“Death is listening and will take the first man that screams.”

In Mad Max 2 you could see George Miller intuitively embracing the mythic aspects of the character that he and Mel Gibson had brought to life in Mad Max, transposing the rugged outsider hero from a crumbling dystopia to a post-collapse wasteland for a delirious adventure that concludes with the wandering paladin fading into legend.

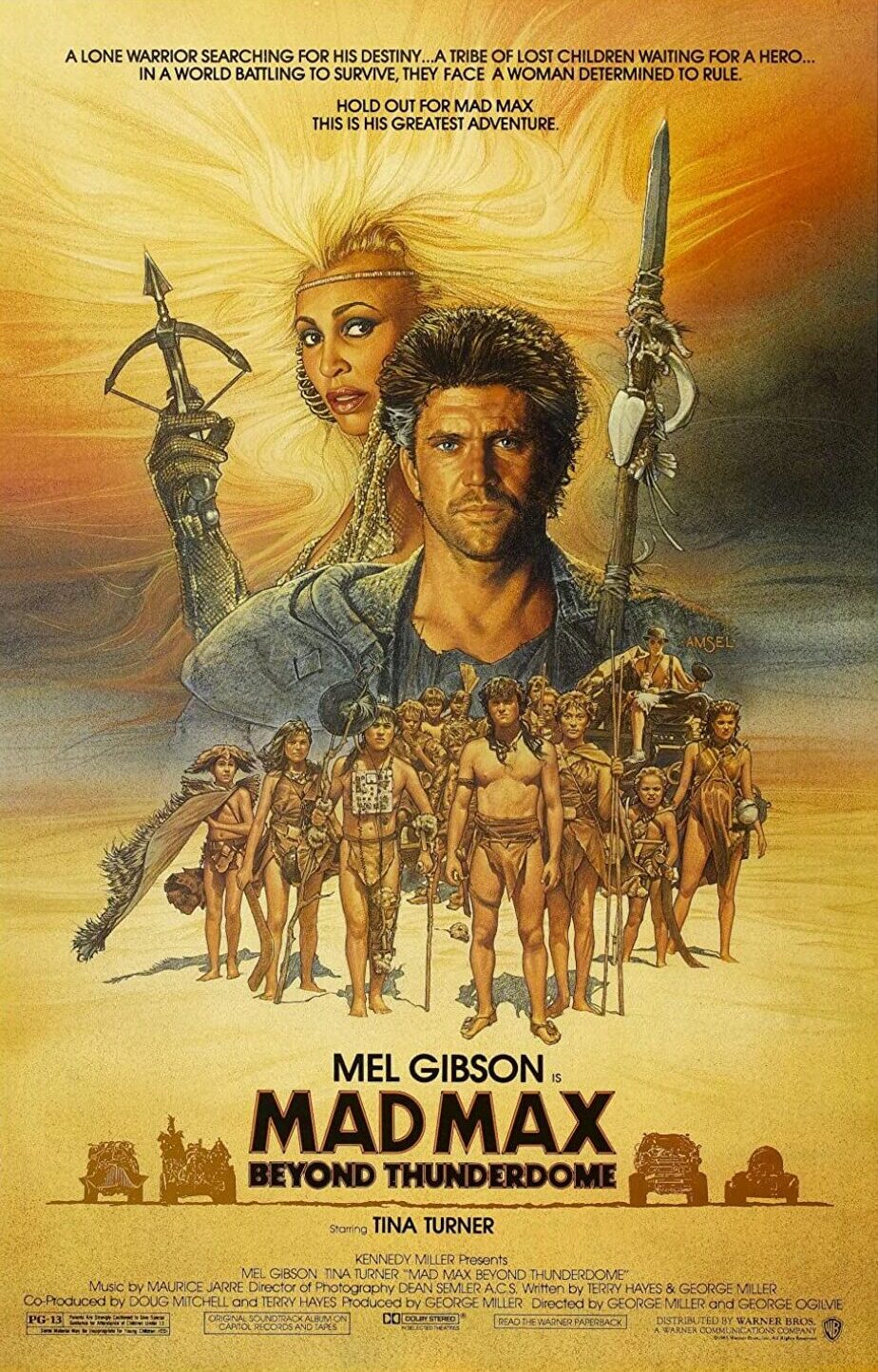

In Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, Gibson’s Max Rockatansky is again the only real connective tissue between installments (and yet even he is not a fixed value), this time drifting into a triptych of reflective story segments that traverse various social environments that emerge after the “pox-eclipse.” The first act finds Max fighting to the death in a domed cage match where both gladiators are bungeed to the ceiling and chainsaws, scythes, and outsized hammers are liberally scattered across the arena, eager spectators hanging from its sides. In the second, exiled from the methane-fueled Bartertown for betraying Aunty (Tina Turner), Max stumbles upon a cargo cult of children huddled up in a verdant grotto, passing down an oral history and waiting for a prophesied savior to rescue them—an interesting, if stilted, take on Peter Pan that doesn’t really fit with the series as a whole.

No longer tied to the pure action cinema of Mad Max 2, Miller (and co-director George Ogilvie) reach for moments of heady epiphany, attempting to link timeless, archetypal bits of lore with the future remnants of our modern culture. They work in zany characters and weird newfangled customs and dubious slapstick right alongside the mythic arc as Gibson’s Mad Max goes through a final transformation, this time emerging as a resourceful, benevolent nomad darkly amused by the strange new world materializing from the ruins of the old one.

And yet, despite all these obvious merits, there is a certain tepidity, a sense of mild deflation, that clings to the procession and prevents it from developing into the riveting piece of cinema it might have been. This is conventionally chalked up to the death of Byron Kennedy—Miller’s longtime friend and producer, who perished in a helicopter accident while scouting locations for the film—or the unfamiliar pressures of studio oversight. Whatever the case, the thoughtfully conceived and brilliantly photographed world of Beyond Thunderdome is undermined by a workmanlike execution that doesn’t stack up to the effervescent passion projects that constitute the first two films in the series.