“You mean more to me than any scientific truth.”

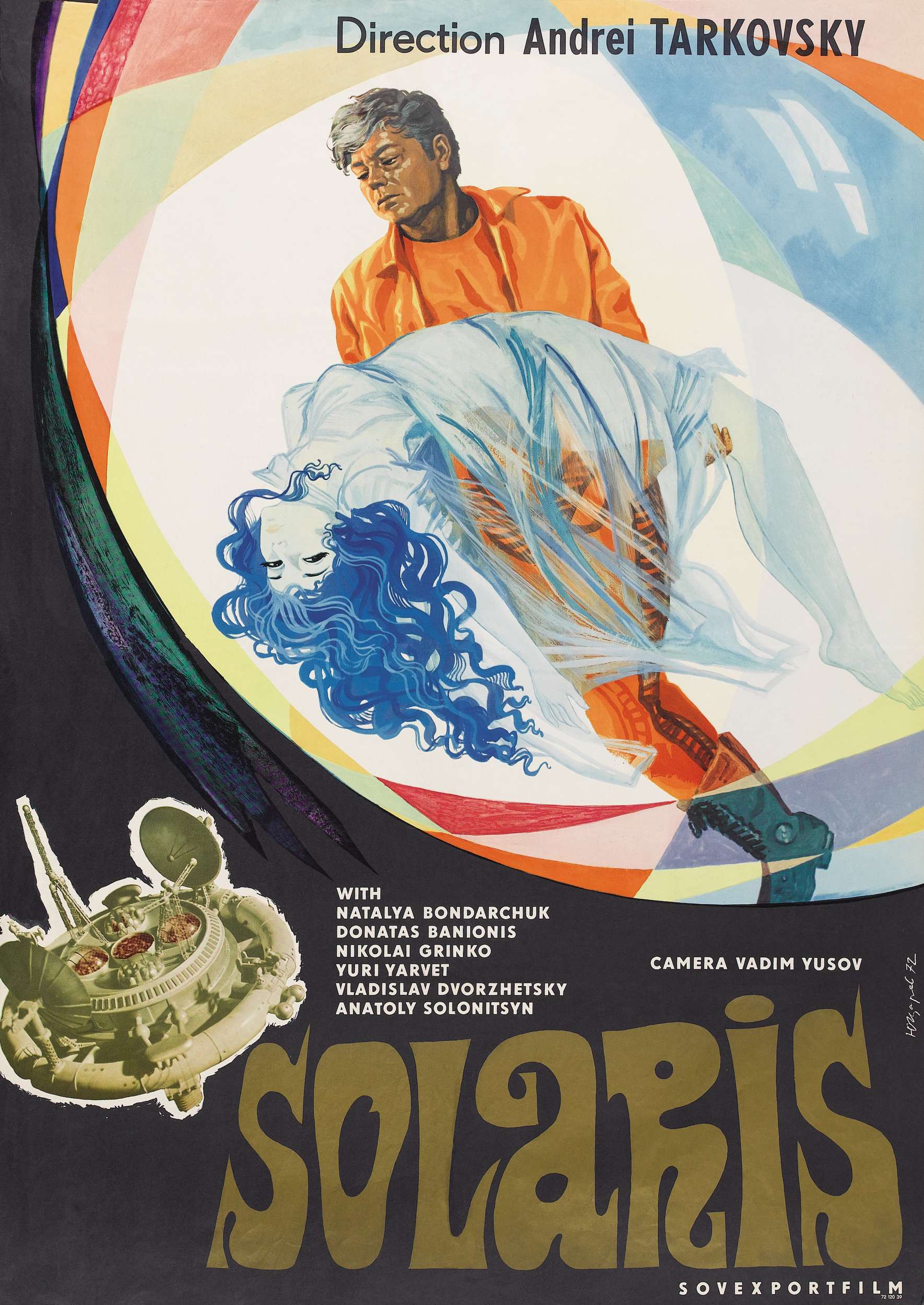

Andrei Tarkovsky was a kind of foreign analog of Stanley Kubrick, seemingly incapable of producing anything resembling a dud despite routinely exploring new genres and ideas. But he never conformed to the standards that would have made his films palatable to a general audience. Instead, he always approached his subjects with a patience and poetic insight that appealed to the cineaste as much as it alienated the layman. Case in point is his 1972 film Solaris, which uses the freedom granted by science fiction to explore the human condition from a novel angle. It’s Tarkovsky’s science fiction film, and yet it stands in contrast to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that Tarkovsky disliked for its emphasis on technical achievement.1 I understand but dislike the constant comparisons between the two because their most superficial similarities are often what is discussed. They may share some tendencies, but their aims are different. 2001 focuses outward where Solaris turns inward; 2001 views the universe through the eyes of man where Solaris looks at man through the lens of the unknown realms of space. Tarkovsky may have crafted his film with Kubrick’s masterpiece hovering over his shoulder, but Solaris is an uncompromising work of art that cared little for convention, comparison, or expectation.

Borrowing the plot from Polish author Stanisław Lem’s 1961 novel, Tarkovsky’s film conveys the personal story of Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis), a psychologist sent to the sentient planet of Solaris. Discovery of the oceanic world had led to new branches of study—careers dedicated to the investigation of the enigma—but after decades of fruitless research aboard the station, the team has been reduced to a skeleton crew. Kelvin’s task is to assess the state of things and determine if the project should continue or be abandoned.

Before he leaves Earth, he spends his last day at his parents farm in the country, visiting them and meeting with a retired cosmonaut named Berton (Vladislav Dvorzhetsky) who, during an exploratory mission years prior, had seen a gigantic child walking on the waves of Solaris, animated by jerky, inhuman motions. This section was one of my favorite portions of the book, and here it is (wisely, I think) conveyed only through words. At the time of the incident, Berton’s claim was contested and ultimately dismissed as a hallucination; but now the remaining crew members are making similar claims.

This lengthy prelude does a great job of setting the tone and the pace for the rest of the film. The dialogue is very contemplative and the editing is very… I don’t know the right word to describe it… serene? sedate? There are many “unnecessary” elements that make Solaris less a piece of entertainment than a meditative experience; e.g. unhurried, lingering takes; shots of plant life, rain splashing into a teacup, slow-moving pond water; a five minute scene that switches between color and black-and-white and is composed of alternating shots of Berton riding in a car and the crowded traffic on the freeway, unadorned with music or conversation. Later, aboard the ship, Kelvin experiences flashbacks from his childhood that center around a wooden swing, a detailed painting, and a small campfire at his parents’ home—none of which have an immediate connection to the plot of the film.

These “boring” moments give us some breathing room and allow the invested viewer to ponder and digest what they’ve seen before moving onto the next scene. This tendency understandably pulls some viewers out of the film, as Hollywood has taught us to expect one entertaining moment to be followed with another. These are not the kind of boring moments that nevertheless convey important exposition—that is to say, they’re not simply scenes that “fall flat.” They’re intentionally slow-moving, meant to draw attention, imbued with meaning yet intentionally left up to interpretation by the viewer. Tarkovsky clearly sees profound significance in the symbolic, but is not pretentious enough to try to explain the meaning of his symbols.

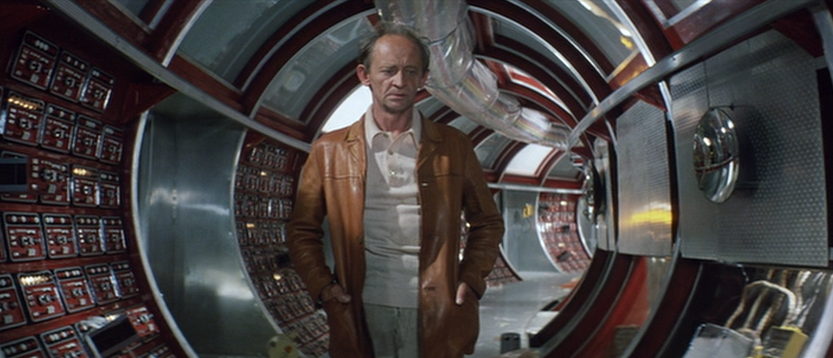

Once Kelvin arrives on the Solaris station, he encounters Drs. Snaut (Jüri Järvet) and Sartorius (Anatoli Solonitsyn)—neither of whom are hospitable in the least—and finds things in a general state of disarray. Kelvin had been anticipating an ally aboard the station, Dr. Gibarian (Sos Sargsyan), but is informed that he has recently taken his own life. As he explores the station, Kelvin catches fleeting glimpses of other people in its curved hallways, and finds a cryptic farewell message left for him by Gibarian.

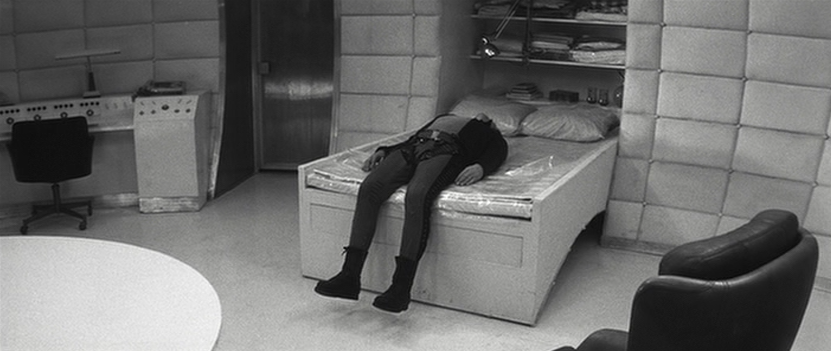

But that’s all a preamble to the real story which begins when Kelvin awakes from his fitful sleep to find his dead wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) in the bedroom with him. Things begin to fall into place now—the child amidst the waves, the visitors Kelvin had seen in his peripheral vision, Snaut’s ragged appearance and mental instability. In a film intent on coloring inside the lines, Kelvin’s aims would turn toward discovering the mechanism by which this flesh and blood hallucination was raised from the grave. But we never really get closer to an answer than postulations—that somehow Solaris has access to their memories. Instead, after launching the first reincarnation of Hari into space on an escape shuttle, only for her to return to his chambers that evening, Kelvin apprehensively accepts her.

But what is she, exactly? She feels, speaks, and acts like Hari—but she’s not Hari, she can’t be Hari. She doesn’t even know how she came to be on the ship. Kelvin discovers that the other two bona fide humans are also hiding memory-creatures in their dorms, but he encourages Hari not to be shy and Sartorius and Snaut gradually, begrudgingly, accept her as well. Nearly paralyzed with his impossible situation, Kris cannot find it within himself to attempt to get rid of her again.

Tarkovsky circles around some big questions about the purpose of life, the bounds of love, and what constitutes a person. Solaris cannot know more about Hari than can be gleaned from Kelvin’s mind, and so the replica that walks and talks and breathes, while indistinguishable from any other person one would encounter, is not human. Can Kelvin really love what is basically only a projection, one that he knows is not the genuine article? (Interestingly, this same issue is gaining some traction in the realm of AI and virtual reality—for instance, consider Spike Jonze’s Her, in which Joaquin Phoenix’s character falls in love with an operating system.)

Snaut: When man is happy, the meaning of life and other eternal themes rarely interest him. These questions should be asked at the end of one’s life.

Kelvin: But we don’t know when life will end. That’s why we’re in such a hurry.

Snaut: Don’t rush. The happiest people are those who are not interested in these cursed questions.

These impossible questions are presented against a backdrop of pure sci-fi. Hari cannot be killed. At one point, she rips her flesh to shreds by tearing through a metal door that separates her from Kelvin, and her wounds heal before he even has a chance to wipe the blood away. Later, when she is reminded that she is not human, and having learned of the fate of the original Hari, she tries to take her own life by drinking liquid oxygen. Devastated by her demise, Kelvin hunches over her body in tears only to witness her flesh magically mend itself. The striking centerpiece of the film occurs when the station enters into an area of zero gravity and Kelvin and Hari and lit candles float weightlessly together.

One element of the film that drew an uncertain reaction from me was the use of dubbing to accommodate foreign actors. Neither Banionis nor Järvet were Russian, so they had to have voice actors deliver their lines from a recording booth. This was not uncommon in earlier eras because filmmakers didn’t have the technology to isolate actors’ voices and achieve a high sound quality. In other cases, like Solaris, or Fellini’s La Strada, multinational collaborations required the non-native speaker to be dubbed by another actor. I think it works fine here, and Tarkovsky’s style is abstract enough that it doesn’t detract from the “realism” very much. However, I also hold the opinion that Bondarchuk’s performance stands head and shoulders above the others, and that may be in part because she was speaking her native language.

In his book Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky made it clear that he disliked the confines of working within a genre. This is curious considering that he helmed two of the most well regarded science fiction films of all time. His statement does not contradict his actions, though, because both of these films (Stalker being the other) are only superficially a part of the sci-fi genre, using a few of its themes and tropes to get at some things more spiritual, philosophical and universal than are typically found mingling with aliens and spaceships.

While this film is rightly analyzed from a symbolic angle—else one risks missing out on its meaning, as elusive as that meaning may be—it’s prudent to avoid overlooking the astonishing visual style that Tarkovsky achieved with Solaris. I think this can easily be overshadowed by his unique pacing, use of black-and-white, and the plot, but the blocking and shot composition are exquisite. One of my favorite visual moments shows Natalya Bondarchuk nearly in silhouette, her features barely distinguishable, as a soft yellow light shines through the checkered squares of her shawl.

Solaris is one of those films whose effect on me I am incapable of corralling into a neat and tidy little summary. Films like Paris, Texas, Days of Heaven, and Chungking Express do something similar for me, slipping outside of the bounds within which I have an ability to break them down intelligently.2 These works differ in many ways, but a common thread links them. Each shrugs off conventional moviemaking techniques with minimal pretension, resulting in true craftsmanship from true artists that were searching for a personal revelation as they made them. Partway through Solaris, Dr. Snaut hypothesizes regarding man’s desire to explore the universe. “We don’t want to conquer space at all,” he says. “We want to expand Earth endlessly. We don’t want other worlds, we want a mirror.” It reads as profound, I think, but I don’t necessarily agree with it. Rather, I think that if we replace the idea of space exploration with “the arts” we can get a lot closer to Tarkovsky’s views on life and the understanding of oneself. In other words, we create things in an effort to understand ourselves.

1. “For some reason, in all the science-fiction films I’ve seen, the filmmakers force the viewer to examine the details of the material structure of the future. More than that, sometimes, like Kubrick, they call their own films premonitions. It’s unbelievable! Let alone that 2001: A Space Odyssey is phony on many points, even for specialists. For a true work of art, the fake must be eliminated.”

2. This is not an exhaustive list, of course. But the others I could name would be similarly diverse in theme, genre, era, etc.

Sources:

Crow, Jonathan. “Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris Shot by Shot: A 22-Minute Breakdown of the Director’s Filmmaking”. Open Culture. 30 June 2015.