“If a person has no love for himself, no respect for himself, no love of his friends, family, work, something, how can he ask for love in return?”

As Noel Murray points out in his piece for The Dissolve, the most famous sequence in Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces does not encapsulate the film very well at all—perhaps none of its individual segments do—but it does enlighten us to the lost soul at the center of its character study. Pit-stopped at a roadside diner somewhere between Southern California and Puget Sound, Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson) viciously snaps at a waitress who refuses to let him deviate from the items listed on the menu. He reasons his way around the silly rules by requesting a chicken salad sandwich sans the chicken salad so that he can get what he really wants: a side order of toast. “You want me to hold the chicken, huh?” the waitress asks. “I want you to hold it between your knees.” Stripped of its context, the moment is caustically funny, but the rest of the film is neither as comedic nor as openly hostile as this exchange suggests.

And anyway, the most crucial portion of this encounter happens afterward, back on the road, where one of the hitchhikers (Helena Kallianiotes) riding along with Bobby and his girlfriend Rayette (Karen Black) admires his ability to cut through the diner’s rules and get his toast. “Yeah, well, I didn’t get it, did I?” he says. “No, but it was very clever.”

That throwaway exchange, much more so than the famous sequence that precedes it, provides a frame around the character of Robert Eroica Dupea, a gifted but self-destructive man who can’t seem to settle on any goal, let alone apply himself with enough commitment to achieve one. A restless malcontent, Bobby was born to a wealthy family of musicians who named him after a Beethoven symphony. He resents it all, and has long since buried his past life as a classically-trained piano prodigy in favor of the drifter lifestyle, whimsically bouncing from one situation to the next, driven by unpredictable impulses, stranded between myriad indistinct personal identities. But even as he finds himself perpetually and proverbially alone in a crowded room, staring off into space or sardonically ripping into those around him, the insecure child within occasionally emerges.

Like its protagonist, Five Easy Pieces is unpredictable. Its first half, which details Bobby’s freewheelin’ lifestyle and fleshes out several minor characters, gives no indication of its second. In a sense, the first act is one big digression. But in a film more concerned with character and behavior than plot, all of it factors in. At the beginning of the film, Bobby has marginally settled down in Southern California with the ditzy Rayette who works as a waitress and dreams of becoming a country singer. An oft-cited moment comes early when Bobby enters their house to hear the sounds of Tammy Wynette’s ‘Stand By Your Man’ and scowls at the gramophone. Despite her foolhardy loyalty to him, Bobby has little respect for Rayette. He speaks down to her, refuses to reciprocate her sweet nothings, and blatantly cheats on her without remorse. When he’s not boozing or whoring, he’s working in the oil fields with his blue collar pal Elton (Billy “Green” Bush) or throwing strikes at the local bowling alley. Sometimes, though, his sordid inclinations encroach on his innocuous hobbies.

The film pivots when Bobby learns that he’s impregnated Rayette. The unwelcome news provides sufficient impetus for him to quit his job and drive to LA where he visits his sister, Partita (Lois Smith), who stuck with her musical training and now plays professionally. The cheerful visit quickly turns bleak when Tita informs Bobby that their father, from whom Bobby has long been estranged, is very ill. He tries to curtail the conversation and skidaddle but Partita is persistent and eventually he agrees to drive up to the family commune and make peace with his ailing father (William Challee) while he still has the chance.

After a mini road movie in its middle portion (complete with an anticonsumerist diatribe), the film settles into a third act that is tonally distinct from what preceded it. On the island where he grew up, which every fiber of his being wanted to escape and dreads to return to, Bobby finds a situation that’s not unlike every other one he’s found himself in as an itinerant adult. His brother Carl (Ralph Waite) is friendly but distant; his father is a vegetable who doesn’t even recognize him; his sister is supportive and doting, even as she pines after their father’s male nurse (John Ryan). He would gladly put it all out of sight and mind except for his brother’s fiancée, Catherine (Susan Anspach), who proves irresistible to Bobby despite the fundamental disagreements in their worldviews.

Five Easy Pieces is defined less by the broad strokes than by the narrow ones—the memorable lines of dialogue, the fully-realized characters, the images that linger—which, taken altogether, amount to a work that’s more than the sum of its parts. Rafelson, who conceived of the story and hired his pal Carole Eastman (alias Adrien Joyce) to write it, circles his subject in a nearly distracted manner, but pleasantly so. Little flourishes abound, most of them coming from the screenplay. There’s a beautiful diversity to Eastman’s dialogue, which bridges varieties of American vernacular, from the pompousness afforded to the wealthy Dupea family to the clever vulgarities of Bobby (“Where the hell do you get the ass to tell anybody anything about class, you pompous celibate?”) to the redneck slang employed by Ray (“That stupid thing just goes all cocky-wobbly, honey.”). Bobby shifts his language depending on the audience and whether or not he intends to wound the target of his speech, just as his name changes from Bobby to Robert when he returns home.

The rich dialogue brings Five Easy Pieces to life and gives it staying power. Take the early exchange after Bobby looks disapprovingly at the record player, for instance. Rayette wants to play the song again, but he refuses. “You play that thing one more time, I’m gonna melt it down into hairspray,” he says. She then suggests that he flip it over and play the B-side. “No, Rayette, it’s not a question of sides. It’s a question of musical integrity.” Nicholson delivers this line with his trademark smile, his partner unsure what the comment means but comprehending that he’s putting her down. In that small interaction, we are given great insight into Bobby’s misanthropic character. He looks down on those who can’t hang with him on an intellectual level. And yet, when he finally meets a match in Catherine, he crumbles.

Consider the scene where he plays a simple piano piece for her which evokes an emotional reaction. He laughs at her tears and mocks her emotions. “I faked a little Chopin and you faked a big response.” But she wasn’t faking, and this disconnect between them reveals the utter hopelessness of Bobby’s disillusion. He’s insincere about everything and thinks everyone must be similarly hollow, only faking geniune human connection, which for Bobby, does not exist.

Like Kristofferson’s Pilgrim, Bobby Dupea is a walking contradiction. This is no more clear than when he and Elton get stuck in traffic and he decides to climb up onto a moving truck stopped just ahead of them and begin playing a piano strapped to it. He becomes so absorbed in his impromptu performance that he continues playing even as the truck drives off. Toward the end of the film we are given a glimpse into the past, a hint at what might be at the root of Bobby’s discontentment. Taking his invalid father for a walk in the field, just the two of them, Bobby tentatively eases into a one-sided conversation. We get a sense that Bobby was not quite talented enough for his father’s liking, even if he’d elected to pursue a musical career. It’s a sad monologue in which he admits that if his father could talk, they probably wouldn’t be having the conversation at all, and it ends with an honest apology but no real closure. There’s no evident solution to Bobby’s identity crisis, but we at least see that he is human after all, which belies, however marginally, Catherine’s excoriating assessment of him.

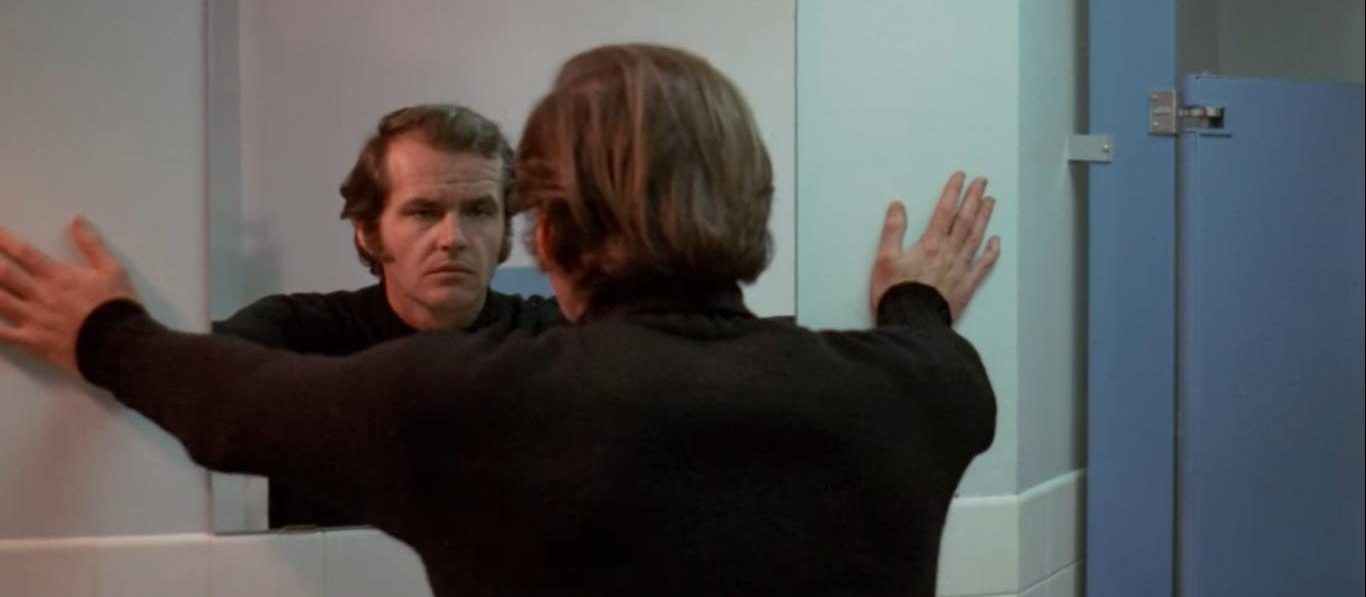

It’s those quieter moments that create a lasting impression: László Kovács’ stylized composition that frames Bobby in silhouette against the oil field after he quits, his silent tantrum in the car, his contemplative moment alone on the beach when Catherine spurns him, the long stare into the truck stop bathroom mirror before he abandons Rayette for a new phase of life, the harrowing final shot that holds through the end credits. Those and the quirky deep cuts that authenticate even the smallest roles, like the vulgar little ditty that Elton bangs out on his mandolin in the car or Partita’s penchant for ruining her piano recordings by humming along out of tune or Carl’s insistence on playing ping pong despite his neck injury. These little throwaway bits of flavor are uplifted by a scissor-happy pair of editors (Christopher Holmes, Gerald Shepard) who mercilessly remove extraneous material by heavily relying on cinematic shorthand and the audience’s careful attention. Where lesser films would include a few shots to indicate a change of setting or the passage of time, there’s often just a cut. What’s interesting, of course, is that the very things that make Five Easy Pieces so compelling are the same ones that would hit the cutting room floor early in the production of a plot-driven Hollywood film. But Five Easy Pieces is not a Hollywood film. Rather, it is one of the few releases from BBS Productions, an independent production company that for an all-too-brief moment in time crafted formula-defying, arthouse-informed auteur pieces.