“I don’t need you to tell me whether I’m cool or not, old lady.”

Paul Thomas Anderson’s best films (I’ll put my cards on the table: Magnolia, There Will Be Blood, Phantom Thread) bear the stamp of his personal filmmaking style—intricate emotional landscapes, sharp insights into human behavior, narratives built from intuition rather than by formula. Alas, when you encourage a creative person to give in to their muse and march to the beat of their own drum, you must take the bad along with the good. Licorice Pizza is, unfortunately, not very good. Which is not to say there aren’t things to like about it, especially for those who are as fervent in their adulation as the cult followers of Lancaster Dodd; I particularly think that centering the film around a pair of first-time actors and allowing them the freedom to discover their onscreen personas was a bold choice that pays off about as well as one could reasonably expect. And his bravura style is intact, if a little dimmed by taking on cinematographer duties himself. It’s just that the willy-nilly, hazy memory plundering Anderson indulges in here doesn’t unearth a masterpiece buried in his psyche, which is what we’ve come to expect from the director.

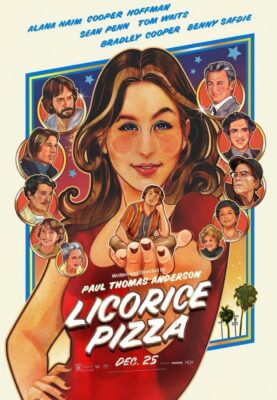

A shaggy, early ‘70s California bildungsroman, the film stars Alana Haim (⅓ of the all-sisters rock band Haim) and Cooper Hoffman (son of departed PTA regular Philip Seymour Hoffman) as a rudderless twenty-something and a precocious, entrepreneurial teenage actor-huckster with miraculously deep pockets for a kid raised by a single mom, respectively, who bounce around a series of slice-of-life vignettes while rubbing shoulders with movie stars and politicians. They sell waterbeds, attend trade shows, mistakenly get arrested for murder, flirt with other potential lovers, get berated by a sex-crazed movie producer (Bradley Cooper), volunteer for political campaigns, open an arcade, and watch Sean Penn do a motorcycle stunt at the behest of Tom Waits.

They also fall in love, of course, or something like that, but (setting aside the age gap that everyone feels the need to call attention to even though pretty much all of PTA’s films are about severely messed up people) the screenplay doesn’t earn the romance it tries to conjure up, too often eliding the crucial moments of the relationship in favor of forced quirkiness and awkward humor and too many shots of our protagonists running euphorically as Hoffman tries his hand at adulthood and Haim pinballs between ‘70s liberation and the solace of a structured adolescence. The film suggests neither would survive this tumultuous phase of their lives without the hope found in one another, but the tender moments simply never materialize. Indeed, the film’s most touching moment is shared not by Haim and Hoffman, but by Haim and Joseph Cross, the secret boyfriend of a local politician (Benny Safdie) who must pose as Haim’s boyfriend to avoid political embarrassment. Maybe in the back of his mind Anderson was a little bit apprehensive about the Harold and Maude angle and didn’t allow the story to unfold as it might have. But he is obstinately committed to the comically tone-deaf Asian accent John Michael Higgins uses when talking to his two Japanese wives, so his rationale for what is appropriate to include is anybody’s guess.

Like Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Licorice Pizza strives to recreate the spirit of a bygone era of the filmmaker’s youth. And while it is obvious that this time capsule holds a great deal of meaning for Anderson and likely others who lived in this place during this time, it is almost laughably trivial to those of us who weren’t there, at least the way it is presented here. It is deeply felt, which usually counts for a lot. It’s also unbearably tedious. Anderson had previously adapted Thomas Pynchon’s meandering Inherent Vice and Licorice Pizza pushes the envelope even further here, barely attempting to connect his loosely-connected scenes to anything resembling a story. I won’t begrudge people their strained whimsicality and absurd prurience (“How big is your penis hole?” Bradley Cooper asks his young co-star. “It’s… regular-sized?” he asks back), and I remain a fan of Anderson’s body of work and remain excited for his projects moving forward, but this one didn’t work for me nearly as well as his other films.