“Chaos is order yet undeciphered.”

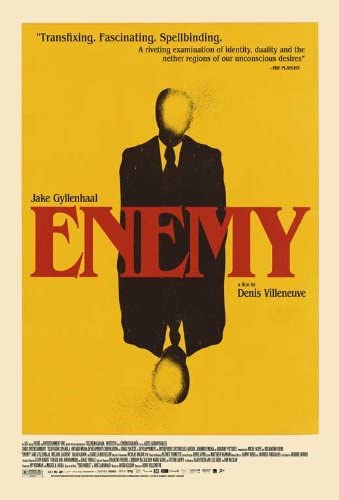

Denis Villeneuve burst onto the American scene in 2013 with two features starring Jake Gyllenhaal—the blockbuster kidnapping mystery Prisoners and the arthouse head scratcher Enemy. While the former garnered a lot of mainstream attention (it co-starred Hugh Jackman and its box office returns were more than thirty times those of Enemy), the latter’s symbolism, thematic intensity, and elusive plot give the viewer much more to chew on once the credits roll.

Based on the novel The Double by Portuguese author Jose Saramago, the plot is simple on the surface; its appeal lies in the tangled web of symbolism permeating the film as well as the unclear plot. Where Prisoners portrays a real, physical conflict between people, Enemy is concerned with mental perplexity and paranoia. Jake Gyllenhaal plays two roles: Adam Bell, a disgruntled and miserable history professor, and Anthony Claire, an aspiring actor. Late one night, after his girlfriend Mary (Melanie Laurent) has gone to sleep, Adam watches a movie on his laptop that a talkative work colleague had suggested to help lift his spirits. As he mindlessly watches the obscure film, he doesn’t even register seeing his doppelgänger; it isn’t until he dreams of the scene that his mind makes the connection, and he becomes obsessed with tracking down Anthony Claire.

When Adam tries calling Anthony at his house, he is initially met with hostile responses from Anthony and his wife, Helen (Sarah Gadon), who is visibly pregnant. Prior to the men meeting face to face, the similarities between their lives become apparent. Both struggle to find fulfillment in their careers, achieving only middling success in their chosen fields; and both suppress their feelings of discontent regarding their circumstances. Their blonde partners both struggle to love them back due to their various shortcomings—notably Adam’s reticence and Anthony’s suspected infidelity. When they finally meet face to face, only more questions are raised. The men are incredibly similar, their differences exclusively emotional and dispositional; they even share the same scars. Gyllenhaal does exceptional work infusing each character with the subtle differences required to differentiate them, utilizing a versatile skill set that would be on display again in the dual-role Nocturnal Animals.

The film’s pervasive symbolism is prominent from the opening scene, in which an anonymous Gyllenhaal observes an erotic show at a secretive club, which culminates in a nude woman carefully pressing her stiletto heel down on top of a tarantula. The camera lingers on various objects that bring to mind spiders and webs—a lattice of wiring, a cracked car window, literal gigantic arachnids standing taller than skyscrapers—in an unnerving case of frequency illusion. The protagonist’s cognitive biases linger on anything that could be used to affirm his own preconceptions. After their initial encounter, Adam regrets having made contact, but Anthony is eager to take his anger out on his twin as the constant phone calls had led Helen to suspect that he was cheating on her.

Anthony attempts to assert his dominance by forcing Adam to let him take Mary on a short vacation after which he promises to disappear from their lives forever. Adam agrees, but when they leave, he returns to Anthony’s apartment in hesitant retaliation. He is welcomed into bed by Helen, and as the two curl up next to one another, she asks him how school was that day, revealing her knowledge of the imposter.

While Anthony and Mary make love on their vacation, Mary freaks out when she notices the tan line on Anthony’s ring finger. Though he tries to soothe her, they decide to return home, but their arguing causes Anthony to drive recklessly. As he loses control of the car it swerves, flips, and then skids to a halt as a crushed mass of metal and glass. In the startling final scene, Adam turns a corner to speak with Helen, and is confronted by an enormous tarantula that fills the entire room (a face-to-face encounter with the physical manifestation of distress that Villeneuve would repeat several years later with a heptapod in Arrival).

The film’s muted yellows, deep shadows, and harsh lighting give it a visually depressing and sickly look, which fits well with the theme of unfaithfulness and self-loathing. This visual aesthetic is coupled with a slow pace which builds suspense and creates the film’s cinematic atmosphere. The most coherent interpretation of the film is to consider Adam and Anthony as a single person trying to break free from the tainted mentality of discontentment, lust, and infidelity. The tarantula and its webs represent his affair with Mary which still hangs over his marriage with Helen; or perhaps, it represents the mental sickness which led to the affair and from which he desperately desires to be set free. Anthony then, is Adam’s unfaithful alter ego who had infiltrated his home life, but who metaphorically dies along with the adulteress at the end of the film. When Adam is presented with a key that would grant him access to the underground club, his wife turns into the tarantula, representing the impending descent into the same hell from which he had just escaped. This symbolic interpretation requires the viewer to understand many of the scenes—interactions between Anthony and Adam, the car crash—as completely symbolic; visual representations of Adam’s mental processes.

Gyllenhaal’s dual role stands out as he infuses each of his characters with enough depth that they seem like different people. His performance stands up well against other notable dual roles, such as Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman in The Prestige, Sam Rockwell in Moon, and Jeremy Irons in Dead Ringers. Villeneuve’s creative choices owe much to the stylistic and thematic tendencies of Ingmar Bergman, Krzysztof Kieślowski, and Michelangelo Antonioni—all foreign directors like Villeneuve whose personal, contemplative films eventually found footing in the international market.

The film is needlessly dull at times, likely done with intention to emphasize the mental state of its characters. The stark color contrasts, while stylish, overstay their welcome; some scenes are simply too dark, losing interesting visual details in the shadows. But those are minor gripes, in what is otherwise an intense and interesting film. It gains major points for its unapologetic approach and unwillingness to explain its slippery narrative—indeed, films like Enemy are often best left without a definite explanation, as the experience of watching the mystery bloom is much more gratifying than elucidating its underlying logic.