of the other characters. And since he is so guarded himself, we can only infer his state of mind from his actions. This doesn’t make for a terribly engaging story, but it does serve the purpose of casting an unromantic light on the subject.