“Remember, no matter what, it’s better to be a live dog than a dead lion.”

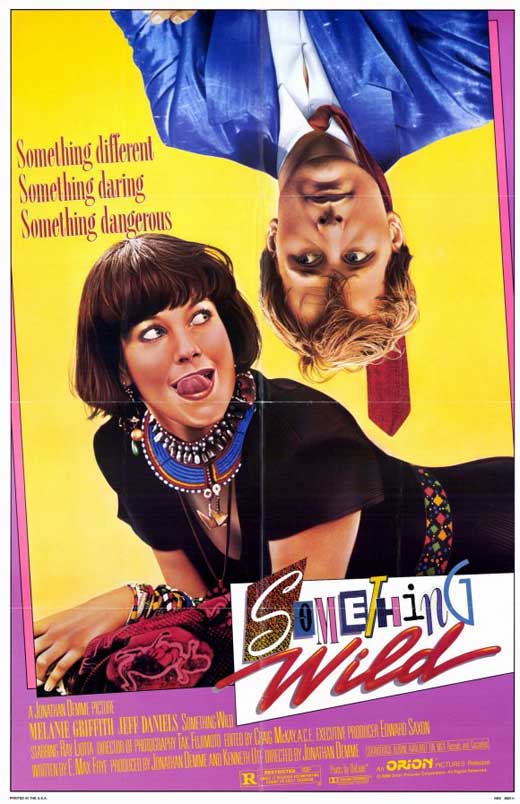

Brimming with eccentric charm and colorful characters, featuring fearless performances from a trio of young aspiring actors, and showcasing the mesmerizing creativite prowess of a confident director at the height of his powers, Something Wild leaves the viewer breathless and invigorated. Careening as it does from erotic screwball comedy to road movie to neo-noir thriller to melancholic drama, it is unsurprising that Jonathan Demme’s undersung masterpiece didn’t gain a foothold in the heart of the mainstream movie watcher. Regrettably, the uncategorizable oddity landed so poorly with the public that it’s often viewed as some idiosyncratic minor work in Demme’s oeuvre and the American canon at large. And yet it’s hard to deny that it was here that the director first figured out how to capture his quirky sensibilities and channel them into an outrageously enjoyable a commercial product.

Jeff Daniels stars as a yuppie NYC tax consultant, an upstanding middle-class dork locked into a world of business jargon and rote office politics. But hidden beneath that wholesome exterior is a mischievous side that catches the eye of Lulu (Melanie Griffith), an impulsive wild child, bedecked with a dimestore wardrobe and sporting a Louise Brooks bob, posing as a waitress at a greasy spoon. She’s not really into personal responsibility and honesty but she sure likes sex and shoplifting. She calls out Mr. Suit-and-Tie Charlie and gets him to admit that he takes perverse pleasure in his little crime of walking out without paying his lunch bill. In that instant a spark is generated, fanned into flame by two wonderful performances. Charlie’s supposed to head right back to the office for an afternoon of important meetings, but something about Lulu’s reckless assertiveness entices him, and a primal curiosity urges him to go along with the whims of this free-spirited character. She, in turn, sees his mild transgression as an act of rebellion against his cultural upbringing; perhaps he is a free spirit too? He’s usually a straight-laced kind of guy who would decline outright, but he accepts Lulu’s offer to drive him back to his office. In short order he has his pager thrown out of the car window, turns a blind eye to a liquor store robbery, uses company money to book a roadside motel room, and finds himself handcuffed to the bed getting his rocks off while a phone is pressed into his ear with his boss on the line asking why he isn’t at the office.

That exuberant episode kicks off a dangerously carefree weekend of sex, booze, happy car crashes, and self-discovery in which Charlie poses as Lulu’s husband when they visit her mother and keeps up the charade as they attend her ten-year high school reunion. It’s at the reunion where Something Wild makes its biggest tonal jump as both Charlie and Lulu—now sporting an entirely new hairstyle and going by her given name, Audrey—run into the last people on earth they want to see. It’s also at this point that the untamed Charlie begins to emerge from the husk of the timid one, and the grounded Audrey begins to emerge from the wild Lulu. Charlie bumps into one of his work colleagues (Jack Gilpin) and Lulu refuses to pretend she doesn’t know Charlie, leaving him to fumble through an explanation about his affair. But trouble enters the picture when the faux-couples’ pretense becomes untenable—Audrey’s estranged husband, Ray (Ray Liotta), turns up at the reunion after his recent release from prison (waltzing into frame in a perfectly-calibrated moment that coincides with a key change in the music and a shift in lighting). The thing is, though, even though Charlie’s been turned on by Audrey’s free-wheeling lifestyle, he’s hilariously oblivious to many of her lies and criminal undertakings, and he completely misses the cues that would indicate that he should avoid Ray. And so he’s entirely unsuspecting of the danger that lies in wait for the lovebirds when they go out for a drink with Ray and Irene (Margaret Colin).

Liotta threatens and probably succeeds at many points in stealing the film from Daniels. He’s a vessel of untamed rage and the sinister charisma on display here must be what landed him the role in Goodfellas. Inexorably but patiently, Demme shifts the tone of the film from fluffy romantic road movie to dark tale of kidnapping, abuse, and deadly revenge. But even as the wounded Charlie must prove to himself that he loves this wild creature that fate has thrust upon him—tracking the reunited husband and wife across the seamy byways of several Northeastern states—even as Demme confidently brings his narrative to a dramatic and legitimately tense endpoint—there’s still plenty of elbow room for myriad quirks and weird diversions that blend seamlessly with the thrilling arc without diminishing it.

To wit, consider the sequence in which Charlie pulls in at a gas station/convenience store across the road from Ray and Audrey. He addresses the attendant, Nelson (ex-Talking Head Steve Scales), by name because he’s wearing a nametag on his work uniform. Nelson likewise calls Charlie by name because he is still wearing his nametag from the reunion. He enters the convenience store, still working with Nelson, who realizes that Charlie is covered in blood from when Ray broke his nose. Seizing an opportunity for profit, Nelson quickly sells Charlie a novelty t-shirt, a hat, shorts, socks, a soda, and a roadmap. But Charlie can’t bear to lose track of his marks, so instead of heading to a restroom, he strips right in the middle of the store as random customers mill about. Nelson, unfazed, gradually picking up on Charlie’s spy game, simply says, “Charlie, attempt to be cool.” It’s heartwarming to see him aid Charlie in his pursuit of self-discovery, even going so far as to restrain from selling him sunglasses because the tacky pair he’d inherited from Lulu already complement his get-up just right. Between his lookout and his changing and his various requests, Charlie approaches the cash register numerous times and in each case he and Nelson both have to duck to see beneath an overhead menu to talk face-to-face. It’s low-key hysterical and ends with the two high-fiving. And yet this extended comedic sequence happens in conjunction with Charlie’s very serious pursuit of Lulu and Ray, just as he realizes he can shed his old identity not just physically, but perhaps psychologically, emotionally, etc.

I’d like to lean into that specific sequence a little more to illustrate just how naturally and exuberantly Demme brings his film to life. The establishing shot includes the gas pumps, the gas prices (69¢/gal!), and the front of the store, and shows Charlie pulling up in his red 1970 Catalina. That’s all that’s required for narrative purposes. But Demme dresses the shot up by nonchalantly including a van towing an antique cannon at the pump opposite Charlie and a circle of four young men swaying in unison outside the store’s front door. Moving across the street where Charlie begins his conversation with Nelson, the sounds of traffic are overtaken by the group of teenage street rappers, bouncing lightly on their feet as they beatbox and trade freestyle rhymes. Once Charlie’s inside, with the muted sound of the rappers still audible, a Civil War reenactor in full regalia checks out and rubs shoulders with him. As Charlie leaves, one of the rappers waves at him to solidify his connection to that magical world that exists beyond the bounds of the film. It’s a blissful two minutes and yet it occurs when Charlie is at his lowest point in the entire film. Truly exceptional stuff, nearly matched by a generous helping of additional colorful side characters played by John Waters, Jim Roche, John Sayles, Sister Carol East, Tracey Walter, Charles Napier, among others.

I would be remiss not to make note of Demme’s eclectic taste and impeccable implementation of music throughout the film. Largely diegetic, from the freestyle rappers to boomboxes to cassette players to cranked-up car radios to a solo harmonica to a singing waitress to a salsa rendition of The Troggs’ ‘Wild Thing’ from the back of a convertible, the soundtrack here is extraordinary, rivaling and maybe surpassing that of George Lucas’ American Graffiti. Demme—along with supervisors Sharon Boyle and Gary Goetzman—pull from a wonderfully diverse selection of musical styles from all over the world—South African mbaqanga, Puerto Rican salsa, Jamaican reggae, Nigerian pop, new wave, punk. The Feelies make an appearance at the reunion, playing some of their own songs along with covers of Bowie and Neil Diamond. Does any other film rival the quantity, diversity, and exquisite implementation of music in Something Wild?

Taut, good-natured, funny, and poignant, Something Wild is a shining example of cinema as as artform. It is endlessly pleasurable from the title card to end credits, jumping around between unexpected beats and offbeats, each more beatific than the last.