“There’s a difference between lonely and being alone.”

The first character that we encounter in John Carroll Lynch’s Lucky is an ancient tortoise named President Roosevelt. He’s crawling his way slowly across the dry hills of the American Southwest, where the similarly aged Lucky (Harry Dean Stanton) spends his dwindling days wandering between diners, bars, and convenience stores, whittling away at crossword puzzles and watching game shows. He has a rigid routine of yoga, whole milk, coffee, Bloody Marias, and cigarettes—though we never see him eat any real food—and everyone in town knows when and where that routine will take him. Lucky seems like it should be a simple film with its emphasis on banter, trivial arguments, and oddball situations; but all of Lucky’s conversations seem to take a turn toward the existential, gradually building an emotional heaviness until even something as weird as David Lynch trying to will all of his belongings to President Roosevelt has the ring of profundity.

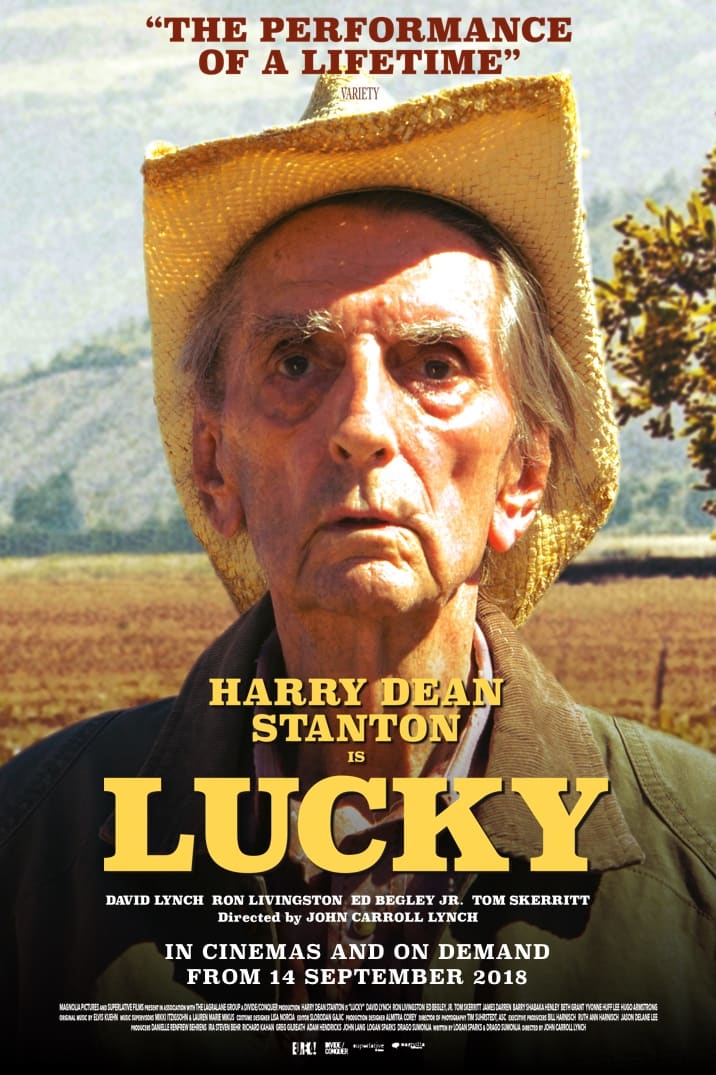

Harry Dean Stanton—who died before the film’s theatrical release—portrays Lucky with a mix of old-man curmudgeonliness and childlike vulnerability as he ponders the end of his life. A career supporting actor (his last starring role before Lucky was Paris, Texas), Stanton became something of an outsider icon for his everyman demeanor, habitual chain-smoking, and refusal to change with the times. There’s perhaps a risk that the tailor-written role of Lucky is too obviously a vehicle for self-mythologizing, but I think this fate is largely avoided by remaining true to Stanton as a person—Lucky is as brusque and unapologetic as Stanton himself, allowing the actor to showcase the persona that he’d solidified over the decades.

Without Stanton’s performance, though, Lucky would not amount to much. Its ruminative narrative arc is so small-scale as to be almost non-existent. The big events are Lucky being hypnotized by the blinking “12:00” on his coffee pot and falling over, smoking weed with a friendly waitress (Yvonne Huff) on his couch while watching archival footage of Liberace, and spontaneously singing “Volver Volver” at a young child’s fiesta. Only the latter truly has the texture of a touching cinematic moment, and it’s probably the best scene of the film. But outside of that, Lucky mostly hinges on its moments of half-serious conversation and introspection. The issue is that rookie screenwriters Logan Sparks and Drago Sumonja try so hard to make their script say something profound that it comes off as amateurish and forced. For instance, while doing the crossword, Lucky gets up from his couch and reads from a dictionary—which he has set up on a podium in his living room. Out loud and to no one but the audience, he recites the two definitions of “realism”—the acceptance of a situation as it really is, and the accurate representation of a person or thing. With this knowledge in mind, he shuffles to the bar where he recites the first definition for all the bar patrons who accommodate his whimsies.

It’s this lack of subtlety that characterizes much of the script, giving it an artificiality that rings partially hollow. It’s not that what is being said isn’t new—it’s clearly not, but such contemplative works have circled around the same themes for eternity—but that it’s so bluntly aiming for something transcendental. None of that seems to matter, though, because Stanton regularly outdoes the material he is given. The scenes are assembled to give him a little bit of everything—the dry adherence to his daily routines, his shirtless confrontation with bodily aging when he faces his sagging body in the mirror, his confession of uncertainty in a moment of vulnerability, his eagerness to engage in fisticuffs with a greedy lawyer, his harmonica-playing, etc. As calculated as they feel, he knocks them out of the park and manages to make Lucky feel like a character distinct from himself, even as so much of Lucky was based on the actor’s life.

Lucky’s acquaintances are an assortment of other character actors—Barry Shabaka Henley as the owner of a diner, Beth Grant as a bar owner, James Darren as her lover and a regular patron, Bertila Damas as a convenience store cashier, Ed Begley Jr. as Lucky’s doctor, Ron Livingston as a lawyer, and Tom Skerritt as a fellow WWII veteran. Each of them is given at least one scene in which they momentarily steal the spotlight from Stanton and give Lucky a solid sense of community. The best of these are Livingston’s recounting of a near-death experience and Skerritt’s verbal portrait of a Japanese girl smiling in the face of death. At first, Lucky is portrayed as a man who is incapable of making friends anymore. Many accommodate his cantankerousness and seem to genuinely care for him, but he prefers to be alone. Eventually, he catches himself by surprise when he finds that he’s strangely attracted to the personalities of others when he realizes that he will lose their companionship when he dies.

It should come as no surprise, but one supporting actor that I’d like to highlight is David Lynch. Lynch directed Stanton a half-dozen or so times as far back as The Cowboy and the Frenchman (1988) and up through Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), in which he reprised his role from Fire Walk with Me. I had sort of expected The Return to be Stanton’s last project, and Lynch gave him a small but weighty role—he plays a trailer park manager who gives a tenant a break on rent when he realizes that the man is selling his own blood to make ends meet, and later cradles a dying child in his arms as the boy’s soul floats out of his body. There’s a thrill in seeing these two friends, legends of outsider cinema, play two old buddies who hang out at the bar and shoot the breeze. Amidst the heavy-handed dialogue, Howard’s (Lynch) self-consciously Lynchian monologue about the lasting friendship of a tortoise stands out as something quite unique.

For a film with such difficult thematic material, there is a surprising amount of optimism pulsing through its veins, but it mostly operates in a mode of quiet desperation. Though the script often fails to convey its points eloquently, John Carroll Lynch does a fine job of capturing Lucky’s more languid moments with grace. The best of these interstitial scenes is when Lucky sits alone on his bed, smoking, while Johnny Cash’s cover of “I See a Darkness” plays. Originally written and recorded by Bonnie “Prince” Billy, who guests on the Cash cover, it was recorded for Cash’s American III: Solitary Man, released a few years before his own death, and makes a similar grasping effort as an old man faced down his own mortality.

Lucky was not widely released. It’s fair to assume that many of the people who saw it and reviewed it probably had a long familiarity with its star, and were thus more affected by it than they would have been had it featured someone else. But to see Lucky look at the camera and tell you he is scared to die is to see Harry Dean Stanton do so. Whether or not you agree with his Zen-like belief, espoused with a smile, that we’ll all be consumed into the void, his existential floundering will tug at your deepest emotions. And it does so without the cheapness of sappy sentimentality. A wonderful tribute to the legendary Harry Dean Stanton.