“Bad luck isn’t brought by broken mirrors, but by broken minds.”

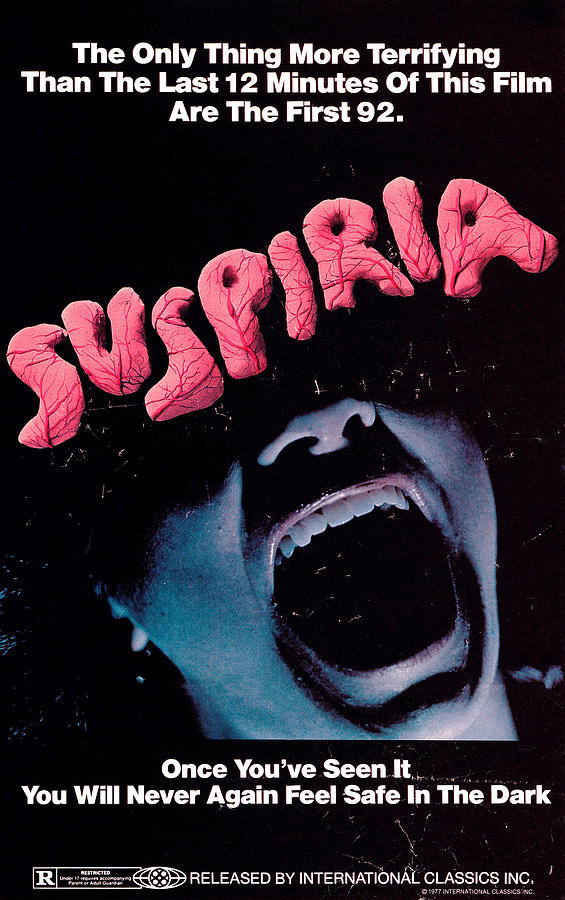

Sometimes I watch so many decent movies in a row that I start to doubt my own taste. I’ll fall into a pessimistic way of thinking where everything seems derivative, devoid of risk and individual style. It’s all rounded off edges and palatable decision-making across the board. I try to convince myself that this stuff is actually really good and that I’m just being a cynic, but I can’t shake the feeling that much of what is pushed on the movie-watching public as art is just as bland and processed as a Twinkie. That may or may not be true, but it takes something special to break me out of that funk—something like Suspiria. A veritable riot of sound, color, and iconic imagery, Dario Argento’s supernatural mystery is a quintessential example of film as a combination of storytelling, music, and image composition. It’s an impossible mixture of visual poetry and shock-horror, glamour and grotesquerie, free flow narrative and stylistic tension. It’s cliché to say it, but nearly every frame could be hung up on the wall. Beyond its captivating visual style, Argento’s dream narrative moves with an unconscious logic, never quite matching up with what the calculating mind expects. His employment of bold color, overbearing music, and time dilation creates a unique hallucinatory aura that is mesmerizing as it works its magic on a non-rational level.

Suspiria wastes no time in transferring you to a different world, one of enchantment, danger, beauty, and superstition. Ballet student Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) is travelling to Germany to begin studying at a prestigious dance school. She is bathed in phase-shifting neon lights during her cab ride through a downpour. The otherworldly nursery rhyme soundtrack from progressive rock act Goblin mingles with the natural sounds of cars and rain, the singers’ violent roars calling our attention to its presence. But without any apparent narrative purpose for the intense music, it encourages us to view her journey as not only physical but spiritual—she is not just traveling to Tanz Dance Akademie, but into the realm of nightmares.

Arriving at 10pm in the pouring rain, Suzy crosses paths with Pat (Eva Axén), a petrified young student who flees the school in terror. Though Suzy remains our central character, for the moment we follow Pat as she seeks lodging at a friend’s apartment in the city. In a long, intense scene, full of highly stylized shots and loud music, Pat and her friend both meet their ends at the hands of a black-gloved demonic force. It’s a shocking introduction, foregoing the conventional period of relative normalcy of a horror film’s first act. At such an early stage, we’re uncertain of Pat’s role in the story; so to see her stabbed repeatedly by an unseen accoster and hanged by the neck from a skylight is staggering. As the bright red, obviously fake blood drips down her body, off her toes, and into a puddle on the floor, the camera pans over to her friend, impaled by debris from the skylight, a piece of glass lodged firmly in her skull. It’s all done with such cinematic bravura and stylistic allure that you simply can’t look away in disgust. Because it’s not disgusting. In fact, it’s almost beautiful, as weird as that sounds.

It’s in this sinister mode that Argento conveys his dark fairytale. He never preys on realistic fears, but rather aims toward enveloping the viewer in mood—a pervasive sense of inescapable terror, every nook and cranny permeated with menace. At the academy, Suzy is introduced to Miss Tanner (Alida Valli), the head instructor, Madame Blanc (Joan Bennett), the headmistress, fellow students Olga (Barbara Magnolfi) and Sarah (Stefania Casini), and a blind piano player named Daniel (Flavio Bucci). In the style of Fellini and other Italian filmmakers, Argento allowed his American, Italian, and German cast members to speak in their native tongues and dubbed which lines needed it for the release in each specific country. This is slightly distracting at first, but once you accept it, it adds another layer to the film’s otherworldliness. The mise-en-scène is also carefully crafted to reflect a sense of the make-believe. The look of Suspiria was inspired by German Expressionism (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu), Disney’s Technicolor animated films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves and Alice in Wonderland, and the works of M.C. Escher. This mixing pot of influences results in unnerving wallpaper patterns, highly unrealistic lighting schemes, and exaggerated architecture—the unusually high doorknobs are frequently cited as a holdover from Argento’s initial draft of the screenplay which concerned girls around twelve years of age rather than twenty.

Soon after Suzy gets settled in at the school, she is subject to a number of strange occurrences. She becomes fatigued during her ballet warmups and faints. Her boarding room is switched while she’s unconscious. The spectral presence of the unseen Helena Markos sleeps near the girls gathered in the gymnasium. One evening, as Suzy combs her hair in dead silence, she discovers a maggot on her comb. Then two more on her desk. She looks up and sees dozens of them clinging to the ceiling. At that moment, out of the silence bursts an intense synth track as pandemonium breaks out across the school and maggots rain from the ceiling. It’s a bold musical moment presented with a charming disregard for convention.

Suzy eventually flounders her way to the bottom of the mystery as more and more of her companions disappear. She speaks with Professor Milius (Rudolf Schündler) who explains the supernatural origins of the dance school and clues her in on a way to defeat the evil that lurks within it. There is a sense of inevitable movement toward the hidden malevolence, but it doesn’t have the clue-finding of a standard murder-mystery and is a far cry from the exploitation slasher style of the director’s earlier giallo films. In fact, many of the film’s most sinister moments are shown to us but kept hidden from Suzy, and she only stumbles her way into the climax at her wit’s end. Even further, many of the occurrences don’t make practical narrative sense, and the characters frequently seem to make odd choices. For instance, when Sarah suspects that the wheezing silhouette sleeping behind the curtain is the supposedly out-of-town headmistress, a quick peek behind the curtain would allow her to verify that. Rather than do that, though, she just frantically whispers her suspicions to Suzy. And when Sarah’s number comes up, she meets her end by jumping into a room that is inexplicably filled with uncoiled spools of razor wire. These “oversights” have no in-film explanation, but that’s just fine.

Argento’s aesthetic approach triumphs because it so thoroughly engages us on a subconscious level. The film is so highly concentrated with visual poetry and musical motifs that intense moments and the actual artfulness of cinema become the focal points, and character and narrative fade into the background. And this is crucial because while there is a fairytale story—complete with witches, potions, spells, etc.—it isn’t an especially engaging one. It lacks the intrigue and intricacy of something like Rosemary’s Baby. But that’s fine, even preferred, because Argento is not looking for narrative tension but a primal paranoia that arises almost involuntarily in the viewer. Too much story detail would muddle that effect. Take the two examples previously discussed. With Helena Markos sleeping behind the curtain, Sarah and Suzy, bathed in red light, frantically converse in hushed tones. Luciano Tovoli’s disembodied POV camera floats over the curtain and lingers on the girls as the soundtrack builds. The tension rises as Sarah’s words cease to carry any meaning for us, the sinister sense of unease rendering the simple act of peeking behind the curtain to verify her suspicions an unfathomable proposition. Likewise, when Sarah is fleeing the dark force, she locks herself in a closet. On paper, Sarah cowering in fear as a straight razor fiddles with the latching mechanism seems trite and uninteresting, but the moment is so overflowing with phantasmagoric stimuli and a palpable sense of danger that we’re enthralled by it. At least I am. It’s such a departure from the norm that I’d expect some to dislike it.

Surprisingly often I find myself locked in an internal debate, struggling to articulate why I dislike so many films for their shaky narratives while also loving the films of David Lynch—which are so slippery that it’s sometimes hard to determine what’s happened at all, let alone if the plot details add up. I find Suspiria to fall into that same peripheral zone, not quite abstract but not driven by story, although its narrative is more intelligible than Lynch’s most abstruse work. I think it’s fair to interrogate the seemingly contradictory stance of liking these oddball films while scoffing at weak stories told in a conventional manner. My position is that Argento is presenting a work that is thematically, symbolically, and tonally unified even though it doesn’t technically “make sense” from a narrative standpoint. It makes “poetic” sense, if you will. (That applies to Lynch too.) The works that I dislike, on the other hand, are so totally reliant on their narrative design for their achievements that when they fail at that, the whole house of cards falls down. Whether or not the lack of a complex central narrative is actually critical to the success of Suspiria is a topic for another afternoon’s pondering. I tend to think additional detail would detract.

So that’s my take on it. You can harp on narrative deficiency all you want, but the pure artistry that takes the place of a robust central story is of such a singular, haunting quality that it evokes a primal response. If you find yourself adrift in a sea of meaningless content, awash in films that all seem to rigidly follow a set of rules, at the very least Suspiria will stand out. But maybe you will enjoy it as much as I did and it will become a new favorite.