“I know it’s a rotten game, but it’s the only one The Man left us to play. That’s the stone cold truth.”

It’s an understandable shame that Super Fly is seldom mentioned in the same breath as other early 1970s crime classics like The Godfather, Mean Streets, Chinatown, Klute, Badlands, &c. The New Hollywood boom was an amazing time when outsiders were able to rise to prominence, anti-heroes became mainstream, formal creativity was encouraged, and the lurid elements previously restricted by the Hays code found a home in the auteur’s wheelhouse. Operating in parallel to this movement but outside of the traditional system was the blaxploitation industry, a meta genre of exploitation cinema that incorporated popular trends into low budget films with predominantly black casts. The movement was unofficially kicked off in 1971 by progenitors Shaft and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, though there were prototypes well before then. Both films were big crossover hits, raking in $10M+ each, which gave greedy studios a reason to pump some money into such films and led to an explosion of underground classics, Super Fly among the earliest of the seminal entries in the canon.

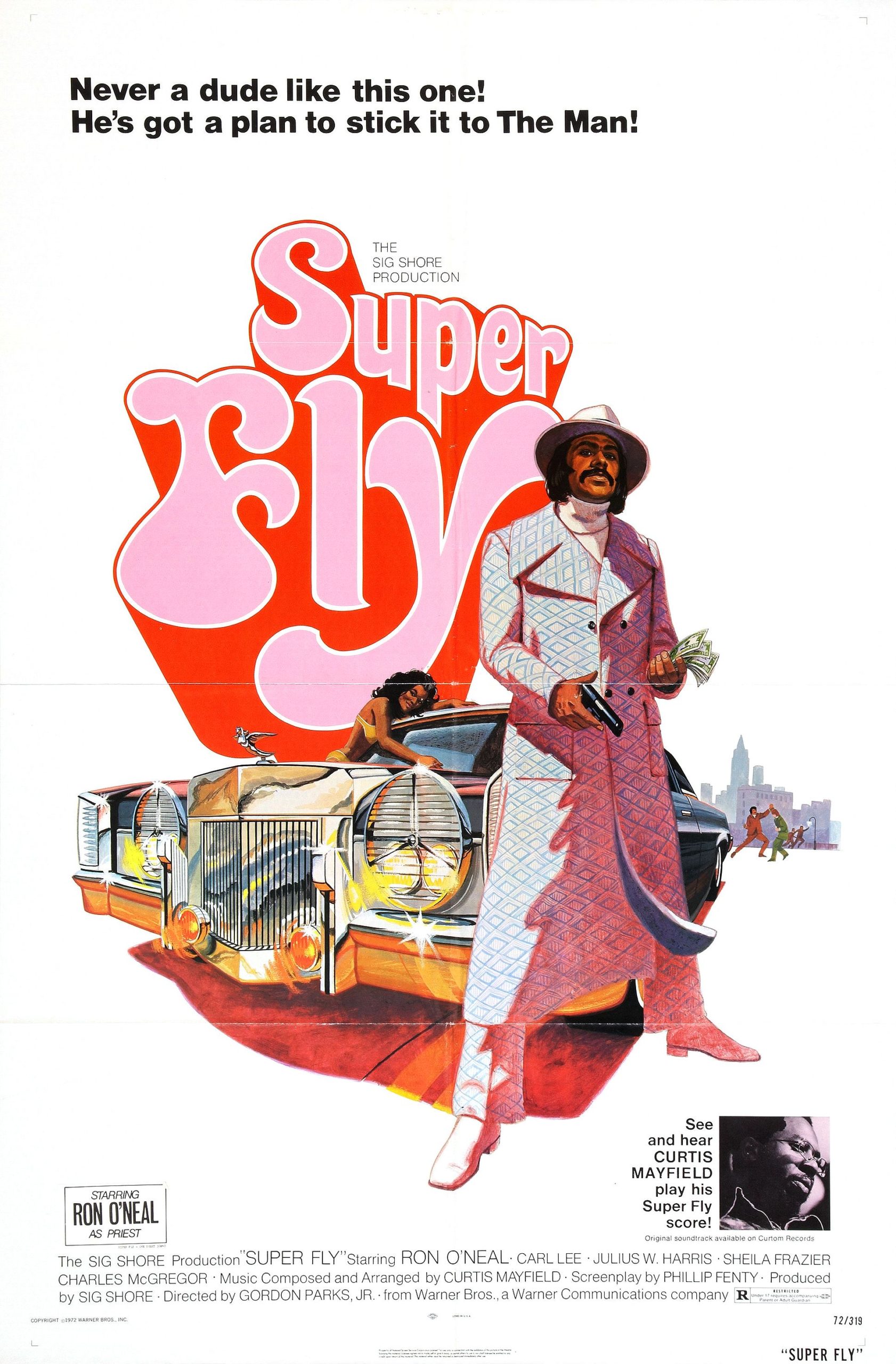

Super Fly is a gritty tale of a mid-level drug dealer looking for one last big score before getting out of the trade. It features lo-fi camerawork, cartoonish slang, improv, flamboyant 1970s fashion, and a hit soundtrack. All of these elements work together to conjure a cinéma vérité-style view of the seedy Harlem underworld. At the center of the story is Youngblood Priest (Ron O’Neal), a cocaine-fueled tough guy who sports mutton chops, trench coats, and fedoras. He’s living a twisted ghetto version of the American dream—he’s the boss of a small dope empire, loose women slumber in his bed, and he has access to all the cocaine he can snort. But it’s not the life he chose for himself. Rather, it was forced upon him by the dearth of suitable opportunities for an enterprising black man. Despite all of these material comforts, he wants out. He knows that a life of crime will inevitably lead to prison or an early grave and wants better for himself. His plan is simple: put up the $300k that he and his partner Eddie (Carl Lee) have saved, buy 30 kilograms of the highest quality cocaine, sell it all in four months, then split the million in profits between them.

But all of the people around Priest, those who try to inform his thoughts, see things differently. Eddie balks at Priest’s proposal. “You gonna give all this up? Eight track stereo, color TV in every room, and can snort half a piece of dope every day. That’s the American dream!” His girl, Georgia (Sheila Frazier), wants him to get out, but doesn’t think his risky gamble is worth it, preferring that he quit immediately to start a new life with her. Scatter (Julius W. Harris), his supplier, doesn’t feel comfortable getting him such a large quantity of dope all at once, and his white side chick doesn’t understand his desire to leave his life of status and material surplus behind. But Priest is a driven man and he forges ahead with his plans, leaving a trail of bodies behind him, friends and enemies alike.

Super Fly is not so much about the world of dope dealing as the more abstract idea of rising above one’s circumstances. In order to explore this concept, Phillip Fenty’s script depicts Priest as a traditional anti-hero—a criminal with a strong moral compass, constantly conflicted with his choices but acting according to a higher principle. His mixed up feelings are expressed most clearly when he makes himself vulnerable to his women. To Cynthia (Polly Niles), a coke-head who hangs around him for his money and drugs, he confesses that he used to truly think he wanted all these things he hates—the money, the power, the sex, the drugs, the cars—but that they are hollow pleasures for him now. He tells Georgia that although he plans to leave his life of crime, he cannot do so without a last big score; he would rather die than go back to “working some jive job for chump change.” Pressed to give an answer for what he will do once he’s out, he describes having the simple freedom to choose as his motivation. Part of the film’s understated brilliance is that it offers a perspective that precludes the opportunity to fingerpoint. Priest is unequivocally a criminal, but there isn’t really any room for us to judge him. He’s there because of the hand he’s been dealt, struggling like mad to make something better for himself. It’s not his fault that his avenue for doing so involves choices with unfortunate consequences.

I don’t know. It’s no so much what we do. It’s having a choice, being able to decide what it is I want, not just to be forced into a thing because that’s the way it is. Gonna buy me some time, baby, some time that isn’t all fucked up with things we gotta do. Just to be free.

A further wrinkle in Priest’s character is inherent in O’Neal himself. As a light-skinned black man with straight, shoulder length hair, the actor struggled to get roles early in his career. He cut his teeth in amateur theater and won awards for his role in Charles Gordone’s No Place to Be Somebody, the first off-Broadway play to win a Pulitzer Prize. But he did most of his early acting for free and was looking to make a career of it. He did a few bit parts in film but was told he wasn’t dark enough for parts written for black leads, including the lead role in Shaft. He longed to do Shakespeare on the stage but wasn’t light enough for the directors there. Caught between a rock and a hard place, he worked on a treatment for Super Fly with his friend Phillip Fenty, with the intention of starring in it himself. This personal element is played out early in the film, when Priest interrupts Eddie’s dice game. One of the players, annoyed that he won’t have a chance to win back the money Eddie’s taken from him, gets in Priest’s face and remarks on his light skin. Priest punches him in the face.

After some initial obstacles, Priest gets his escape plan off the ground. A police lieutenant reveals himself as a source, a virtually unlimited supply for Priest and Eddie to sell to their hearts’ content. Although Eddie is ecstatic about the future prospects, Priest sticks to his plan. At this point in the film, director Gordon Parks Jr. made an elegant choice. Whether forced by constraints of budget or time or a deliberate decision, the distribution of the thirty kilo shipment is shown via photo montage. Dozens of consumers are shown exchanging their money for dope, imbibing, and enjoying. Some of them are poor, some rich; some white, some black; some are shown only briefly as pieces of a collage, some are given sharper focus. The photos are creative and capture a variety of consumptive methods. The film drew some initial criticism for glorifying the drug trade, and it is probably this section that is most to blame for that, but I don’t care—I think it’s brilliant, and encapsulates the rich mixture of sound and image that defines Super Fly.

The entire montage sequence is synced to Curtis Mayfield’s “Pusherman”, a song which was written specifically for the film. The whole soundtrack was written and recorded entirely by Mayfield and his band, who feature briefly in the film playing at a club. The soundtrack features two massively popular singles—“Freddie’s Dead” and “Super Fly”—and is widely regarded as a classic. Today, Mayfield’s songs are more popular than the film. It’s undeniable that Mayfield’s work lends itself perfectly to the film and helps to propel it forward. It may even be more crucial to the film than O’Neal’s performance.

They say the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, and that was certainly the case for Gordon Parks Jr. His father was a photographer, musician, and poet who became the first African-American filmmaker to direct a film for a major studio (The Learning Tree). He also made Shaft. The next year, Gordon Parks Jr. made Super Fly. There are some clear signs of his inexperience here, but his shabby, unpolished tendencies lend themselves to the raw story.

Ron O’Neal is charismatic as the impeccably named Youngblood Priest. Curtis Mayfield’s soundtrack of soul and funk is an all-time great. Gordon Parks’ rough and grainy direction gives the whole thing a rugged sheen that enhances its stylistic flamboyance while lending a sense of realism to its sordid moments and loose plot. Far from glorifying the drug trade, the message of Super Fly is a positive one, emphasizing man’s ability to change his station by taking responsibility for himself and his actions.

Sources:

Peterson, Maurice. “Ron Was Too Light For Shaft, But…”. The New York Times. 17 September 1972.