“If someone’s wearing a mask, he’s gonna tell you the truth.”

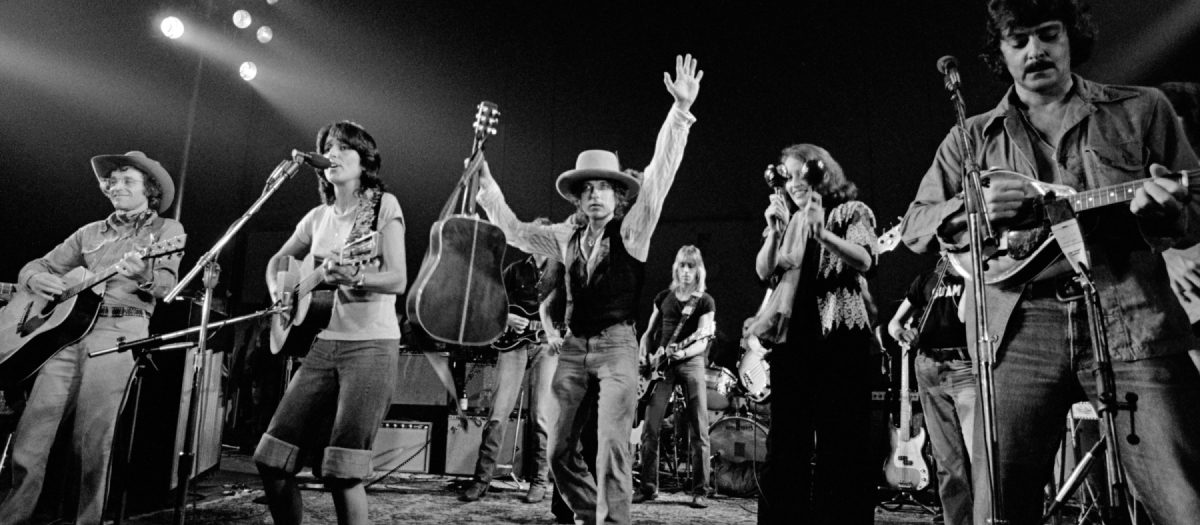

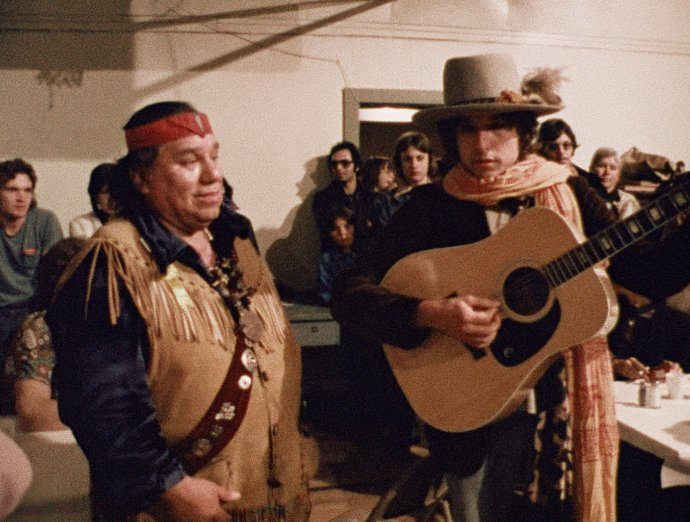

Bob Dylan built a career on subterfuge, mystery, and charisma. When he stopped touring in the 1960s following a motorcycle accident, he sequestered himself in Woodstock to escape public life, write and record—and his reputation as an idiosyncratic recluse began to form. During this time he collaborated with The Band (The Basement Tapes), gospel and country influences began to creep into his music (Nashville Skyline, John Wesley Harding), and he didn’t tour at all; although he appeared at a few benefits and festivals. It wasn’t until 1974 that he hit the road again, playing a month’s worth of huge shows with The Band. But there remained a desire to return to his folk roots, to play personal shows to small crowds and connect with the people. And so after wrapping up the sessions for Desire, he hired a touring band and casually assembled a rotating, come-as-you-please caravan of other, less famous musicians, poets, vagabonds, reporters, groupies, and other creatives—T-Bone Burnett, Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Patti Smith, Phil Ochs, Sam Shepard, Allen Ginsberg, Kinky Friedman, Ronee Blakely, Scarlet Rivera, Joni Mitchell, Robbie Robertson. By all appearances it was a magical time—good music, good friends, good crowds—and the bootlegs from the tour bear that out. From the footage, you can tell that Dylan had a great time fronting his shape-shifting band, playfully jumping around the stage, covered in white face paint and donning a flower-topped fedora, offering new renditions of his most beloved songs as well as soon-to-be classics.

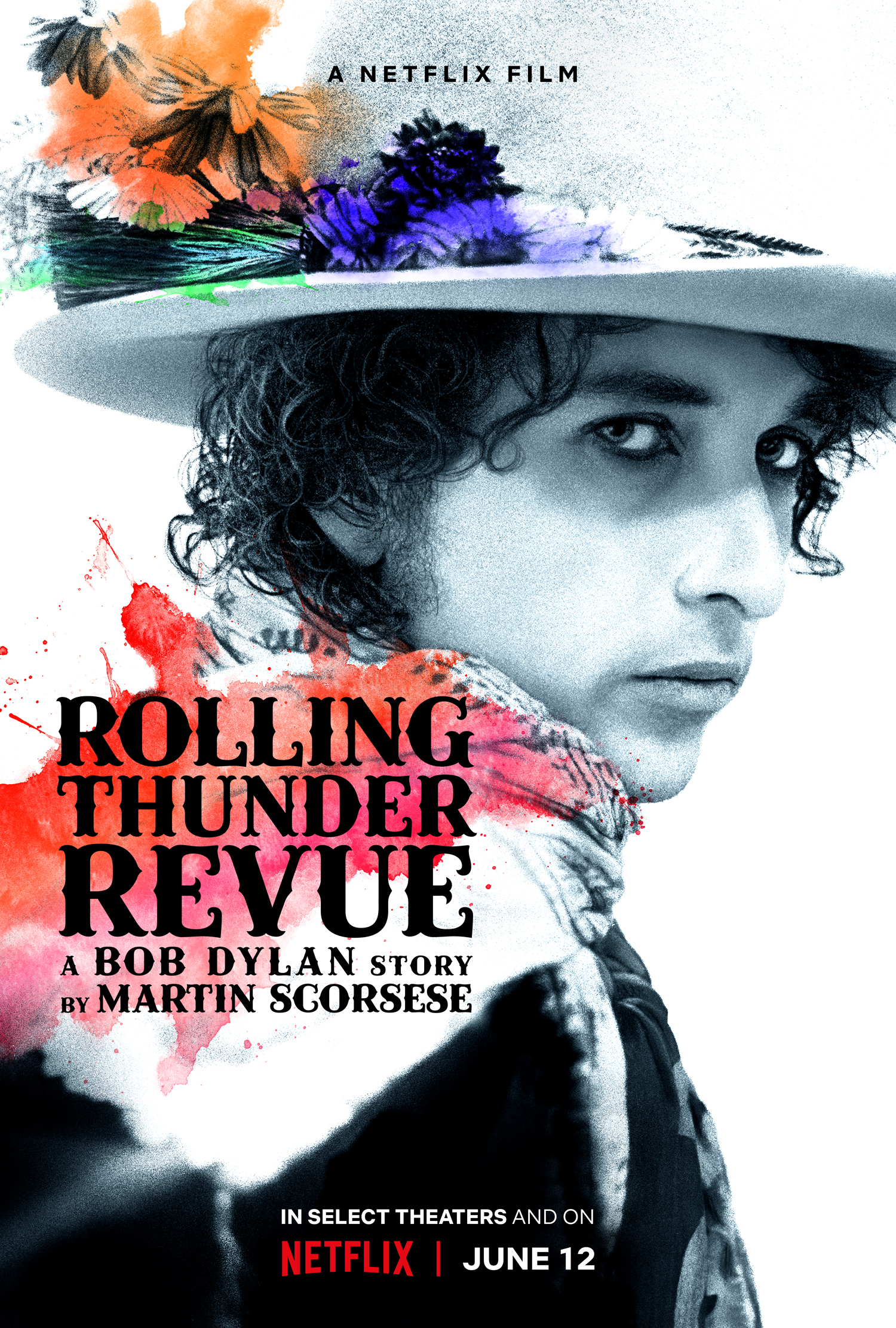

In the midst of this shambolic enterprise of spirited creativity, Bob Dylan decided he wanted to make a movie. Dozens of hours of footage were shot, which Dylan then compiled into the patchy, half-true, pseudo-documentary/mockumentary known as Renaldo & Clara. Although the tour was a critical success, the film was panned and dismissed, and has never seen a home release (though you can find it online if you look hard enough). Enter Martin Scorsese, who had previously contextualized the enigmatic songwriter’s early life and rise to fame, up until the motorcycle accident, in his 3.5 hour documentary No Direction Home. Cobbled together from footage shot for Renaldo & Clara and interstitial present-day interviews, and placed within an abstract framework, Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue is less of a documentary than a second attempt at the slippery mix of fact and fiction that Dylan was aiming for with his 1978 experimental film. Much like the older film, it’s a pretentious and frustrating work, parts of which I love, parts of which I cannot stand. But like its predecessor, too, it’s worth wading through for the performances, at least.

While in theory I am not opposed to the fictional framework, I think it is implemented poorly. If you don’t know that Dylan and Scorsese are being tricksters—hinted at when the film opens with a clip from a Georges Méliès conjuring act—you may be fooled into believing that a European filmmaker named Stefan Van Dorp (Martin Von Haselberg) filmed all of the original footage of the tour, in an attempt to capture “the contrast between the excesses of the people on the tour and the dissolution of society.” He’s pompous and speaks in condescending tones about many of the touring musicians. In reality, the footage was shot by Howard Alk, who had worked on Dylan’s concert documentaries Don’t Look Back and Eat the Document. His fly-on-the-wall aesthetic may not be the most “cinematic,” but it’s really good, and it’s nearly criminal for Scorsese to erase another artist’s work by suggesting a fictional character filmed it all. Likewise, you could be duped into believing that Sharon Stone (star of Scorsese’s Casino), who tells a story of meeting Bob Dylan and being drawn in by his charisma, left her mother after a concert and hopped on the tour bus as a seventeen year old. And again, there’s a story of violinist Scarlet Rivera—an enigmatic figure in her own right, who Dylan literally plucked off the street one day when he saw she was carrying a violin case (and who plays on “Hurricane”). Supposedly Rivera took Dylan to see KISS. Gene Simmons and his pals up on stage in white face paint, with their flickering tongues and drooling blood, apparently inspired Dylan to paint his own face in the Kabuki style. Additional subterfuge stems from the presence of fictional former state representative Jack Tanner (Michael Murphy), the central character is Robert Altman’s mockumentary miniseries Tanner ‘88 and its sequel Tanner on Tanner, who passes along fabricated anecdotes about Jimmy Carter. Because Renaldo & Clara was shot partially as a fictional film, and our trip through the archival footage is not demarcated, we can are never entirely sure if we’re looking at a candidly captured private moment or something improvised but staged. Present-day Dylan offers occasional commentary to muddle things up by referring to fictional characters without a hint of sarcasm. Early on he flatly says that he doesn’t remember the tour at all, but who knows if he’s being honest!

I’m trying to get to the core of what this Rolling Thunder thing is all about. And I don’t have a clue! It’s about nothing. It’s just something that happened 40 years ago… that’s the truth of it.

So you’ve got hundreds of hours of this half-fictional footage, and Scorsese and editors Damian Rodriguez and David Tedeschi chopping and splicing and juxtaposing to their hearts’ content. Unfortunately, this approach undercuts the veracity of the whole work. You’re basically instructed to take nothing at face value. But that’s a disservice to the archival footage—most of which appears legitimate. I’d say at least two-thirds of the film is simply archival material of these nomad musicians as they drove a bus around the country, played shows, and enjoyed the company. There is clearly value in that and plenty of interest for fans of the artists involved, but the fictional frame isn’t a suitable way to present it. So while there are moments that were very satisfying to experience—Patti Smith tentatively leading a crowd in some awful performance art, Joni Mitchell debuting “Coyote” for Dylan, Joan Baez dressing up and imitating him, the visit to Jack Kerouac’s gravesite—they’re all undercut by the jocular framework. This poorly considered choice is even more apparent when there is a serious plight made for the treatment of Native Americans, or when the narrative shifts to focus on Rubin “Hurricane” Carter’s wrongful imprisonment. Those are serious subjects, treated seriously in their individual moments within the film—but juxtaposed with absurd tonal change-ups and satirical interview snippets with the fictional Van Dorp, the message doesn’t feel coherent, considered, or focused at all. It never captures the insouciant attitude of the tour due to its pretentiousness, but also fails to coalesce into anything meaningful, an achievement which would have validated the choice to add all of the fictional elements. The closest it gets to presenting a message is the repeated insertion of Allen Ginsberg’s incoherent semi-poetic Buddhist ramblings, which I can take or leave; though I tend to leave them because I’m not one to take spiritual guidance from such a questionable character.

Let’s take it for the truth that no one remembers the tour, that it’s all just a hazy fever dream, that it has no meaning yada yada yada. There’s still dozens of hours of footage that could have been used to shape this thing into something resembling a veracious account. But the choice to mirror Dylan’s self-contradictory, irrational approach is a detriment to the film as a severe historical document. And it’s simply not that good as a fictional story. Like I said, I don’t hate the framework in theory, but it just doesn’t work out.

But then there’s the performances. For any die-hard Dylan fan, this is still a must-see, because he was great on this tour. This is not the shadowy figure who mumbles his lines and refuses to play instruments that has occasionally reared his head in the past couple decades (though each time I’ve seen him he’s been fantastic) but the energetic, manic, spirited madman who was gung-ho about driving his own tour bus full of vagabonds and putting on a “carnie medicine show” for his most passionate fans. There are a few absolutely sublime cuts on this, though many of them can be found sans video accompaniment on The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5, and all of them can be heard on a massive, 14-disc tie-in box set titled The Rolling Thunder Revue.

Bob Dylan has never been one to present a straightforward version of himself. Even his name isn’t actually his name. In interviews, on the rare occasion that he grants them, he contradicts himself, drifts into poetic spitballing, or openly mocks. His primary talent, outside of his songwriting abilities, is self-mythologizing. It makes sense for Dylan to attempt something like this, or Renaldo, but in my opinion I’m Not There, a fictional film “inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan,” outdoes both of them in the attempt to explore Dylan’s expansive persona. While I didn’t love Rolling Thunder Revue, I appreciated much of the never-before-seen, restored footage of a special moment in time.