“My girlfriend shouldn’t be a hooker.”

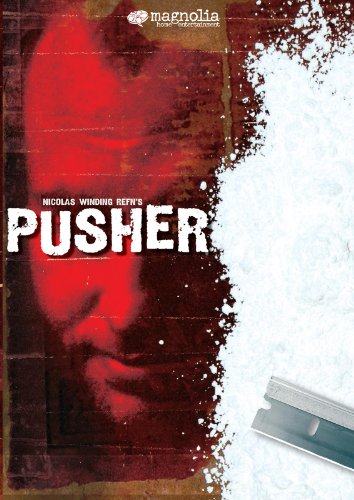

Pusher, the galvanizing debut from Nicolas Winding Refn, initially feels like an indie film cut from the same cloth as Tarantino’s stylish genre remixes. Marked by long-winded conversations and sly humor, laced with drug use and brief moments of extreme violence, it sounds similar enough on paper, but on the screen it evolves into something far less transparent and far less comfortable, something more akin to Mean Streets or The Killing of a Chinese Bookie than to Pulp Fiction.

Writer/director Refn lines the grimy streets of his native Copenhagen with lowlifes, deviants, thugs, and prostitutes, many of them characterized less by their disreputable trades than by their quirks and ambitions. In this milieu he locates Frank (Kim Bodnia) and his nihilistic wingman Tonny (Mads Mikkelsen), two low-level hoods who careen around the locale slinging dope, trading fabricated stories of their sexual bravado, and profaning themselves. When a large heroin deal goes bad, Frank finds himself returning to his supplier (Zlatko Burić)—an aspiring restaurateur who operates out of a cheap diner—sans money or product. To make ends meet, and quickly, Frank pinballs around the city, resorting to all manner of pitifully desperate measures as he tries to scrounge up enough money to buy his life. He visits neon clubs, dilapidated crack houses, dingy bars, and even his own mother’s house, all the while selling, trading, bargaining, strong-arming, threatening; anything to survive.

The real selling point here is Refn’s handheld camerawork, which renders the pair’s exploits unsettling with all its jitters and jerks and its kinetic, over-the-shoulder vantage. Though the compositions are deliberate with their busyness and movement, there’s no glamorization of the gangster lifestyle. Bodnia’s Frank is a no-nonsense operator—his masculine demeanor gradually giving way to animal fear as his options dwindle—and the camera captures his increasingly violent exploits with a shocking immediacy. A scene in which he takes a bat to a friend that he suspects ratted him out offers a stunning sense of realism.

Frank is the poster child of the theme, but one gets the sense throughout the film that whatever lofty ambitions these underbelly denizens might harbor, there’s no escape, no forgiveness—only quicker and slower avenues to the same endpoint.