“I wouldn’t wish this rotten life off on a one-eyed ferret with mange.”

It is amazing that it took the big old movie-making machine a whopping twelve years to release a sequel to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. In between the first and second films, Friday the 13th had debuted and spawned five sequels, and Halloween had been followed by two. Even Hitchcock’s Psycho, another noted shifter of the horror cinema zeitgeist, had seen a follow-up. By the time The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 hit theaters, the slasher genre that the original had helped create had fallen out of prominence.

The reason that so many sequel-ready fans were deprived of a follow-up is an interesting rabbit hole to stick one’s nose into. Bryanston Distributing, the company that gave the original its wide release, had gone bankrupt, stemming from the fact that they were literally owned by a Mafia family and got involved in litigation over the pornographic Deep Throat. Not only did they fail to pay the filmmakers and cast of the original Massacre more than peanuts, their demise also led to the ownership rights falling into legal ambiguity. That situation took over a decade to settle, with Cannon eventually securing the rights, rehiring Tobe Hooper, and letting him have at it.

If one can look past the outright perversion of the backwoods cannibal horrors of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, there’s a surprising amount of subtext lurking beneath the surface. Vietnam, vegetarianism, mechanization, hippie culture, Southern hospitality—all of it can be found in the crosshairs to varying degrees. If you squint a little bit more, though, you can even detect a black-as-sin gallows humor alongside the unsentimental depiction of evil. This thread of black comedy becomes more evident the more times you see the film, which means many people never pick up on it. In the years after its release, literal hundreds of films came out that overlaid the violent, twisted core of films like Massacre with overt comedy, dressing up absurd encounters with excessive gore and outrageous antics for macabre amusement. It was this mode of tongue-in-cheek self-parody that Hooper adopted when crafting his sequel, and he fails pretty badly.

Unfortunately, rather than moving in a new direction with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, Hooper does a complete 180° turn from the original. Or maybe we’re talking 3D and he took a 90° nosedive straight into the ground. It appears to be more of a spoof than a sequel, and feels like it was made by an industry cynic.

The first problem with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is that it’s a follow-up to one of the most harrowing films of the 1970s. The original had already aged into cult status and was probably impossible to top. So Hooper decided not to try—even though he tried often enough with his non-Texas Chainsaw films—and pivoted to low-brow comedy instead. It doesn’t evoke the choking laughter that can be found in the original, but a vague kind of amusement one gets from watching a child misbehave (and the same gradual lessening of that amusement the longer it continues). The second issue is that Hooper had spent the previous decade making punishing horror films (excepting Poltergeist, which many claim Spielberg actually directed—which probably didn’t help Hooper’s attitude) and had no experience directing comedy. Also ill-suited to his task was screenwriter L.M. Kit Carson, whose most recent work at the time—impossible as this sounds—was Paris, Texas. This was a recipe for disaster. The concept of a funny sequel to a serious horror film isn’t necessarily a bad one, but we’re not discussing the abstract here. I’ve seen the film, and it’s not good. The wackiness meter is cranked way up, but there’s no attempt to make it work as a horror film, rendering its gore and shallow jokes ineffectual.

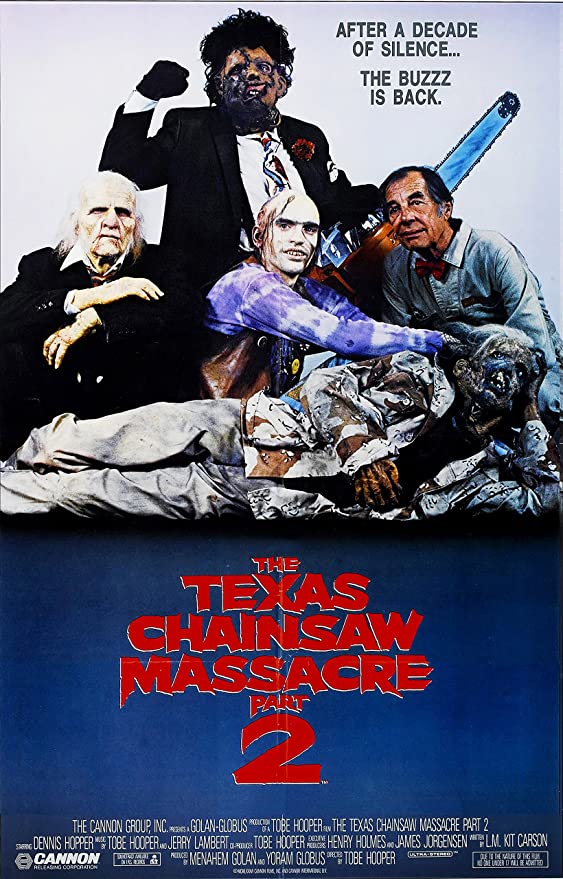

It is perhaps too easy to chalk up this dud as a failed comeback attempt by Hooper, a desperate grasp at relevance by a former one-hit wonder. He seems to try and fail to implement the latest trends of the genre while throwing subtlety out the window and presenting us with shock value as entertainment. He’s seemingly forgotten so many things that came naturally to him a decade prior. Out is the gritty realism and the careful aesthetic of implied violence. In its place is an opening scene of Leatherface (Bill Johnson) standing on the back of a moving pickup truck and sawing the head off of an inebriated young man—the remnants of which squirt gallons of blood. Out is the terrible menace of Leatherface’s unpredictable inhumanity. In its place is a manchild whose chainsaw is a stand-in for his manhood. The young man who lost his head had called into a local radio station just as the ordeal began, and the deejay, Stretch (Caroline Williams), caught the whole thing on tape. Lieutenant “Lefty” Boude (Dennis Hopper), uncle to Franklin and Sally Hardesty from the first film, has been on the prowl all these years, searching for signs of his niece and nephew and tracking the news of chainsaw murders. Stretch serves as our requisite scream queen and the source of amusement and sexual confusion for Leatherface. Lefty provides Dennis Hopper a chance to dual wield chainsaws and yell “I’m the Lord of the Harvest!” On a surface level, it’s pure camp.

When Stretch plays the “death tape” over the radio in order to help Lefty’s pursuit of the Sawyers gain some public traction, Drayton (Jim Siedow, the only returning cast member) sics his boys Leatherface and Chop Top (Bill Moseley) on her. They kill and skin her producer L.G. (Lou Perryman), but Leatherface has the hots for her and decides to let her live for now. She soon ends up in a tedious reprise of the dinner scene from the original—complete with Grandpa Sawyer and a hammer—this time interrupted by Lefty and his double chainsaws.

It’s an incredibly empty-headed script, and the only scene that is genuinely funny is when Lefty is testing out a variety of chainsaws like a madman and the proprietor says to himself, “Oh my achin’ banana.” Once we arrive in the bowels of an abandoned amusement park that serves as the Sawyer’s home, the film’s stylistically clashing elements merge into an incredibly awkward half hour. To put a cap on the sequel’s complete subversion of the first film, the sequel ends with Stretch triumphantly dancing around with a chainsaw in the same way that Leatherface did at the end of the original.

Like I said, it’s easy to rip Massacre 2. It is more challenging (but debatably correct) to find partial redemption for the film by viewing it through the lens of Hopper’s disillusionment with a harsh industry. In other words, to read it as satire. To consider Drayton Sawyer’s award-winning chili and its “prime meat” not as a mere gross-out, but as a comment on the genre’s penchant for handsome young casts and high body counts. To view Leatherface’s infatuation not as mere sexualization of Stretch but a depiction of repressed sexuality. To try to find some heretofore undiscovered depth in the character of Chop Top, who spends most of his time on screen shouting about Vietnam and picking at his metal scalp with a coat hanger and eating whatever he scrapes off. To mount that kind of defense requires some real passion for a mediocre film, and Massacre 2 simply doesn’t inspire that from me, so I’ll leave the impassioned pleas to someone else. But the potential is there and I know some people really love this.

But I think it’s fair to say that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 is only relatively bad. It’s still ultimately serviceable and works just as well as many of the other mediocre horror-comedies from the 1980s. Tom Savini’s effects work is great, and Hooper’s aesthetic eye is mostly good. But it’s just joyless to watch, with only a few brief glimmers of fun to be found, and very little horror actual horror. It could have been forgotten, but instead the pain of its failure lingers because it took such an iconic film and crapped all over it.