“I’m not a comedian. I don’t do jokes. I don’t even know what’s funny. I’m a song-and-dance man.”

For Andy Kaufman, life itself was an act. This is clearly illustrated early on in Man on the Moon, Miloš Forman’s biopic of the eccentric entertainer, when a young Andy (Bobby Boriello) is found by his father (Gerry Becker) performing for an audience that consists of little else besides the plaster of his bedroom wall. He was a born performer who followed his intuition wherever it led, without much regard for how his audience would respond to his ideas or if there even was one in the first place. Like Bob Dylan (am I really making this comparison right now?), he was an observer and absorber of culture, and allowed his muse free rein over his impulses.

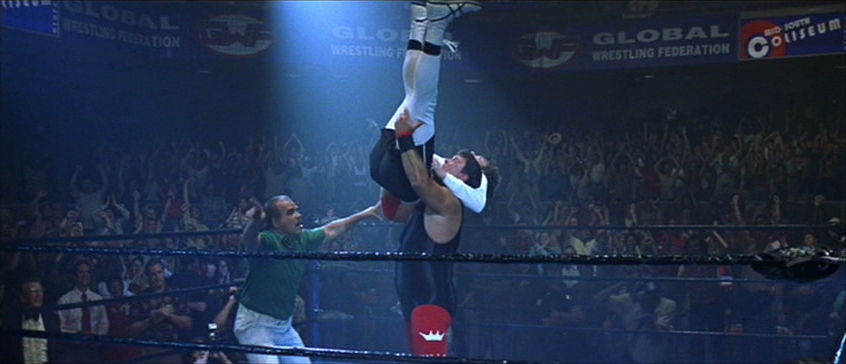

One moment he’s impersonating Elvis, the next he’s body slamming women volunteers from the studio audience, then he’s singing nursery rhymes, then summoning the Rockettes and Santa Clause onto the stage, then going on transcendental meditation retreats and seeking out faith healers. Where Dylan rewrote the American songbook, Kaufman redefined a niche style of performance art, one that erased the line that separates the artist from his art. Even those within his inner orbit could never be sure if his actions were sincere or part of an elaborate gag. At root of this confounding form of comedy was Kaufman’s stubborn ability to drag his jokes through long periods of discomfort, disdain, and pity before finding a cathartic resolution.

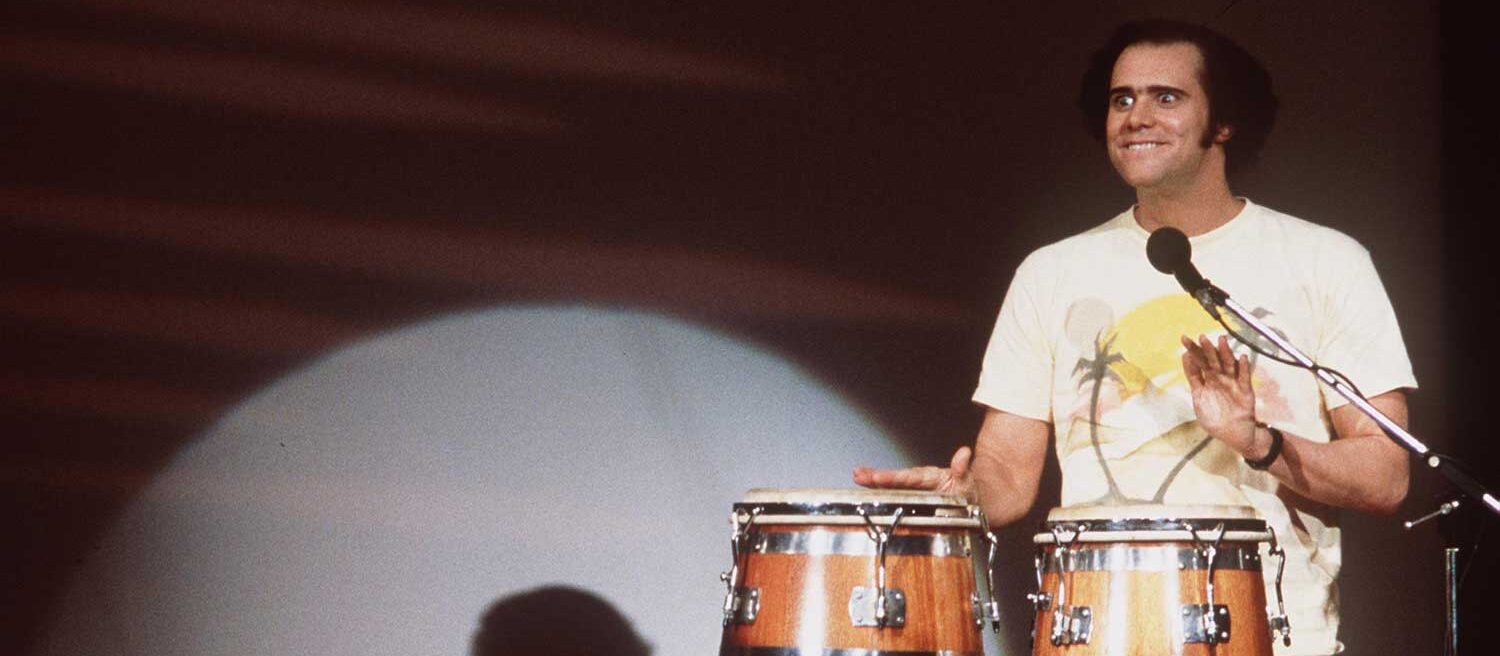

Consider how Kaufman (Jim Carrey) almost blows his big chance by remaining in-character (his “tank you veddy much” Foreign Man persona) when talent manager George Shapiro (Danny DeVito) introduces himself backstage after an odd performance at a small comedy club, only to almost blow it again by remaining totally inscrutable when they discuss business over dinner. Or consider when his collaborator Bob Zmuda (Paul Giamatti)—who’s in on most of the jokes—takes him to a whorehouse to blow off some steam, and the madam informs him that Andy is actually a regular at her establishment; although he usually comes in disguised as Tony Clifton, an abrasive lounge singer alter ego. Or how his planned proposal to girlfriend Lynne Margulies (Courtney Love)—an elaborate gag in and of itself involving a professional wrestling match—is upstaged by a separate, longstanding ruse set in motion by Kaufman and pro wrestler Jerry Lawler (himself) that eventually leads to an infamous slap on David Letterman’s (also himself) late night show. Of course, the tragic granddaddy of them all is that when Kaufman died of a rare form of lung cancer at the age of thirty-five, many suspected that it was all another hoax (the film leaves the possibility open). He had the foresight to record an audiovisual message to be projected over his casket complete with a cheerful singalong, surely he’s just hiding out as a monk in New Mexico and will return at any minute. (Read an excellent piece from Avi Steinberg about Kaufman’s stupefying act and potential resurrection.)

Jim Carrey comes across as a comedic actor inspired by Kaufman in the sense that his most memorable early roles—Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask, Dumb & Dumber, Liar Liar—are spectacles in and of themselves, performed for the actor himself, regardless of how they connect to fellow cast members or the film’s storytelling requirements. He’s a force of nature, a dense center of gravity around which entire films revolve. Such is the case here, only doubly so because Kaufman himself was a similarly magnetic figure and so it’s called for. The film contains a large roster—many actors reprise roles they played alongside Kaufman on ABC sitcom Taxi, others (such as DeVito) took on new roles, while numerous non-actors in Kaufman’s circle appear as themselves or in small parts—but the whole thing is fixated on Kaufman’s non-stop, enigmatic act. Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond, a documentary released in 2017, explores the notion that Carrey was somehow possessed by the spirit of Kaufman during production, leaving cast and crew in a confused and frustrated state.

Rearranging Kaufman’s life story into a series of loosely-connected vignettes for dramatic effect, and breezing past some of his less endearing traits, Man on the Moon is certainly slanted more toward hagiography than biography. But it’s exactly that refusal to try to get inside Kaufman’s head or to dissect his formative years that allows it to come together so beautifully. Reuniting with screenwriting partners Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski (the trio collaborated on The People vs. Larry Flynt), Forman audaciously positions the audience as an audience of Kaufman himself would have viewed him—we are never certain if we’re getting a look behind the curtain or if we’re not witnessing another longform gag. The primary motif here is riffing on that line between Kaufman’s antics and what might be considered his authentic self. The ultimate goal of the film, then—and I think it largely achieves it—is to present that same blurred reality that Kaufman instinctively cultivated around himself. It’s certainly a funny movie, but it’s also unnerving, uncomfortable, and uneasy, just like the anti-comedian’s life’s work.