“I taught some of the stupidest children God ever put on the face of this earth and all of them could read well enough to find a name on a tombstone.”

Driving Miss Daisy touches on some important issues—namely, racism, anti-Semitism, classism, and ageism. There might be a few more -isms that I missed. I don’t want to discount those elements, but it is clear that the film’s success rests not on the depth of its political commentary or on its cinematic merits but on its thoughtful screenplay and pair of lead performances.

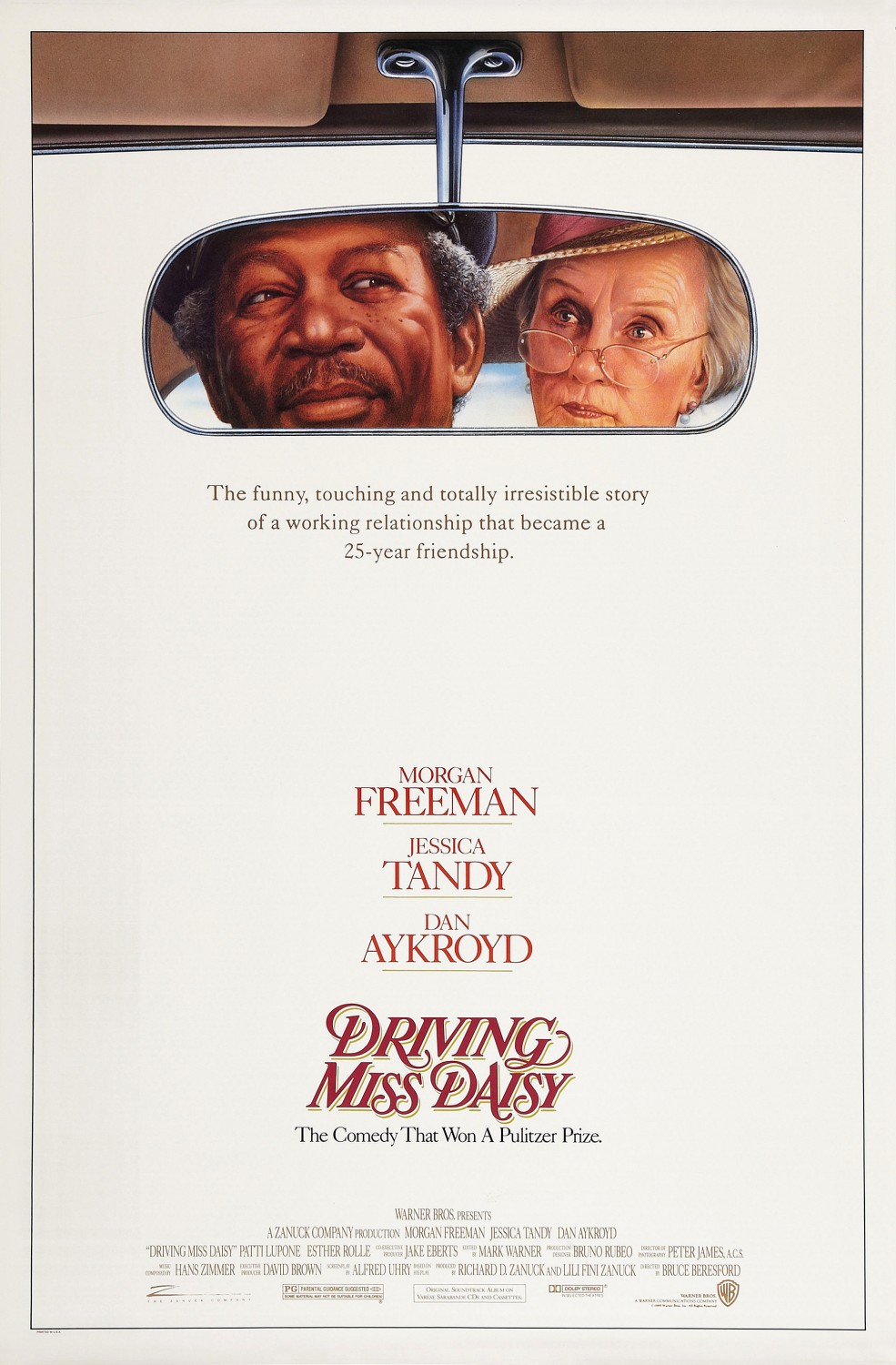

It appears the Academy loved almost everything about it, if we want to put stock in what they have to say—a risky venture, to be sure, but they agree with me here so let’s roll with it. It won the prestigious Best Picture award, the last one handed out on awards night. Morgan Freeman and Jessica Tandy were nominated for Best Actor and Actress, respectively (Tandy won). Alfred Uhry’s screenplay, based on his own Off-Broadway play, won the award for Best Screenplay. (It’s kind of a separate discussion, but the make-up team was justly awarded for their work too.) But there were no nominations forthcoming for Bruce Beresford, the first time the director of a Best Picture winner did not receive a nod since 1932, the third year that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences handed them out. Suffice to say that it is the chemistry between Freeman and Tandy, enlivened by Uhry’s pen and unfolding across the span of twenty-five years, that elevates Driving Miss Daisy into an emotionally rich experience.

The film begins in 1948 when the elderly Daisy Werthan (Tandy), a spunky upper-class Jewish widow, confuses the pedals in her car and crashes over her neighbor’s retaining wall. Her insurance rate skyrockets and her son Boolie (Dan Aykroyd), manager at a large textile factory, makes the executive decision to hire a chauffeur to keep her from getting behind the wheel. For this task he chooses Hoke (Freeman), an affable black man perhaps a decade his mother’s junior. Obstinate, Daisy initially rejects Hoke’s services. Not only does she walk or take public transportation so that she needn’t rely on his driving, she also berates him for tending to her garden, dusting her lightbulbs, helping her housekeeper Idella (Esther Rolle) prepare meals, etc. After these initial years of disdain, however, she begins to loosen up and allows Hoke to take on some regular responsibilities, including driving her to the store, to the synagogue, and to a birthday party across state lines.

Hoke: Did I ever tell you about the first time I ever been outside the state of Georgia?

Daisy: No, when was that?

Hoke: Oh, a few minutes ago.

But there remains a certain dynamic between them that comes naturally to Daisy, who was raised to treat people with dignity and respect but nevertheless harbors some deeply set notions about the proper state of things. Society would view Daisy and Hoke as an incompatible pair due to their dissimilar melanin levels, differing religious views, and distinct social classes. Indeed, when they are pulled over for a stretch of the legs while traveling for the birthday party, a pair of police officers crudely offer these exact sentiments.

While her initial distaste for Hoke stems directly from her son’s decision to hire him as a driver—a tension that is smoothed over in a few short years—even when she begins to treat him with some guarded warmth she remains oblivious to her ingrained prejudices. She is fond of telling her son that she does not have a prejudiced bone in her body, but her actions prove otherwise—in her lording interactions with Idella, in her generalized references to a stereotypical “them,” and so on. Late in the film, she invites Boolie to attend a dinner at which Martin Luther King Jr. will be speaking (achieved through the deft use of archival audio recordings). Boolie declines and suggests she invite Hoke to go with her. She half-asks Hoke just as he is dropping her off at the banquet, and, slightly insulted by the flippant manner in which she asked him, he remains in the car and listens to the speech on the radio. Blind to her missteps and warped view of the world, she even demands that Hoke stop talking when he tries to sympathize with her by comparing the bombing of her synagogue to a lynching he witnessed as a child.

Daisy never comes to see the wider picture but she comes to experience an inner change through her relationship with Hoke. The cultural barriers between them slowly melt away as the years pass and by the time Daisy must be put into the care of a nursing home, she admits to her chauffeur that he is the best friend she’s ever had.

With bold precision, Uhry’s screenplay and Mark Warner’s editing rapidly take us through a series of handpicked vignettes spanning a quarter of a century in an hour and forty minutes (remember when length wasn’t used as a stand-in for depth?). It is remarkable how dexterously we move into a scene, perhaps two or three years on from the last one, catch a small snippet of conversation that fleshes out the characters or provides emotionally resonant material, updates the audience on any important changes in the intervening period, and moves on. Some of my favorites are when Hoke admits that he can’t read when he’s asked to place flowers on a gravestone, prompting a quick spelling lesson from Daisy; and their bickering roadtrip to Mobile, Alabama which sees Daisy accusing Hoke of missing a turn while she holds the map and gives directions from the backseat.

I think the primary reason that Beresford didn’t get much attention, and also why it would absolutely fail if not for the strong performances, is that it barely justifies itself as a film. It was originally a vehicle for the actors’ talents and remains so when transitioned from the stage to the screen. Tandy is fantastic as the faux-independent elderly woman and is currently the oldest actress to ever take home the Best Actress award. She has several superb moments, including a remembrance of tasting the saltwater in the Gulf of Mexico as a young girl (she immediately chastises herself for being so silly as to speak her thoughts aloud to Hoke), and some savage insults delivered with real venom. Freeman, who reprised his role from the three year Off-Broadway run, carries the lion’s share of the trickier scenes, astutely observing the shifting sands of society with wry humor and subtle commentary in a multi-layered performance. And Aykroyd, known mostly for his comedic roles, is a wonderful surprise as the industrialist Boolie.

For better or worse, it never confronts its subject head-on, unlike, say, Green Book. It prefers to hint, allude, imply, with only a scant few instances that might make you really squirm. This gentle approach makes it easier to digest but leaves it without a real bite. It spans from just after WWII straight through the civil rights movement and takes place in the South, which puts us in some pretty tumultuous territory. But, as I’ve said, this is about Daisy and Hoke and their relationship over time, and the social changes that serve as an undercurrent are always happening just out of sight.

A heartwarming picture, Driving Miss Daisy sometimes gets picked on for triumphing over other films that are considered more deserving of the honors bestowed upon it. Though it is a conceptually simple story that mostly avoids addressing its touchy themes, it features two exquisite performances that capture an unorthodox relationship blossoming over the course of decades. It’s a feel good film, sure, but what’s wrong with that?