“Your life is not a very good script. But somehow I don’t think that you want to make a good movie. What you want to do is try and think about your life, find out the truth. There’s something that happens that you don’t understand, you want to get to the core of it.”

David Holzman (L.M. Kit Carson) is a firm believer in the transcendent properties of cinema. The walls of his tiny NYC apartment are crowded with movie posters and other mass-produced bric-a-brac related to his favorite films. He’s adopted the philosophies of his idols—Hitchcock, Welles, Powell, but most importantly, Truffaut and Godard—as his own, and has decided, in wake of his recent loss of job, to search for the ultimate truth by testing Godard’s maxim: “cinema is truth at 24 frames per second.” He believes that immortalizing his own life on celluloid will help him to pin down the elusive secrets of the world that have been slipping through his fingers, to bring the mysteries into focus.

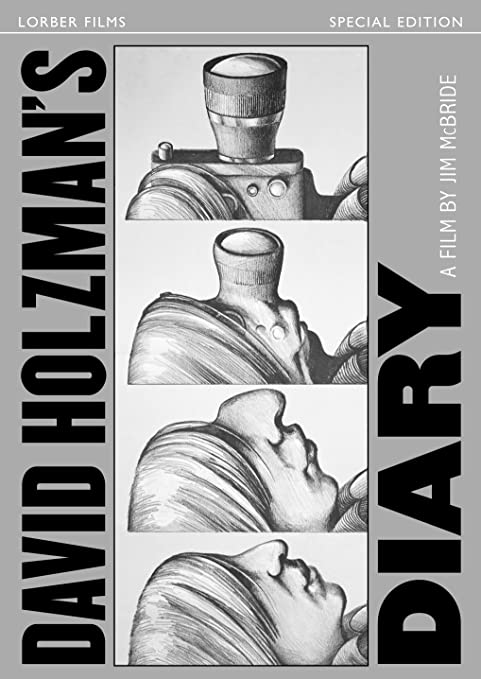

In July of 1967, one day after becoming eligible for the draft, he begins making a video diary with his well-loved filmmaking gear: a 16mm Éclair camera, a Nagra tape deck, and a Lavalier microphone—sufficiently portable to allow their sole operator to maneuver the streets of New York and make a documentary of his own mundane life. The problem, which takes only a few days to emerge, is that making his life into a film fundamentally alters it. This realization comes only after he’s driven away his girlfriend Penny (Eileen Dietz) by filming her in her sleep and trained his camera on his friend Pepe (Lorenzo Mans), who encourages him to halt his project because “as soon as you start filming something, whatever happens in front of the camera isn’t reality anymore. […] Decisions stop being moral and start being aesthetical.” By the end of a week David has grasped no euphoric truths, but has thoroughly confused himself and alienated his closest friends.

While presented as a documentary until the end credits reveal the layers of its artifice, David Holzman’s Diary is, in fact, one of the first examples of a mockumentary. Coming at a time when other film movements were exploring the uncertain relationship between reality and the camera (direct cinema, free cinema, cinéma vérité, docudrama, etc.), Jim McBride’s first project refracts that overriding concern through a darkly humorous lens. Cutting through the pretensions of those sophisticated schools of thought, the film posits that cinema has an observer effect—that capturing “reality” on camera is a fool’s errand because the very presence of the thing alters the behavior of its subject. Case in point is Pepe’s minutes-long monologue, which would have remained unspoken, maybe even unthought, if David’s camera had been absent.

Pepe’s assertions are not isolated to his speech but upheld by the entire film, which sees David progressively detached from reality and cut off from genuine human connection. Frustrated that his diaries haven’t brought the world into focus, David begins experimenting with odd angles and fisheye lenses and montage and silence and blank screens and voiceover narration and slow motion, attempting to overcome his failure to understand reality by changing its shape.

Holzman, perhaps over-informed by the cinema, is no amateur when it comes to filmmaking. Sure, there’s a roughness to his footage, owing as much to his handheld rig and solo setup as the actual film’s guerilla production, but he’s certainly informed by his role models of the French New Wave, in addition to underground American filmmakers (Cassavetes, Mekas) and contemporary documentarians (Pennebaker, the Maysles brothers). In amongst his people-watching and vlog-like conversations with the camera, he captures the texture of city life: the way apartment windows reflect light as he moves past atop an open-air bus; the way the senior citizens on a long park bench either perk up or don’t when he whips the camera by their faces in an extended tracking shot; the habitual mannerisms of a neighbor (Louise Levine).

The film is not always gripping in the trenches, as its format and conceits lead to long stretches of unglamorous activity, often captured in long takes. About as immediately exciting as things get is when David briefly follows a stranger he observes on a subway (Fern McBride) or when he has a conversation with a chain-smoking transsexual who senses an opportunity to star in a homemade porno. But it’s in these prosaic grooves that the film provokes thoughts about the art and artifice of filmmaking. The further David progresses in his project, the more obsessed he becomes, even as its utility as a truth-seeking device diminishes. What began as casual voyeurism and fantasies about a neighbor turn into outright stalking. He grows so uninterested in the beats of his own life that he resorts to a rapid-fire montage of his evening of television watching (technically we see everything he saw, but it would be so brain-numbing to relive it that it must be sped up). But, circling back to Pepe’s point, if the camera had never started rolling, Penny would still be spending her evenings at David’s place, and so he wouldn’t have been watching television alone. Nor would he feel the need to resort to onanism.

It turns into one of those vicious, self-perpetuating cycles. David begins as a giddy cinephile, but once he begins filming, he realizes that his life is quite banal. And so he focuses even harder, because filmmaking is his passion, and producing his video diary is precisely the kind of thing he needs to shake things up. But the further he is sucked into his voyeurism and psychoanalytic confessions, the less capable he becomes of having conventional relationships with other people. In this way, Jim McBride and L.M. Kit Carson predicted the harrowing downsides of reality television, Youtube stardom, and social media celebrity—forms of content production where the constant presence of the individual, rather than a bounded work of art, is the focal point. At the end of the day, few if any people are inherently interesting enough to sustain such unwavering attention and they suffer under that weight. And now that a generation has been raised on smartphones and many of them have become unhealthily attached to their devices, just like David, they are incapable of holding conversations or building relationships. The very tool supposedly designed to foster communication has driven us apart.

Whether Jim McBride intended his film to be quite so prophetic or philosophical is uncertain. Certainly he wanted to hone in on the topics of voyeurism and narcissism and send up his self-serious documentarian contemporaries, but with only $2500 (originally intended to fund a book of interviews on documentary filmmaking) and a five-day shooting window, certain sacrifices had to be made. That those offhand decisions led to a film that feels more prescient and pertinent the further technology advances is an unexpected bonus.