“We are supposed to be righteous. That’s a beautiful thing. And we’re losing it. If I lose that, that’s everything. That’s my soul.”

In the opening scene of Steven Spielberg’s Munich, a team of friendly and oblivious American athletes come to the aid of several Palestinian athletes. Stumbling upon the Arabs in the smoky half-light of dawn, the Americans, accustomed to crossing paths with small groups of men from different countries as they wander around the Olympic Village, amiably attempt conversation. Where are they from? Do they speak English? What events are they competing in? Deciding that the language barrier is insurmountable but uncomprehending of the apprehensive glances of the foreign men, the Americans blithely help them vault over a gate and depart with smiles. Before the Americans are out of earshot, however, the Palestinians have donned new outfits, produced assault rifles and grenades from their duffle bags, and infiltrated the lodgings of the Israeli Olympic team.

The rest of the disturbing episode plays out in a precisely arranged barrage of graphic imagery and archival newscasts, dominated by Jim McKay’s coverage in ABC’s Olympic HQ in Germany. “The peace of what has been called the ‘serene’ Olympics was shattered just before dawn this morning,” he says. Two uncooperative Israelis were killed immediately. Nine more were taken hostage. Authorities tacitly agreed to transport the terrorists and the hostages to Cairo while negotiations over the release of political prisoners continued, but at the airport, as McKay informs us, “all hell broke loose.” The ambush was botched and the hostages killed. “They’re all gone,” McKay mournfully declares.

This opening sequence is relentlessly gripping and ties Spielberg’s project to historical reality. However, it uses its tie to history only as a starting point. After the dramatic recreations and archival news footage, Munich proceeds to offer a fictionalized version of Mossad’s response to the massacre: a covert operation to assassinate the leaders of Black September, the terrorist group thought to have planned it. Well, calling it fictional is not entirely correct. It is based on George Jonas’ 1984 book Vengeance, purportedly a nonfiction work, but one whose veracity is impossible to prove because the clandestine actions of the operatives were not officially sanctioned by any authority. Let’s call it “inspired” by true events. In any case, the historical accuracy of the details provided in Munich is immaterial because, despite its ties to the factual event, Spielberg’s film isn’t aiming at an authentic recreation of the aftermath. Rather, it attempts to generalize the notion of a terrorist attack and society’s response to it; to abstractly explore the hazards of meting out justice under duress. That is to say, while Munich is obviously tied to a historical tragedy and its fallout, the director clearly thinks that the story has contemporary relevance.

If it has a message it is this: that vengeance is never the correct choice. Swiftly enacted justice might satiate a human desire for retribution, but knee-jerk reactions on a world stage will only propagate cycles of violence that reverberate across generations. Prolonged revenge, on the other hand, is a completely futile endeavor that gradually loses its meaning and insidiously destroys those committed to it.

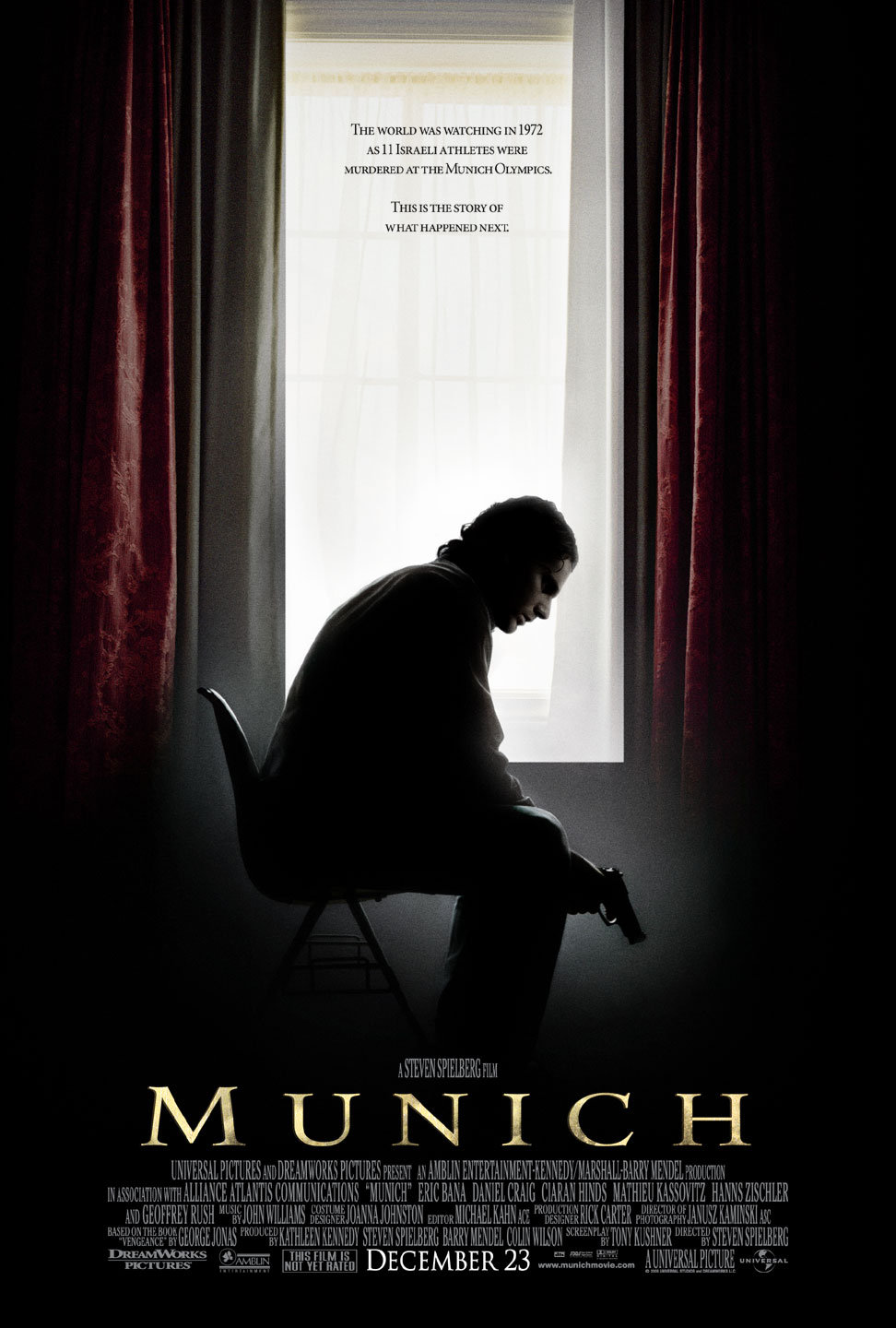

That being said, it’s hardly didactic. How could it be with its tangled themes and cast of morally gray characters? Eric Bana stars as Avner, a former bodyguard of the Israeli prime minister (Lynn Cohen) who leads a five-man hit squad in pursuit of the leaders of Black September. He’s joined by a driver (Daniel Craig), a bomb-maker (Mathieu Kassovitz), a “cleaner” (Ciarán Hinds), and a document forger (Hanns Zischler). Their assignments remain off the record for the purposes of plausible deniability and their lone contact within the Israeli government is a handler (Geoffrey Rush) who feeds them info on a need-to-know basis. Interestingly, the men selected to carry out the assassinations do not share the bloodlust of the authorities who chose them. Avner is detached but professional, looking forward to the end of his mission so that he can return to his wife and the newborn baby that he’s never met. Only Daniel Craig’s getaway driver openly voices his desire for revenge. The operatives track down their targets one-by-one with the help of a French anarchist (Mathieu Amalric) and his father (Michael Lonsdale) who will sell information to anyone who isn’t in the employ of a government.

But what begins as a series of intense precision assassinations gradually devolves into a morass of extravagant murders carried out with uncertain motivations. The tone shifts to match as a mission originally driven by righteous fury slows to a nihilistic trudge. The felled targets are quickly replaced by even more ruthless men, the terrorist cells respond to the team’s hits with more bombings and hijackings, and Avner and his team find themselves suffering from justified paranoia. The sense of moral uncertainty is occasionally discussed by the group when they question whether or not some of their assignments actually had a role in the Munich massacre. At first, Avner chooses to trust his government and even refuses to go after known enemies because they were not assigned as targets. On the first few hits, he dutifully confirms his targets’ identities before reluctantly pulling the trigger. However, after a certain point, he confesses that he could kill anyone without a pang of guilt. It doesn’t matter if they were on the list or not.

This moral atrophy is most clearly illustrated when one of Avner’s men, in a moment of weakness, falls into the arms of a charming temptress who also happens to be an assassin (Marie-Josée Croze). She was hired to kill his man because his man killed someone else. And now he must kill her in perpetuation of the endless cycle. He does so in brutal fashion, using a zip gun to pump a bullet into her chest, her breasts bared in a moment of panic as she tries to seduce him and his remaining men at gunpoint. Spielberg draws this out, allowing the woman to stumble around her houseboat, black blood spurting out with each harsh wheeze from her dying lungs. One of the men finally puts her out of her misery, but refuses to let Avner cover her blood-drenched nudity. It’s nasty on a level one wouldn’t typically associate with Spielberg, as her killing feels warranted and yet is both unsatisfying and atrocious.

There’s a scene where Avner and his team end up double-booked at a safehouse in Athens and improvise a cover as a group of leftist radicals to avoid a shootout with the Palestinians with whom they share the lodgings. Avner has a contentious conversation with one of the PLO members (Omar Metwally) about the validity of the Jewish state, nearly blowing his cover in the process, and manages to produce a meaningful dialogue. Avner asks the man if all of the bloodshed is worth the small patch of desert that they’re fighting for, which, as the man points out, is a question that could be asked to those on either side of the conflict. No, he says, the Palestinians will fight for generations if need be. It’s a mournful moment, echoed by the disproportionate retaliations that continue to escalate. That there’s no end in sight for the men in the trenches makes Munich one of Spielberg’s most cynical pictures.

While the film is a masterclass on many fronts, Spielberg does struggle slightly in trying to balance his middle-ground political stance with the fact that Jonas’ story reads like an exciting spy yarn. He attempts to corral an expansive story, with its large cast, divergent ideologies, thorny morals, and emotional burdens, and make a social statement (“All we are saying is give peace a chance.”), but to do so in the form of a stylistically varied and polished 1970s political thriller replete with riveting murder sequences. The film’s boldest moment, which intercuts Avner angrily making love to his wife with flashbacks to the massacre in an attempt to position Avner as a stand-in for his entire nation, feels miscalculated. Why is it those deaths (which he didn’t witness) that haunt him and not the murders that he himself committed? It should be noted that Spielberg’s signature visual style and manipulative use of music are mostly absent, even if his practical ingenuity is pervasive and subtly overpowering.

Though the film’s nearly three-hour runtime feels somewhat swollen, it’s difficult to say exactly what might have been excised to improve it. The assassinations provide excitement and tension, the exposition offers thematic rumination, and the frame story ties the film to the real world. Ultimately, I think its lengthiness feels unwarranted because it doesn’t build to a suitable climax—an intentional choice, of course, and one that underscores the message, but one that also leaves the viewer asking for closure that is not delivered.