“I got poetry in me. But I ain’t gonna put it down on paper. I ain’t no educated man. I got sense enough not to try.”

My first encounter with McCabe & Mrs. Miller came during my college years, a period of discovery during which I became acquainted, however cursorily, with a wide variety of cinematic movements and eras. I particularly enjoyed the films of New Hollywood directors—Scorsese, Coppola, Polanski, Penn, Scott, De Palma, etc.—and did a decent amount of casual reading to get myself caught up and “in the know,” to compensate for years of spontaneous, undiscerning movie watching. I already knew and loved many of these films without knowing anything about the Movie Brats or the Hays code or the studio-bankrupting (eu)catastrophes that marked the movement’s demise, but once I sat through a class on Coppola and saw auteur theory applied to his body of work, I was hooked.

Robert Altman was a director whose filmmaking methods—not to mention his non-conformist attitude—seemed perfectly matched to my tastes. Indeed, as I dipped my toes into his work (I remember seeing M*A*S*H, The Long Goodbye, Nashville, and Gosford Park around this time), his improvisational, ensemble, mic-everyone-in-the-vicinity approach helped bring auteur theory into focus for me. However, I became so caught up in his idiosyncratic filmmaking process that I remained basically ignorant of his penchant for genre subversion (which, of course, also factors into his auteur mystique).

It wasn’t until a friend and I watched McCabe & Mrs. Miller that I was forced to reckon with this deconstructive bent to Altman’s work. It’s simply impossible to avoid. Revisionist Westerns had been around long before Altman put his stamp on the genre, but this is a film so committed to undercutting the Old West mythos that it must be met primarily on those terms or not at all.

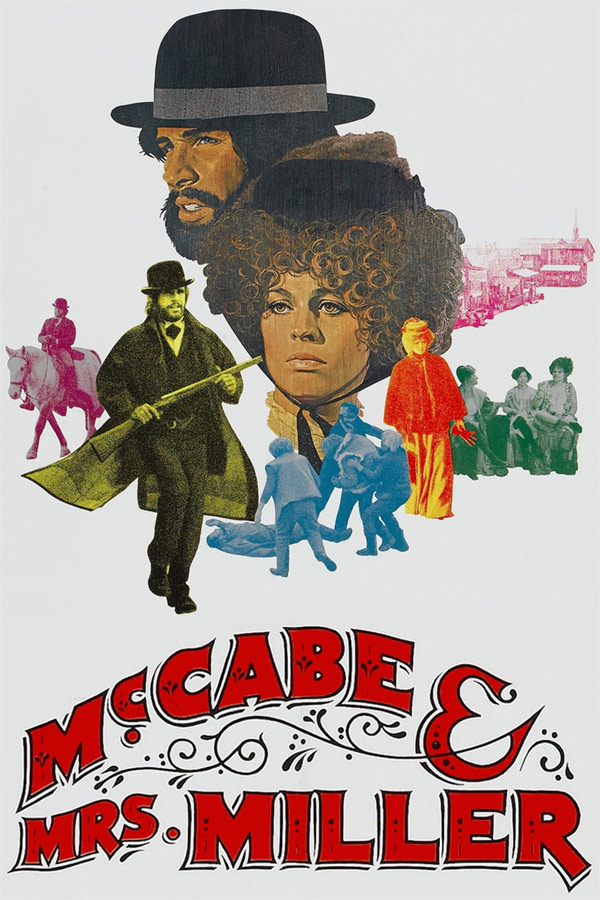

Consider the way that McCabe (Warren Beatty) is initially presented as a charismatic gunslinger—ambling into the settlement town of Presbyterian Church in his bulky fur coat and bowler hat, quickly asserting his dominance over the simple-minded denizens, expanding his makeshift brothel by partnering with the streetwise Mrs. Miller (Julie Christie)—only for time to expose him as an incompetent businessman, a mediocre showman, an ineffectual lover, and bumbling fool who is clumsy with his weapon. Early on he deals cards and smokes cigars at Sheehan’s (René Auberjonois) bar and bluffs his way through business negotiations, but soon finds himself intellectually outmatched by his female partner. Later, after he has refused to sell his business holdings to an interested and notoriously violent party, McCabe crumbles under the scrutiny of a steely-eyed, broad-shouldered outlaw (Hugh Millais) whose looming presence prompts him to talk himself down to a sum barely more than the previously offered amount. But, as McCabe will soon learn, the time for making a deal has passed.

So far you’ve cost me nothing but money. Money and pain. Pain, pain, pain.

Even his demise is stripped of all romance. It occurs during a snowstorm while the townspeople are distracted by the burning chapel, and seems to signify absolutely nothing; neither is it penance, nor some sort of symbolic sacrifice, nor a turning point for the town’s prospects. A read that sees in McCabe’s downfall a subtle condemnation of entrepreneurial pursuits would not be entirely eisegetical, but a plain reading suggests that the point of his death is that people in the Old West died pointless deaths. Such an antihero is a far cry from the virile cowboys that serve as the genre’s archetypal protagonists.

This left field approach suffuses the entire production. On paper the setting is a nascent mining town, so Altman found a suitable spot and had a set gradually erected upon it as filming proceeded, dressing up local carpenters and draft dodging hippies in period attire while they built the town’s skeletal structures—saloons, bakeries, brothels, bathhouses, lodgings—in parallel with the chronological shoot. He even uses an antique steam engine to distinguish Mrs. Miller’s arrival and puts a vintage music box in the whorehouse parlor. As was his wont, he gathered an ensemble and had them make the roles their own through long hours in-character, later using the editing process to emphasize the tangential concerns and flavorful asides of many fringe players that would typically hit the cutting room floor in a streamlined drama.

Traveling lady stay awhile,

Until the night is over.

I’m just a station on your way,

I know I’m not your lover.

Throw in Vilmos Zsigmond’s roving camera, filtered lenses, and flashed negatives, along with the frequent and intrusive use of Leonard Cohen’s music (‘The Stranger Song’, ‘Sisters of Mercy’, ‘Winter Lady’), and you’ve got yourself a heady brew, albeit one that is willfully nonconformant to the expectations one might have of a Hollywood Western. In fact, as Pauline Kael notes in her review, it’s simply “not really much like other movies.” Forgoing traditional introductions and definitions, it portrays its title characters as merely the two most intriguing people in the budding settlement. Others come and go (Shelley Duval, Keith Carradine, and Michael Murphy have small roles, among many others), speak over one another, engage in fisticuffs, have sex, obscure the main narrative, recede into the background. (To be sure, Deadwood owes a great deal to McCabe & Mrs. Miller).

All of this languid commotion creates a revolving door of half-familiar faces that feature in dozens of hazy vignettes that, taken as a rambling whole, amount to an evocative depiction of life in a frontier community that’s heavy on mood and light on beat-driven storytelling. Under the perpetually overcast sky of Presbyterian Church, these heathens toil endlessly, but for what? They are all doomed. The only virtuous man in the film (Bert Remsen) dies senselessly in a street fight. His new bride falls into a life of prostitution to support herself. The tragic young drifter (Carradine) is murdered in cold blood. The reclusive preacher is gutshot in the chapel. McCabe’s corpse stiffens in the falling snow as his sometimes-lover—who required him to pay her usual fee every time he slept with her—gets high in the Chinese opium den. As Ebert remarks, “the film is a poem—an elegy for the dead.”

I’ve come around in the years since I first saw McCabe & Mrs. Miller, seeing intuition, thoughtful rumination, and spirited artistry where I once perceived aimlessness and artifice. It’s a true original, a spellbinding highlight of the American New Wave, an influence on modern masterpieces classics like There Will Be Blood and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and perhaps the quintessential Altman film.