“In the world of advertising, there’s no such thing as a lie. There’s only expedient exaggeration.”

When Ernest Lehman set out to pen North by Northwest, he did so with an eye toward crafting “the Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures.” Indeed, the resulting film can be seen as the apotheosis of its director’s wrong-man-pursued template, so archetypal that it occasionally borders on self-parody, even if it is so exquisite in execution that in each case its pure entertainment factor easily outweighs the fact of its self-awareness.

Cary Grant, in his fourth and final collaboration with Hitchcock, plays Roger O. Thornhill, a twice-married, twice-divorced advertising executive who finds himself caught up in a web of international intrigue when he is mistaken for a government spy. He’s kidnapped and interrogated by an archvillain named Vandamm (James Mason), but when he denies his alias—because, of course, he is not the spy—he is nearly killed, then arrested for drunk driving and grand theft auto, then framed for the murder of a high-ranking diplomat at the U.N. General Assembly building.

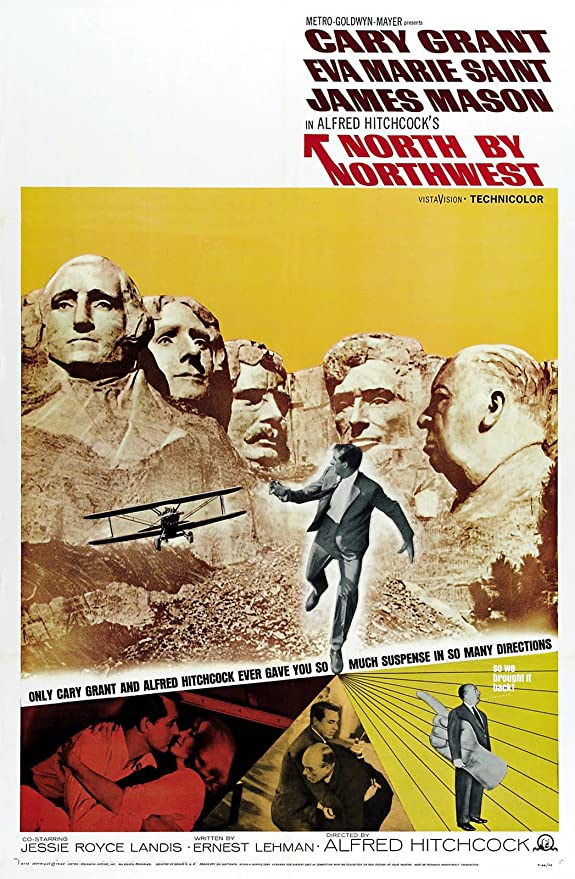

And just like that, he’s a fugitive on the run, discreetly traveling across America in the frantic pursuit of justice. Aided by a femme fatale (Eva Marie Saint) who first hides him from the authorities and then seduces him over dinner on a train, Thornhill’s adventures take him from the hustle and bustle of New York City to an art auction in Chicago, from the dangerous cropfields of rural Indiana to the carved visages of Mount Rushmore, all the while pursued by the police, the CIA, and Vandamm’s henchmen.

It’s similar in scenario to Hitchcock’s Rear Window—with a civilian gathering criminal evidence to support the truth of his own claim—but opposite in its use of locations: where the earlier film is essentially confined to the courtyard and adjacent apartments, North by Northwest spans across the country (at least in theory; much of it was filmed on sets). While I prefer the intricacies of the intimate setting, the large-scale set pieces here are quite invigorating.

As Thornhill goes to increasingly drastic lengths to clear his name—bluffing his way into the hotel room of the spy, escaping a fighter plane equipped with machine guns, stealing a truck, secreting himself aboard a train, infiltrating Vandamm’s hideout, working with a government handler (Leo G. Carroll), tangling with menacing goons (Martin Landau)—he more or less becomes the agent that Vandamm initially mistook him for. Though he begins the film as nothing more than a smooth-talking businessman, he ends the film as a proto–James Bond figure in cinema. (Ian Fleming had written a half dozen Bond novels at the time, but Dr. No was still a few years away. After North by Northwest, Grant became the first choice to play the character.)

The screenplay spirals delightfully, upping the ante on Thornhill’s predicament again and again, throwing a magnificently distilled MacGuffin into the mix, building tension while sprinkling in enough hints to keep the viewer fully engaged rather than just waiting for the next reveal. The incongruous plot requires a massive suspension of disbelief, which we’re willing to grant because of the bravado sequences and magnetic performances. It also helps that Grant plays Roger Thornhill as perpetually amused by the outlandish developments.

Unlike many of Hitchcock’s other well-regarded thrillers, there’s a sense of playfulness to North by Northwest due in large part to Grant’s game participation. The darkness that tinges Vertigo and Rear Window is replaced with comical asides, facetious banter, a goofy mother-son dynamic (Jessie Royce Landis, who plays Thornbill’s mocking mother, was only a few years older than Grant), a fine bit of drunken acting, and a wonderful capstone of visual innuendo to close things out. Deeper themes emerge if you want to look for them, but they’re all subsumed into the film’s commitment to popular entertainment of the highest order.