“It takes a certain amount of courage, he thought, to face yourself and say with candor, I’m rotten. I’ve done evil and I will again. It was no accident; it emanated from the true, authentic me.”

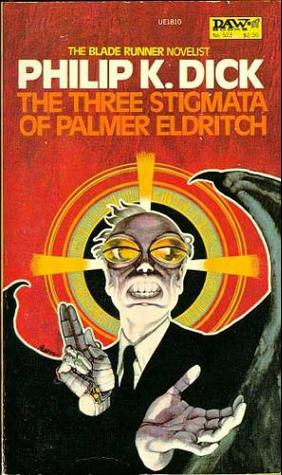

Philip K. Dick’s 1965 Nebula nominee, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, is a zany and outrageous sci-fi romp that considers the interplay between drug-induced hallucinations and religion. With an outlandish and intentionally weird plot, the satirical and humorous novel takes on weighty matters with aplomb.

The story is exaggerated and absurd—visually and tonally akin to something like Luc Besson’s The Fifth Element—but its uneven commentaries on pervasive drug use and religious dogma are apt, if not especially erudite. Of course, Dick is never content to simply present The Idea in his novels—in addition to mind-altering drugs, alternate realities, and new methods of participating in religious rituals, The Three Stigmata also contains technology that allows humans to evolve by enlarging their craniums (they are nicknamed “bubbleheads”), portable psychiatric computer systems that instill mental illness in people so that they are unfit to be drafted as colonists to Mars, and a population of New York City that lives mostly indoors as the surface of the planet is so hot that special cooling gear is required.

In Dick’s gnostic future world, colonists on Mars are addicted to the drug Can-D—a substance which allows them to vicariously experience brief happy-go-lucky episodes in the lives of Perky Pat and Walt, barbie-like dolls which populate “layouts” of upgradeable consumer products that remind the Martian inhabitants of Terra. The communal experience is enhanced by the cohabitation of the two dolls’ bodies—all the women who partake of Can-D in the presence of a layout inhabit the same Perky Pat body, and all the men inhabit Walt, simultaneously. Some of the characters enjoy the experience merely as an escape from their bereft lives on Mars; others make a connection with the “incorruptible bodies” that Saint Paul speaks of in one of his letters to the Corinthians.

The connection between religion and mind-altering substances is prevalent throughout history, though the practice has seen no acceptance in any longstanding Christian bodies outside of the potential similarities between religious euphoria and drug-induced exhilaration. Ancient Greece and Rome both utilized intoxicants in rituals to induce trances, relaxing personal inhibitions and social constraints; the Native American Church claims the entheogen peyote connects them to God; the Rastafarians regard the smoking of cannabis as sacramental; the list goes on.

When Palmer Eldritch returns from a decade long trip to the Prox system, he introduces the colonists to Chew-Z. The new drug isolates its partakers, and allows users to relive their past in ways that may affect the future, and the imagined realities are self-generated rather than confined to the Perky Pat layouts. Once we enter into the realms created by Chew-Z, the book becomes a disorienting and breakneck thrillride, told from a shifting point of view that is ultimately unreliable. The novel’s central characters are, for the most part, cardboard cutouts that exist merely as containers for Dick’s ideas—and so are by and large one dimensional—but this allows the plot to jump around without aggravating the reader too much for neglecting any single character. Its style is similar to Dick’s other 1965 Nebula Award nominee, Dr. Bloodmoney, or How We Got Along After the Bomb. (Both of Dick’s novels lost to Frank Herbert’s matchless Dune.)

Barney Mayerson—as close as we’ll get to a protagonist—is a precognitive consultant for P.P. Layouts, the creators of the Perky Pat spreads that the users of Can-D utilize for their communal trances. Dr. Smile is Mayerson’s portable computerized psychiatrist, responsible for conditioning him to be unfit for life on Mars. Mayerson’s boss, Leo Bulero, is an evolved human (“bubblehead”), desperate to protect his monopoly on the drug trade of the colonies. Mayerson is seeing a ruthless and manipulative precog named Rondinella Fugate, who wants Mayerson’s job, and then Bulero’s job. Richard Hnatt is a salesman of his wife Emily’s pottery—products which are miniaturized and used in the Perky Pat layouts. Anne Hawthorne is a willful migrant to Mars, anxious to evangelize the drug-addicted colonists for the Reformed Branch of the Neo-American Church.

Anne’s brief sections of the novel are amusing, if only as a display of Dick’s wide-ranging knowledge. He comments on the issue of Apostolic succession, and makes reference to Augustine’s Confessions and The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, and even quotes from Thomas à Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ (which I was coincidentally reading at the same time as The Three Stigmata). Mayerson likens the consumption and subsequent translation of Can-D to the consumption of the Eucharist, a suggestion which is also made by Dr. Denkmal, the therapist who oversees the clinic where evolution, and sometimes accidental devolution, takes place.

You’ll have many new and exciting concepts occur to you, especially of a religious nature. Oh, if only Luther and Erasmus were alive today; their controversies could be solved so easily now, by means of E Therapy. Both would see the truth, as zum Beiszspiel regard transubstantiation—you know, the Blut und—” He interrupted himself with a cough. “In English, blood and wafer; you know, in the Mass. Is very much like the takers of Can-D; have you noticed that affinity?”

The last third of the novel is completely off the wall, as we jump in and out of drug-induced virtual realities like Inception, but without a perpetually spinning top to tell us we are still in an alternate reality. Dick’s straightforward and decidedly unpoetic prose is remarkably effective at disorienting the reader, as well as inducing unease. When Leo takes Chew-Z for the first time, he is able to control the reality around him, and his capabilities horrify him.

[…] not looking at Miss Fugate he said to himself, You’re my age, Miss Fugate. In fact older. Let’s see; you’re about ninety-two, now. In this world, anyhow; you’ve aged, here…time has rolled forward for you because you turned me down and I don’t like being turned down. In fact, he said to himself, you’re over one hundred years old, withered, juiceless, without teeth and eyes. A thing.Behind him he heard a dry, rasping sound, an intake of breath. And a wavering, shrill voice, like the cry of a frightened bird. “Oh, Mr. Bulero—”

[…] He turned, and saw Roni Fugate or at least something standing there where she had last stood. A spider web, gray fungoid strands wrapped one around another to form a brittle column that swayed… he saw the head, sunken at the cheeks, with eyes like dead spots of soft, inert white slime that leaked out gummy, slow-moving tears, eyes that tried to appeal but could not because they could not make out where he was. […]It was not Roni Fugate who stood there, not even an ancient manifestation of her; it was a puddle, but not of water. The puddle was alive and in it bits of sharp, jagged gray splinters swam.The thick, oozing material of the puddle flowed gradually outward, then shuddered, and retracted into itself; in the center the fragments of hard gray matter swam together, and cohered into a roughly shaped ball with tangled, matted strands of hair floating at its crown. Vague eyesockets, empty, formed; it was becoming a skull, but of some life-formation to come: his unconscious desire for her to experience evolution in its horrific aspect had conjured this monstrosity into being.

The jaw clacked, opening and shutting as if jerked by wicked, deeply imbedded wires; drifting here and there in the fluid of the puddle it croaked.

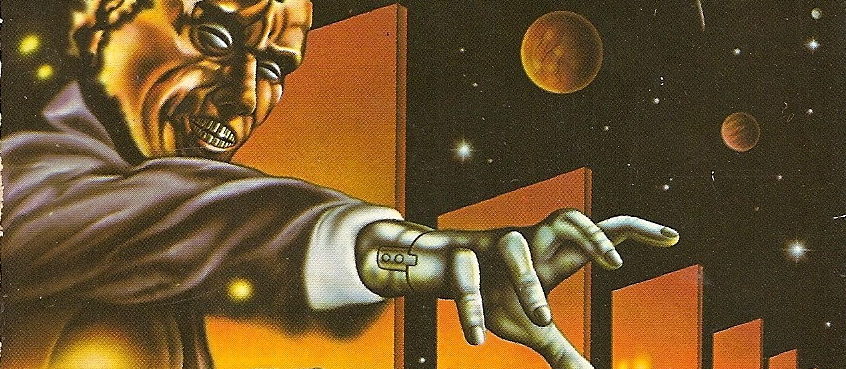

The underdeveloped characters allow for unpredictability, and the curveballs fall in evermore rapid succession as the novel comes to a close. Palmer Eldritch may be as ubiquitous as the titular substance of Dick’s existentially nightmarish Ubik, or he may have been replaced by a malevolent alien entity. Eldritch’s three stigmata—stainless steel teeth, a mechanical arm, and electronic eyes—begin showing through the insubstantial bodies of the characters in each reality and each timeline, until the novel abruptly ends, each character now potentially a cyborg.

From a structural standpoint, the novel is probably too spread out, with its many undercooked throwaway plotlines included only for their novelty. The lack of a clear hero makes the novel interestingly not a battle of good vs. evil, as even Palmer Eldritch (or the alien life form that replaced him) seems more unknowable than clearly evil. And the ancient being is so unintelligible by our main characters that the atheist Mayerson must resort to God as its closest comparison. But Anne Hawthorne rejects Mayerson’s characterization.

The key word happens to be is. Don’t tell us, Barney, that whatever entered Palmer Eldritch is God, because you don’t know that much about Him; no one can. But that living entity from intersystem space may, like us, be shaped in His image. A way He selected of showing Himself to us. If the map is not the territory, the pot is not the potter. So don’t talk ontology, Barney; don’t say is.”

Dick’s bold ideas about God, religious experience, and drug use, and his general paranoia about the reality of his own experience result in a bizarre and mind-bending novel that is chock full of ideas—probably too many, in fact. That the author is unwilling to spoon feed his audience (if only because he himself did not have any answers) gives the reader a lot to chew on, but I’m unsure if my experience has left me any more of a bubblehead than I was before.