“Stay away from anything and everything these little midget Ali Babas give you, alright?”

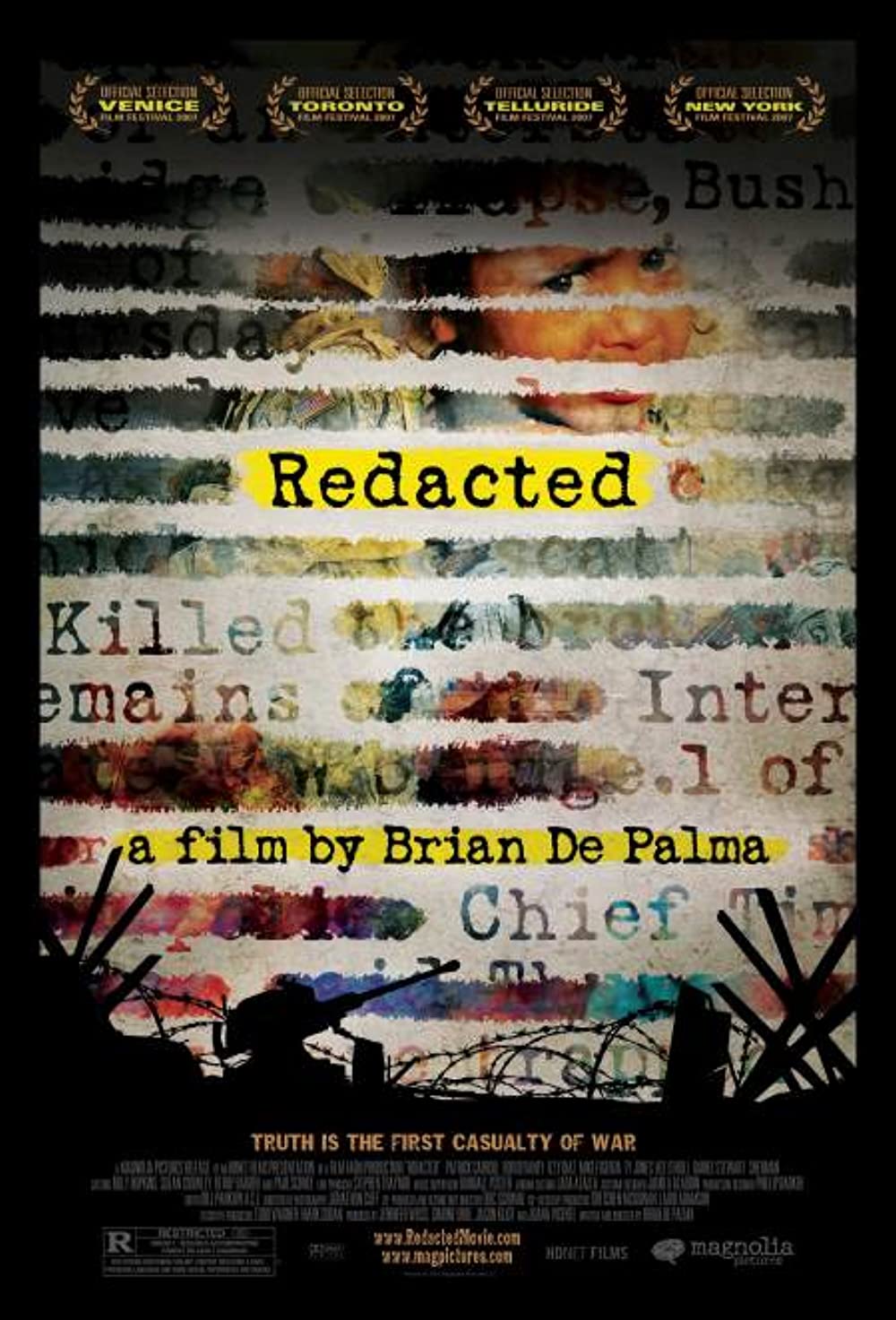

Brian De Palma’s Redacted revisits subject matter that the filmmaker had explored in Casualties of War—namely, the rape and murder of innocent civilians at the hands of American soldiers. Both films are based on true stories, but where the earlier film took the standard Hollywood approach with its conventional narrative and prominent movie stars, Redacted presents itself as a found footage antistory, devoid of structure and populated with unfamiliar faces, pervaded by graphic violence and unchecked hedonism. It’s a boldly executed experiment of middling success, meant less for enjoyment than to spark conversation.

It opens by informing us that, although the film itself is fictional, the events depicted really happened. We read this from a short paragraph of text that is gradually blotted out with black ink after we’ve had a chance to read it in full, the unseen editor first removing the two instances of the word “fictional.” The short version of what actually happened is that a small group of U.S. soldiers on tour in Iraq gang-raped and killed a fourteen year old girl, then murdered her parents and younger sister as well. The heinous details of this crime are recreated here with shaky cam realism, as is the beheading of a soldier who is captured and killed by insurgents in retaliation.

But De Palma seems less interested in the shock of the crime for its own sake than in using it to examine the sanitized war reporting that traverses the airwaves and informs the citizenry back home (hence the title). To force us to examine our relationship to technology and media. In order to achieve this, he employs a clever setup that involves multiple audio-visual points of view. The most prominent is the handheld camera of Salazar (Izzy Diaz), a private who has enlisted in order to secure government funding for film school. He carries his camcorder with him at all times with the aim of capturing raw footage that he can turn into an acceptance letter. Although his intentions seem benign, an early confrontation with a reclusive bunkmate (Kel O’Neill) alights on De Palma’s primary preoccupation: does the camera tell only the truth, only lies, or some combination of the two? This calls to mind a monologue in David Holzman’s Diary, wherein a character opines that the camera’s mere presence fundamentally alters its subjects’ actions and thus it cannot be viewed as a truth-capturing device. Later, Salazar finds himself in extremely dicey territory when he decides to record the rape instead of leaving or intervening. Might the filmmaker-soldier have chosen a more virtuous course of action had he not felt compelled by a self-generated need to document the wicked act?

Elsewhere we find a French film crew making a rose-tinted documentary about the soldiers manning a traffic checkpoint (complete with classical music), newscasts from a fabricated Arabic channel, online vlogs from a soldier’s wife and a terrorist sect, and CCTV footage from inside the base. In effect, De Palma is launching an assault on the weird reality of news media, suggesting that there’s very little appetite for the unadulterated truth, but an endless demand for a synthetic supply. Moreover, because the news has gradually devolved into a respectable version of reality television even as it has become ubiquitous, war reporting has become just another flavor of content that barely registers. Palatable atrocities are now commonplace, even if their immediacy is often feigned. This actuality is underscored by a photo montage coda that depicts “collateral damage” of military action—mutilated children, gutshot pregnant women, &c. Amongst this raggedy patchwork of unreliable viewpoints sits De Palma, voyeur par excellence, asking us to question the way that we look at things. Though accounts differ, it’s interesting to note that many of the faces in these photographs have been blacked out against the director’s wishes; i.e. Redacted was itself redacted.

It’s a dog and pony show for the folks back home, right? I’m just one of those bad apples, huh?

Unfortunately, outside of this media commentary, which is more of an intellectual exercise than a cinematic experience, Redacted is more or less a disaster. It tries to be verisimilitudinous with its amateur camerawork but then stuffs its characters’ mouths with hamfisted dialogue. It tries to be anti-war but portrays its evildoers (Daniel Stewart Sherman, Patrick Carroll) as exaggerated cartoon villains. It tries to tell the truth but leaves out pertinent details that conflict with its message. Look, I’m not particularly keen on sending soldiers overseas to engage in endless wars. But Redacted is less effective at making war seem inherently wrong or American soldiers particularly incompetent/sadistic/perverted/racist than it is at reinforcing the notion that total depravity is the default state of mankind. Which is perhaps a more profound insight. Certain political pundits disliked the film because of its perceived anti-American message, but it’s just as valid to dislike it because it’s poorly made.