“My world would’ve gone on turning just fine, but now, either way I look, I have to do something that I don’t wanna do.”

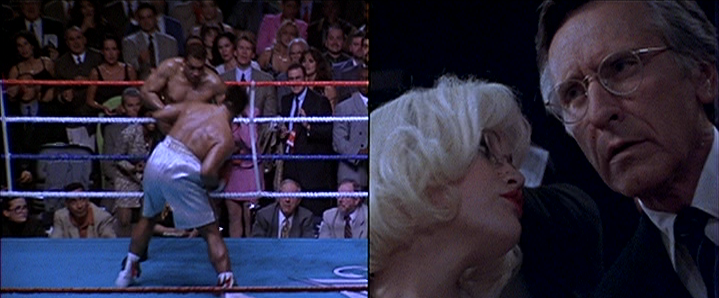

Snake Eyes begins with one of the flashiest shots in cinematic history. In masterful orchestration, corrupt cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) weaves his way through a stadium full of boxing fans. He places a bet, fields a handful of calls on his cell phone, including one from each of his wife and his girlfriend, enthusiastically tries to get the attention of the heavyweight champ (Stan Shaw), gives his number to a scantily clad ring girl, chases down, beats up, and robs a petty criminal, speaks to a reporter that he knows, takes his ringside seats next to his best friend Kevin Dunne (Gary Sinise)—who happens to be a Navy Commander and is there to protect the Secretary of Defense (Joel Fabiani) who is in the second row—and eagerly watches as his $10k bet is quickly lost. The shot only cuts when the defending champion hits the mat, which is the same moment that an assassin emerges and plugs the Secretary in the neck.1 It’s a signature sequence for Brian De Palma, but one that the rest of the film unfortunately does not live up to. The remainder of Snake Eyes formally plays out like a combination of Rashomon and Pulp Fiction as Santoro gradually uncovers a government conspiracy. It retells crucial sequences, subtly changing what the audience sees depending on whose eyes we are seeing them through. It repeats the same encounters from different camera angles, even utilizing playback from the tapes of the fight. But it gradually loses steam the longer it goes, petering out to a weird romantic sendoff that doesn’t seem at all consistent with the excitement generated by the opening scene. But even if it doesn’t match up against De Palma’s biggest successes, it’s certainly been underrated critically2 due to De Palma’s penchant for style over substance and the wildly varying quality of Nic Cage’s roles. Taken on its own terms though, there’s no denying that there are some masterful individual sequences here and that Nic Cage is at his manic best.

It was a gutsy move by De Palma and screenwriter David Koepp to put so much of the filmmaking effort into that initial scene. It provides many of the breadcrumbs necessary to follow the trail of the rest of the film and gives De Palma an opportunity to show off his flashiest tendencies. The combination of rapidfire dialogue and frenetic camera movement leaves the viewer mesmerized, without the necessary time required to process what they’re seeing. Who’s the mysterious woman sitting across the ring, not watching the fight? What is in the folder that the platinum blonde shows to the Secretary moments before his death? Wait, she’s wearing a wig? Why does a fight break out in the ringside seats? Why does Rick get a phone call just before the shot is fired? De Palma barely gives a chance for any of it to register before the gunshot rips through the air.

It’s basically impossible to comprehend the amount of careful planning and rehearsing that must have gone into orchestrating the movements and timing. The camera is constantly on the move and someone is talking almost the entire time, not to mention there are literally thousands of extras in the arena and a choreographed boxing match going on. Cage obviously has the toughest assignment. His mannerisms are a little bit excessive, but simply memorizing all of the dialogue would probably be an impossible task for many. Similar to the opening shot in Boogie Nights, we’re introduced to every important character in this single shot. De Palma’s camerawork showcases the shot’s unbrokenness with deliberate pans and swoops, but even so, when the cut finally comes, you’re bound to sit back in admiration of the complexity and ingenuity of such a magnificent display of filmmaking bravura.

Even the harshest critics of Snake Eyes will allow that this first scene is brilliant. The ensuing three quarters of an hour are also solid, if not on the same level of brilliance. In this section of the film, Santoro begins to uncover a conspiracy in a reconstructive fashion similar to De Palma’s Blow Out and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, both of which took inspiration from Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up. Instead of the photographs of Blowup or the sound clues of the other two films, Snake Eyes utilizes visual clues in the form of video surveillance, tracking sensors, newscasts, and fight reels. The most crucial reel was recorded by one of those mini-blimps that float around at sporting events. In a series of Rashomon-esque retellings of the pivotal event, the self-serving Santoro is forced to uncover his own moral limits on the fly as he hones in on the bleak truth: his best friend led a conspiracy to have a government official assassinated.

These alternate angle sequences reveal superb attention to formal detail. We see Santoro performing the same actions from different vantages and it almost feels like these moments were indeed captured from multiple angles (I’m not sure if that’s true or not, but if so, that’s another feather for De Palma’s cap). The narrative remains fairly strong in this section as well. Using the “corrupt cop” angle, Santoro’s questionable decision-making takes us on a fun ride. Initially, Santoro focuses on covering his friend’s back by whatever means necessary. It does not matter to him that Dunne left his post and followed an obvious decoy, becoming distracted by her flirtations.

Dunne: I was three feet away from a known terrorist, and I had my eyes buried in some broad’s tits.

Santoro: Well, Kevin, this may not make you feel better, but don’t you see? That’s what she was there for. That was the plan. To give you a boner. And you got one. Congratulations, you’re human.

Santoro is there for his friend. He knows how to play the game. He devises a story for Dunne to tell and uses his own rough demeanor to ward off any suspicious eyes until federal agents arrive. He locks down 14,000 people in the adjoining casino, barks orders at local law enforcement, and then sets off on his own little investigation: why did the champ throw the fight? Just after the shots were fired, as Santoro lay on the ground and pulled his own weapon, the “knocked out” boxer looked around, awake and alert, locked eyes with Santoro, and then once again feigned unconsciousness. But Santoro doesn’t immediately connect the two events. Cage does his calm-crazy routine when Santoro confronts the former champ and blackmails him into paying him back his betting losses and giving him an autograph for his son.

Then, in pursuit of the young lady who exchanged words with the Secretary just before the assassination, Santoro uncovers the real conspiracy, which involves military defense and millions of dollars. Disparate threads come together in his mind, and when he finally sees the blimp camera footage, which does not reveal Kevin Dunne distracted by a pretty lady, but Kevin Dunne waiting patiently for the shots to be fired, his world goes topsy-turvy. I think the primary reason that people dislike Snake Eyes is that at this moment, the film has climaxed. Santoro has essentially solved the crime, at least as thoroughly as you could expect in a film that takes place basically in real time. But instead of wrapping things up neatly (which wouldn’t work for a feature film because we’re only like an hour in at this point), De Palma strings things out and turns the film into a character study of Rick Santoro. This only partially works because Nic Cage does some wonderfully dynamic work, but there isn’t enough story left to buff out another thirty minutes. Dunne’s explanation for orchestrating the plot feels incomplete and insincere (although Sinise delivers it with plenty of passion), and the exploration of Santoro’s moral limits are lost amidst an unbelievable finale. De Palma has stated that the film isn’t about the conspiracy but about the broken relationship between Dunne and Santoro, which is fine, but that’s not as exciting as the conspiracy; and ending the conspiracy so early makes the rest of the film an uphill battle.

There are a few symbolic connections from De Palma and Koepp that are easily lost amidst the rapid chaos. The yin and yang of Santoro and Dunne, one a decorated Naval commander with a heartless mission, the other a rowdy playboy with a deep-seated sense of moral duty. A connection can be made between the fixed boxing match and the conspiracy, in which the champ’s adversary and Santoro perform against expectations. There are two women dressed in disguise, one taking part in the conspiracy, one the target of it. Do these mean anything? I don’t think that it’s really worth digging into.

I would certainly prefer that the film had a more cohesive narrative, but I’ll take what I can get. I really enjoy De Palma’s fancy camerawork, his use of split-screen and first-person point of view, and the long planned shots. It’s a masterclass and technique and style. The flamboyant role of Rick Santoro wouldn’t work with anyone but Nicolas Cage, and he gives us one of his most dialed in “crazy” performances. I think it would be disingenuous to gun this down and tag it as a failure, even if it has some critical issues that wear away at its lustrous shine.

1. There are at least two camera movements in the long stretch where I think they might have cut. But regardless, there are very long stretches of unbroken, carefully planned movement and dialogue that are no less noteworthy if there was a disguised cut at these points.

2. Roger Ebert gave it 1/4 stars… it’s not that bad at all.