“Don’t misconstrue this. I’m not displaying character—just temporary insanity.”

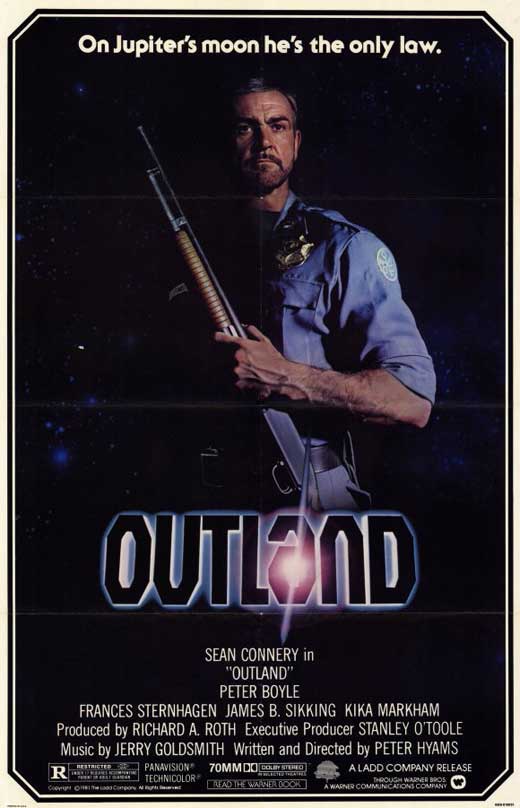

Sadly, the films of Peter Hyams have not endured in pop culture the way those of his contemporaries have. He’s relatively unknown outside of sci-fi circles because he doesn’t have a bona fide classic to his name to act as a gateway to his other work. Though more people have seen (or at least heard of) 2010: The Year We Made Contact, and the tin foil hat crowd appreciates Capricorn One, the director’s most commendable effort is his quintessential space Western Outland. Set within the bowels of a titanium ore mining outpost on the Jovian moon Io, it stars Sean Connery as a Federal Marshall who uncovers a flourishing drug racket that has led to record-setting production rates but a sharp spike in suicides. Drawing on themes and plot beats from classic Westerns like High Noon and Rio Bravo and the industrial space junk aesthetics of Alien, Outland features strong performances from its lead and supporting cast, a tight script packed with witty dialogue, and exquisite set design. Unjustly unsung and overlooked, this gritty tale of addiction and moral compromise deserves a larger audience.

A virtuous man with a strong sense of duty, William T. O’Niel (Connery) finds himself assigned to a yearlong stint at Con-Am 27, where Mark Sheppard (Peter Boyle) works his men hard but rewards them with substantial bonuses and a blind eye turned to their sordid pastimes. Abandoned by his wife and son who are tired of living in cramped quarters and breathing recycled air, O’Niel approaches his new role with righteous determination. After two men die by psychosis-induced suicide—one man pokes a hole in his pressurized suit; another enters an airlock without his suit on1—O’Niel becomes suspicious. Consulting with Dr. Lazarus (Frances Sternhagen), the station’s curmudgeonly dealer of painkillers and sleeping medications, he discovers that the increase in suicides tracks along with the increased production from the titanium mines.

O’Niel’s first true encounter with the sinister effects of the drug occurs when a mine worker shoots up and goes nuts on a company prostitute. In a private room, he beats the girl into submission and then brandishes a knife, which he threatens to use unless… well, he’s psychotic so it’s unclear. In his most authoritative voice, O’Niel begins assuaging the berserker. He has a technician begin fiddling with the door hydraulics while he sends Sergeant Montone (James Sikking) through the air conditioning duct with a shotgun. When Montone jumps the gun and blasts a hole through the addict’s chest without a moment’s hesitation, precluding the opportunity to interrogate the psycho, O’Niel realizes that his second-in-command is in on the scheme.

One of the areas where Outland excels is its integration of world building and plot. The gainful employment of prostitutes shows a potential future in which the occupation is made legal and where a predominantly male workforce is desperate and overworked to a degree that renders the stigma against such sexual activity nonexistent. Likewise, the strip club that serves as the workers’ main hangout and the nonchalant use of hard drugs in the bunk rooms emphasizes the hard lifestyle and moral depravity of the employees. In a similar way, Hyams (who wrote the screenplay) puts O’Niel and Montone on the racquetball court together to remind us that these men lack an outlet for their physical energy. This also serves his purpose of isolating the pair so that O’Niel can confront Montone, which he does by interrupting their game and simply asking, “How deep are you in?” In another extraneous detail, when O’Niel approaches Sheppard’s office to confront him, the honcho is found practicing his golf putt, and later shifts to a virtual driving range.

Allies and suspects begin dropping like flies, but then O’Niel intercepts a video message from Sheppard to his superiors, requesting hitmen and assuring them that the rest of the deputies would step aside for the right price. Out of friends, O’Niel reluctantly accepts the help of Dr. Lazarus. The pair’s relationship is a highlight, marked by savage jokes and biting sarcasm, but in the final analysis, built on mutual respect for the integrity and skill that each brings to their chosen profession. Notably, because Hyams wrote the character as a man and then switched the gender without changing any dialogue, there is not a hint of sexual advance. Lazarus also provides O’Niel an opportunity to vent his frustration with the situation he inherited. Later, Connery displays even greater emotional range when he finally reconnects with his wife and son on a video call (unfortunately, the actor who plays his son is entirely unconvincing).

There’s a whole machine that works because everybody does what they’re supposed to. And I found out I was supposed to be something I didn’t like. That’s what’s in the program. That’s my rotten little part, in the rotten machine.

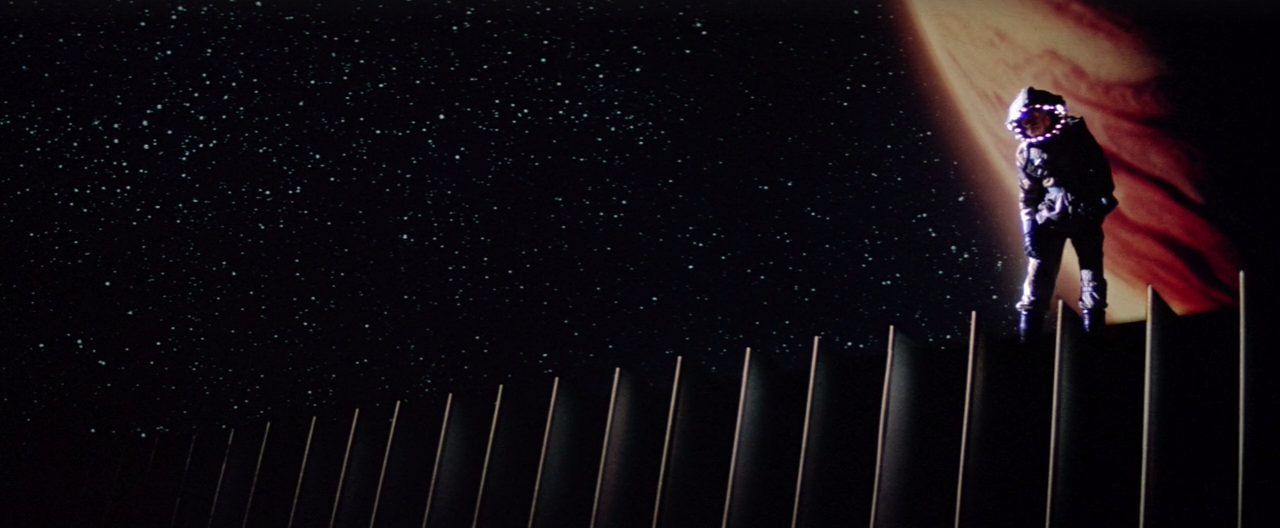

The action may be a little too light for contemporary crowds, though the dramatic score from Jerry Goldsmith and ace editing from Stuart Baird keep things from ever slowing down too much. But a lack of action is only a legitimate complaint if a film isn’t up to snuff in other areas. Outland decidedly is up to snuff, and I think that the verisimilitude of the station covers up almost any flaw that it may have. Hyams denies taking inspiration from Alien, though it seems undeniable. Instead, he cites historical frontier industries like the Panama Canal, the Alaskan pipeline, and oil rigs as inspiration for sketching out a feasible future enterprise, one that was near enough to have knowable limitations and thus avoid entering the realm of fantasy. The use of miniatures works flawlessly, but the innards of the ship are where the production design really shines. With dozens, maybe hundreds of extras just milling about, idling in the living quarters with their cramped bunks, nudie mags, needles, and poker games. Another element that holds up remarkably well is the explicit entertainment found in the club. Beneath pulsing conical blue lights, nude dancers in body paint mime sexually explicit acts while trashy electronica blares through the speakers.

Also worth highlighting is the innovative use of a technique called Introvision, developed by stage magician and hypnotist John Eppolito. The technique used mirrors and mattes to allow actors on an empty stage to interact with a projected environment. Since all the effects were rendered on camera, it eliminated the extensive processing of other techniques and allowed those shots to be incorporated into the rough cut as soon as they were completed. Unfortunately, Introvision never gained a strong foothold in the industry and folded shortly after their work on Army of Darkness. Like many such innovative filmmaking methods, it’s been pushed out by digital effects.

Except for the dated computer interfaces, Outland has aged gracefully. With evergreen themes of corporate greed and the expendability of blue collar workers, a tight screenplay and assured direction, a brilliantly realized setting, and a cluster of strong performances from the likes of Connery and Sternhagen, Outland should be appointment viewing for any fan of vintage science fiction.

1. Now, just because Hyams places his story in a near-future scientifically feasible setting does not mean he’s a hardliner. He’s perfectly willing to bend the rules for dramatic effect, like having heads explode in the vacuum of space (in reality, I’m pretty sure you’d suffocate or freeze to death), or playing fast and loose with the gravitational physics in effect on Io.