“My heart bleeds for him, as a child. Someone took a kid and manufactured a monster. At the same time, as an adult, he’s irredeemable. He butchers whole families to pursue trivial fantasies… As an adult, someone should blow the sick fuck out of his socks.”

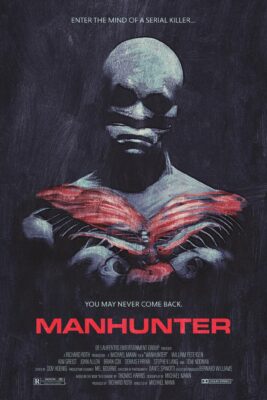

Before Jonathan Demme won all the Oscars, Ridley Scott developed an appetite for brains, or Brett Ratner made his first third-film-in-a-series-that’s-not-as-good-as-the-first-two, Michael Mann introduced the movie-watching public to Hannibal Lecter with the neon-and-forensics crime thriller, Manhunter. Often forgotten as the inaugural adaptation of Thomas Harris’s brilliant, cannibalistic, serial killer—mainly because none of its three primary characterizations (Brian Cox as the incarcerated Lecter, or Lecktor, as the case may be, William Peterson as FBI Agent Will Graham, and Tom Noonan as at-large killer Francis Dollarhyde) are as imposing or iconic as their counterparts in The Silence of the Lambs—Mann’s film is nevertheless a worthy title that fans of the character and other Mann films should be sure to track down.

It follows a similar scenario to the later, more popular film: an agent asks for assistance from an imprisoned Lecter, requesting his intellectual prowess in developing a psychological profile of a killer—this one is dubbed the Tooth Fairy for the teeth marks he leaves on his victims—in order to determine his next move or possibly identify him. Even as it follows a detailed trail of biological evidence and coded messages, the story also delves into the personal traumas of the lead agent—in this case, the fallout from taking on the mindset of a killer one too many times and getting physically assaulted by Lecter; career hazards for the psychic empath that have had a detrimental effect on his own mental health and a severe impact on his wife (Kim Greist) and son (David Seaman).

But (even though I am going to continue to do it) comparing the two films is more amusing than it is fruitful, because Mann’s film is not some wobbly hatchling that needed to grow into something bigger and stronger. It is a fully-formed artistic statement with foremost merits considerably divergent from those of the Demme film; a slow-burn mood piece as reliant on its neon lighting, elegant compositions (Dante Spinotti served as DP), modernist architecture, and pervasive synth score (Michel Rubini, The Reds) as it is on the quiet professionalism showcased in the analysis of fingerprints and hair follicles and toilet paper scrawls.

Though we do get a good deal of angsty rumination from our lead—he’s impossibly torn between his professional and familial duties—and skoshes of camaraderie and compassion between Graham and his boss Jack Crawford (Dennis Farina), the characterizations are uniformly shallow, but charged with emotion. Lecter, in a small but chilling appearance in a max-security prison, is mostly a bored, cocky menace prone to playing head-games. The suspense mainly comes in unfussy bursts of slo-mo action: the mistaken takedown of a midnight jogger, the reporter (Stephen Lang) rolling down the parking garage ramp in flames, the brief, brutal confrontation in Dollarhyde’s exotic lair set to Iron Butterfly’s ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’. Essentially, the agents, victims, and criminals are all elegantly defined symbols in an aesthetic scheme.

An overriding tension is brought to bear that is much more abstract, that comes out of Mann’s hyperreal pillow shots of landscapes, Dov Hoenig’s unusual editing, and the screenplay’s unexpected pivots. Consider that two early sequences consist entirely of Graham investigating crime scenes by himself—a transtemporal voyeur in a one-sided dialogue with his imagined foe as he combs through the living spaces and the woodland surrounding them, extrapolating evidence of massacres to envision the Tooth Fairy’s full-moon slayings in his own mind. These investigations add to Graham’s intel and help form his hunches. They emphasize his anxieties and confusion. But they also suggest that these pristine, expensive homes are extremely vulnerable and inherently alienating. And this is where Mann tends to shine: in the rising action, in the building of psychological tension. In fact, the opening scene, presented in first-person perspective, is one of the film’s best, as an nighttime intruder moves through a home with a flashlight, surveying the children’s toys and other domestic bric-a-brac until finally arriving in the master bedroom where a man and woman lie… dead? sleeping? The woman eventually stirs—one of the last things she’ll ever do—and then we cut to the title card.

After Dollarhyde is revealed for the first time—a shocking cut that settles on the gangly man with a pantyhose obscuring his face—the killer is briefly humanized in the mold of Fritz Lang’s M or Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. At the film lab where he works, he awkwardly flirts with the blind technician (Joan Allen). It’s clear that he’s a social misfit, a slimy recluse accustomed to disregard and contempt and ashamed of his facial deformity. At home we discover he has an unhealthy fixation on William Blake’s series of “Red Dragon” paintings. When fate allows him the opportunity to drive his blind colleague home, he inexplicably takes her to a veterinarian’s office to interact with a sedated tiger (a real, live tiger by the looks of it), feeling its whiskers and fangs and listening to its heartbeat. Even more inexplicable is that she pressures him into sex, after which he silently cries in bed, her limp hand raised to cover his mouth, her unfamiliar touch disturbing to him. The next morning they stand on a dock, silhouetted against the sunrise, and one gets the sense that he might be daring to hope that he could lead a normal life with this woman, that he could ex(or)cise the Red Dragon aspect of himself and just be Francis.

In a late sequence, Graham dreams of one of the victims, only her eyes and mouth have been replaced with pure white—another example of Mann’s bold visuals. These scenes are charged with menace, their meanings multiple and elusive. When we finally charge into the villain’s unholy sanctum, Mann employs a novel “missing frame” style of editing that makes some of the action jittery and jarring. The effect is not entirely successful but it is an interesting stylistic choice.

Some critics dislike that any time at all is spent on Dollarhyde, because the film is about Graham trying to work his way into the mindset of a serial killer, not actually about the killer himself. And while I understand this criticism—which I believe is actually a criticism of the source novel—I think Noonan’s performance is excellent and would actually argue that the movie could be about both things and should have featured more Noonan, who uses his considerable size and gentle demeanor to great effect. I think his depiction of a killer in plain sight is equal to John Carroll Lynch’s in Zodiac.

I would also argue that the overriding, less apparent themes are man’s sense of identity and his capacity for evil. Dollarhyde’s mild humanization gives us insight into the investigator’s mental turmoil and helps us understand the risk he is taking. Graham speaks to himself to help the viewer follow the clues, with the ultimate epiphany that the killer selects his ideal victims while processing their home videos, but unspoken are the excruciating questions eating away at him, such as “Am I capable of the same crimes?”

The surface reading of an early scene in which Graham and his son build rudimentary fences around turtle eggs to protect them from predators is that there is hardly any barrier between these harmonious families and the perverts who would do them harm. But the fences might also symbolize the flimsy mental fortifications that prevent Graham from being overtaken by the psychopathic personas he is investigating. “It’s just you and me now, sport,” he says into his own reflection in a 24/7 diner window. Is he talking to the Tooth Fairy, or his own alter ego, the one that can stay up all night binge watching home videos of dead people?

For these reasons, I find it improper to judge Manhunter against The Silence of the Lambs as if the latter film is a template. I’m tempted instead to compare Manhunter to Dario Argento’s Suspiria, for its extreme color scheme, meticulously composed images, creative expression of spiritual dimensions, and generally unsettling, dreamlike construction. These are both movies that have a few visceral, standout sequences but are largely built upon mood and the threat of violence—the pure power of image, sound, and suggestion produces an experience that is more focused on sensory and psychological experience than narrative storytelling.