“They are attracted to the one thing about her that is different from themselves—her life force. It is very strong. It gives off its own illumination. It is a light that implies life and memory of love and home and earthly pleasures, something they desperately desire but can’t have anymore.”

A discussion of Poltergeist must, as a matter of course, be framed by the question of its authorship. Just as Steven Spielberg’s admiration of Piranha led to a collaboration with Joe Dante on Gremlins, so his affection for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Funhouse led to his teaming up with Tobe Hooper for a modern haunted house movie. But where Dante’s project fits snugly into his oeuvre, Hooper’s looks and feels like a mid-tier Spielberg picture with only occasional hints of Hooper’s grindhouse shlock—a reality that has led to an ongoing debate over who truly directed the film.

In one corner you have Spielberg fanatics arguing that Hooper was nothing more than a stand-in that allowed Spielberg to work around his restricting contract with Universal (which forbade him from personally directing another film while E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was in production). In the other you’ve got miffed Hooper defenders who are reluctant to let go of a seminal ‘80s horror film for a director who seldom achieved popular success.

Firsthand accounts differ on the level of Spielberg’s involvement beyond penning the screenplay and producing, with various anecdotes indicating that he exerted creative control over storyboarding, supervised special effects, offered on-set guidance to Hooper, and reset shots to his liking—stuff that a typical screenwriter or producer doesn’t do, but who’s going to turn down creative instruction from Steven Spielberg? Who’s going to overrule him when he makes a suggestion? Others, including many cast members, assert that Hooper was the one on set, blocking scenes and working with the cast and crew. In the end, though, it’s quite clear that the creation of Poltergeist was a collaborative effort. It’s tinged with Spielberg’s tendencies toward family dynamics, contemporary suburban life, and narrative warmth because he wrote it, and darkened by Hooper’s slimy violence and shock horror because he was the workhorse calling the shots on a daily basis. It seems obvious to me that Hooper wouldn’t have naturally crafted a sentimental supernatural thriller on his own. But then neither would Spielberg have made a film quite as disgusting as what we see here, nor would he have elected for a madcap double climax that involves an animated clown doll strangling a child.

The resulting concoction is a melting pot of ideas that never quite congeals into anything coherent but is all sorts of campy fun—a somewhat family friendly take on horror that’s only made occasionally spooky by excellent effects work and Hooper’s penchant for splatter. Indeed, Spielberg’s fingerprints are most apparent when Poltergeist is at its least threatening.

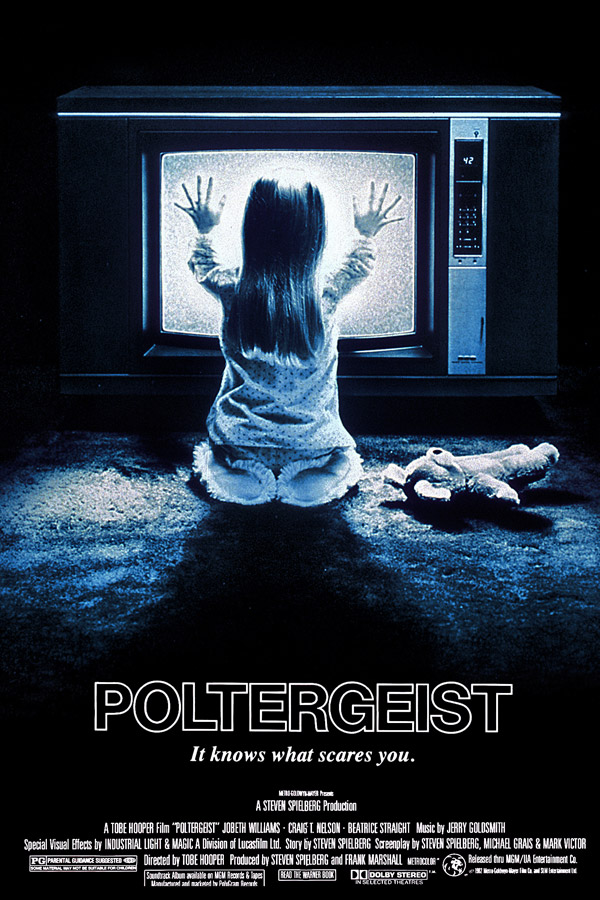

The film opens with thirty minutes or so that amount to a brilliant time capsule of the 1980s suburbia: neighborhood kids racing RC cars; bedrooms lined with Star Wars memorabilia and other pop culture bric-a-brac; neighbors accidentally changing one another’s television channels; stations that stop broadcasting overnight, causing the screen to emit white noise. It’s this last bit that Spielberg uses as his gateway to the spirit world, suggesting something (although I’m not sure what exactly) about the unhealthy connection that children form with television by having a young girl communicate with ghosts through the impenetrable static that flickers at her sleeping family.

This is all firmly within Spielberg’s wheelhouse as the film economically establishes the familiarity of the suburban setting and the dynamics of the Freeling family. Steven (Craig T. Nelson) and Diane (JoBeth Williams) Freeling are run-of-the-mill middle-class parents living in a planned community in California with their three children, Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke), Dana (Dominique Dunne), and Robbie (Oliver Robins). Steven’s a sales rep for the company that has built the development they live in, the kind of mildly ambitious fellow who is willing to skim-read Ronald Regan’s biography before bed but unwilling to take any real risks in his career. Diane is a bit more free-spirited, covertly smoking weed in the bedroom after the kids are asleep, laughing at her husband’s goofy antics, and reminiscing about his glory days when his mind was a little more open and his belly a little less prominent.

After a series of tension-building teases—a milk glass shattering at random, eating utensils bending, chairs stacking themselves on top of the dining room table, all of which are accepted as an amusing paranormal sideshow by Diane—the Freelings’ world is turned upside down when Carol Anne summons a legion of ghosts through the scrambled pixels of their bedroom television set and is herself sucked into the netherworld through a portal. All that remains is her disembodied voice calling out from somewhere in the house, forcing the family to remain on the premises despite the otherworldly manifestations.

I would love to say that Spielberg’s screenplay builds on this solid setup and that once Poltergeist unleashes its blitz of scares it comes together in a satisfying way. But it doesn’t. Instead, it turns into an extravaganza of special effects, each scene trying to one-up the one before it with additional gristle and gore. Spielberg has occasionally utilized some shocking effects—melting Nazi faces anyone?—but the visceral imagery in Poltergeist is much more overtly shocking than one expects to see from him. And thus we must conclude that this portion of the film is the work of Hooper. A clown doll coming to life and attacking a child, a demon-possessed steak squirming its way across the kitchen counter, skeletons floating around in the murky water of an unfinished pool that happens to sit atop an old cemetery—these feel like the work of a man who made grindhouse films about cannibals. So do several later scenes, one involving Diane luxuriating in a bubble bath, another featuring the frantic mother fending off monsters while clad only in her panties and a t-shirt like the cover of a trashy pulp horror novel.

However, if we need incontrovertible proof that Hooper asserted himself in the making of Poltergeist, look no further than the sequence in which a paranormal researcher hallucinates himself clawing his own face off; a scene which, oddly enough, is said to feature Spielberg’s hands ripping and tearing at the latex and slime. These highlight sequences are surrounded by an abundance of other effects—goo leaking around doorways, rooms that spin and toss their inhabitants onto the ceiling, closets that suck up everything in the room like a jet engine, ghostly tendrils emanating from shadows, six foot demon heads.

The plot’s resolution is completely silly. However, if you realize early on that this is the type of film that flirts with danger but is ultimately safe, you can latch onto the campy undertones and enjoy it for what it is. To wit, after a “doctor of parapsychology” (Beatrice Straight) fails to rescue Carol Anne (and nearly drags the film to a standstill with her lifeless speeches), there’s an extended sequence featuring a clairvoyant medium named Tangina (Zelda Rubinstein) who stands barely four feet tall and speaks in a childlike voice. She delivers ridiculous monologues with conviction and initiates a simplistic rescue plan that involves tennis balls and a coil of rope.

It’s not remotely scary but it has enough bite from Hooper and enough movie magic from Spielberg to make it a pleasurably spooky experience.