“I’d like to be reborn as a demon. I’d be reborn in hell anyway, and demons have it easier there.”

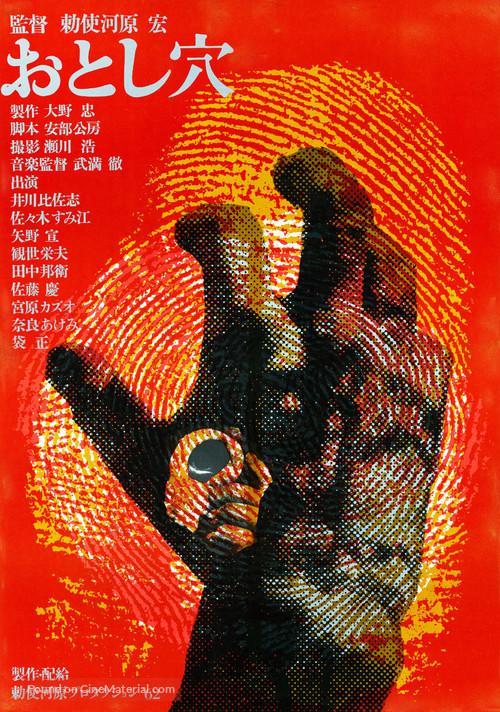

Pitfall is the feature debut of Hiroshi Teshigahara and his first collaboration with novelist Kōbō Abe (author of Inter Ice Age 4). Teshigahara occasionally finds himself as a footnote in cineaste circles. With the release of his second film, Woman in the Dunes (also written by Abe) he became the first director of Asian descent to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director. But his wider body of work is not well known at all in the West. A big thanks to the Criterion Collection who, at least for a time, packaged three of his early films together in a box set.1 Also included in that set are some of Teshigaraha’s early documentary films which really help to clarify the interesting genre-blend of Pitfall.

While Pitfall isn’t as good as Teshigahara and Abe’s further collaborations, it is still a very smartly made film. In consideration of the surrealist tone, the black comedy, and the eerie ghost story backdroping the main crime drama narrative, many reviewers like to refer to the film as “Kafkaesque.” I tend to agree to a certain extent—there are a lot of clues thrown at us, but a decided lack of context. And by the film’s conclusion, there is no apparent way to coherently piece together what we’ve seen. Framed by a power struggle between rival bosses, the film also bombards the viewer with elements of horror, documentary, and crime drama in an intriguing if not entirely compelling amalgamation of storytelling types. Regrettably I found that once I had seen the film I preferred my idea of it, which was based on its written description, to the thing itself.

Pitfall is characterized less by its scenery of coal piles and dilapidated shacks than by its host of shady characters. The first one we meet, and our ostensible main character, is an unnamed coal miner (Hisashi Igawa) who has quit his job in search of a new opportunity. He wanders to an unfamiliar village with his young son where he finds employment. Mysteriously, his new boss gives him a special task almost immediately, trusting him with an important trip out into the countryside. He chalks it up to good luck, but soon finds himself in trouble when he arrives at the town and finds it abandoned. In a deserted field, he is knifed to death by The Man in the White Suit (Kunie Tanaka), a peculiarly-mannered and highly stylized gangster who had been following and photographing him for some time. This crime has only two witnesses—the man’s son, who will go on to observe nearly every sordid deed that the audience sees, and a local woman who owns a candy store. The crime initially seems limited in scope—a hit pulled off by a professional—but it soon reveals a larger conflict that is occurring on the periphery of the film. This overarching power struggle remains largely invisible to us, with only the movement, capture, and discussion of pawns as evidence of its existence.

Given only glimpses, our impressions cannot add up to a concrete explanation of this larger conflict. This is fine, though, because there is more to grapple with. Namely, the ghost story. Soon after bleeding out in the marsh flat, the unnamed miner is resurrected, floating up onto his feet in a new body while his corpse remains. At this point, Pitfall takes on a fresh, surrealist tone. Not only does our unconventional protagonist leave his own body lying in the mud, but as he lurks about the countryside in search of answers, he discovers his own doppelgänger. This expands into several cases of mistaken identity, in both the material and spirit worlds. While this angle could have been pushed into explorative territory, it’s mostly used for some offbeat comedy that I didn’t find very compelling.

The man continues to wander around, hoping his luck will turn, endlessly seeking to make sense of his own life and death. Only the audience and other ghosts can hear him. In one scene, while poking his nose around the formal police investigation, he finds himself face to face with a man whose neck is craned all out of whack—it turns out he had been the unfortunate victim of a cave-in. He informs our dead miner that, as a ghost, he will remain eternally in the same physical condition as when he died. Meaning that our dead miner, who is hungry, will remain forever so.

This search for self-knowledge and understanding of oneself, stabbed at by the amateur ghost story and the instances of mistaken identity, is not fleshed out in Pitfall to the degree necessary to make it interesting. The more bizarre wrinkles, while present, are quickly turned away from, whereas in Teshigahara and Abe’s subsequent films together these existentialist themes are fleshed out and explored in a much more fulfilling manner. As a pitiful man resurrected as a pitiful ghost, the dead miner provides none of the philosophizing or questioning that makes those later films so meaty. Rather, he simply wants to know why he was singled out and killed. Without a strong main character to pull things together for us, our attempts to assemble these clues into something with meaning are for naught. There appears to be nothing more here than the admittedly very nice camerawork and the general themes,2 which together make for a good looking and interesting film but one that is easily forgotten.

Silent throughout the entire film is the dead man’s son. He witnesses his father’s murder, the rape of the candy store owner, her murder, and the list goes on. I don’t quite know what he is meant to mean to us. He displays a certain tact that the adults around him lack. He fends for himself, catching a frog and using it to lure larger game; he creates figures out clay to entertain himself. Perhaps his character has something to do with the loss of innocence as we mature, as he acts as a direct counterweight to his father, who blames his shortcomings on everyone but himself, hopeful that his fortune will be stumbled upon rather than earned.

1. Woman in the Dunes and The Face of Another are also in the set, along with a supplemental disc. Unfortunately, the set is now out of print and worth way more than I paid for it.

2. To my understanding, part of what Teshigahara was going for here was to tackle a social issue (coal mining conditions) through the lens of myth and folklore. Maybe I’m just lazy, but I’m not inclined to read up on mining conditions in 1960s Japan to try to glean some allegory from this. I think the peculiar mixture of genres and styles suffice to make it interesting enough to watch and I’m not sure that a localized allegory would really have any sort of impact on someone so far removed from its inspiration.