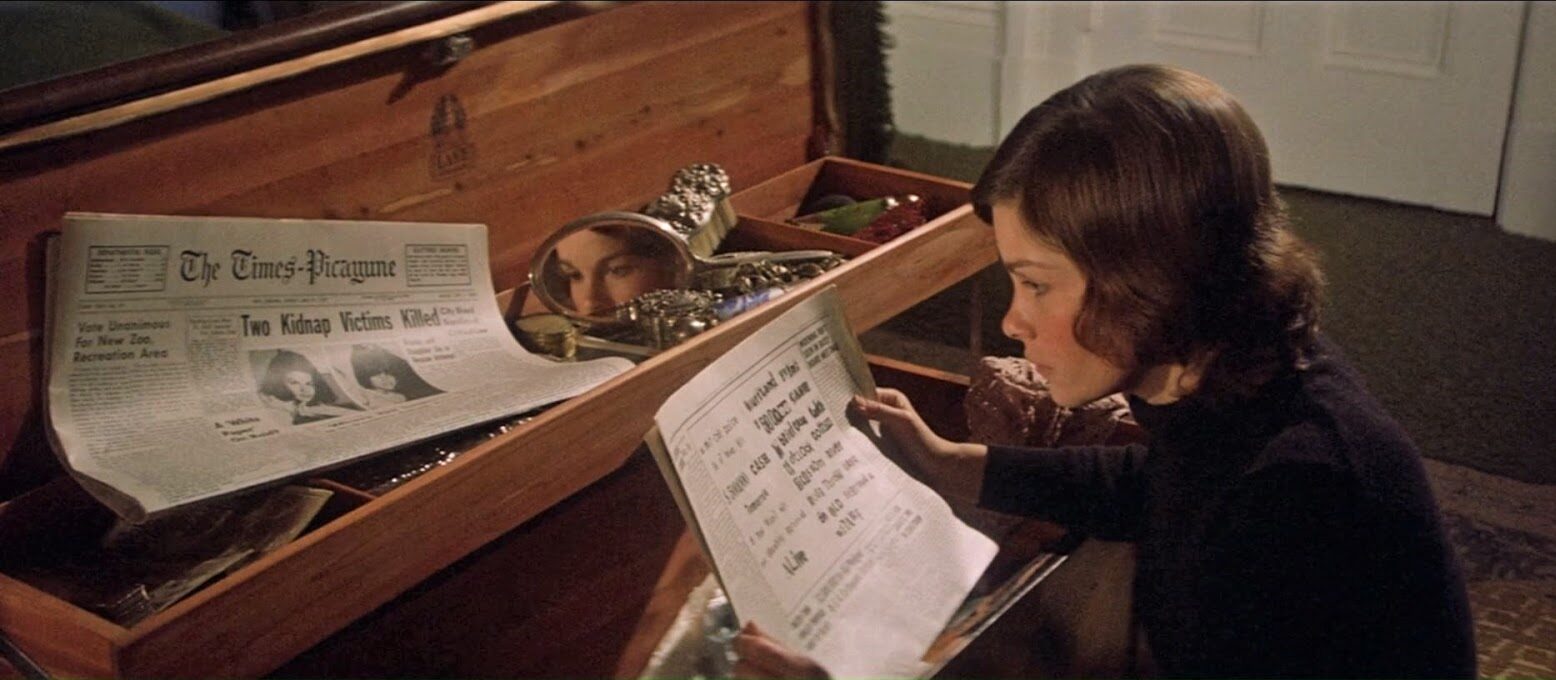

“The plot thickens. Let us sit and tell sad tales about deserted daughters and lonely husbands.”

When Michael Courtland (Cliff Robertson) happens upon Sandra Portinari (Geneviève Bujold), the young doppelgänger of his deceased wife, in the same Florence cathedral where he met his beloved all those years ago, they discuss the restoration work being done on a Madonna. Some damage to the portrait has revealed an older one beneath it. What’s to be done in such a situation? To remove the top layer would destroy a work of art, to restore it with modern elements would conceal the original work underneath.

Michael suggests that it be left in its patchy, chaotic state, clueing us in not only to his peculiar fascination with this human reminder of his past trauma, but also to director Brian De Palma’s blueprint for making Obsession—that is, to let an older work (Alfred Hitchock’s Vertigo, but also Rebecca and a few others) show through the surface of an incomplete one inspired by it; and to let that uneven amalgam stand as its own piece, a dangerous collage contrasting Golden Age Hollywood with the New Wave.

The results are a mixed bag, effectively utilizing much of Hitchcock’s cinematic vocabulary and hurtling forward on the back of Bernard Herrmann’s score and Vilmos Zsigmon’s soft focus photography, digging into De Palma’s preoccupations with doubles, deception, and emotional fixations, yet often feeling like a calculated exercise that lacks the natural chutzpah to glide past the narrative hiccups that result from the experiment (which typically go unnoticed when they show up in a good Hitchcock).

That is to say, my impression is that De Palma and screenwriter Paul Schrader were more intellectually than emotionally stimulated by Vertigo. And so while Obsession meticulously recreates the manner of the earlier film (just as many great films from the cinema-obsessed Movie Brats reference their influences), it fails to replicate its feverish pulse—an outcome reinforced by the sheer volume of showboat citations of Hitchcock films which create an emotional distance between the viewer and the primary text of the film. Without Bujold’s poignant performance, it might have been totally devoid of mystery and vitality. Still, as Michael and Sandra commit a folie à deux with assistance from Michael’s conniving business partner (John Lithgow), the film pulls off a few affecting tricks, such as an extended sequence where Bujold is inserted into memories from her childhood and a nigh-endless revolving shot during an emotional crescendo that comes after a near catastrophe.