“Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

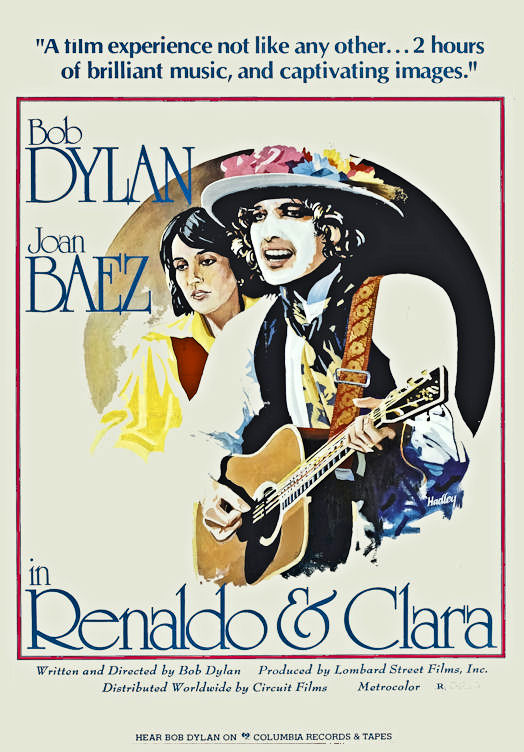

Everybody knows the name of Bob Dylan. Preeminent songwriter, folk-rock pioneer, off-and-on “prophet of the times,” civil rights advocate, self-mythologizer. I don’t need to do a re-run of his achievements here (though I plan to at some point). He’s such a beloved countercultural figure and has been so prolific throughout the decades that it’s kind of funny to realize just how much mediocre material he’s pumped out. Wading through his unfathomably deep discography you’ll inevitably stumble onto some real clunkers. He’s also occasionally branched out into other artistic mediums—painting, books of poetry, autobiography, acting. For his 1975 tour, dubbed The Rolling Thunder Revue, Dylan decided to make an experimental film, one in which he’d play fast and loose with fact and fiction. The uneven and bloated result of that whimsical idea is Renaldo & Clara, a film that works much better on paper than it does on screen.

Clocking in at nearly four hours in length, Renaldo & Clara comes off as an incoherent documentary of the tour. It’s so scattered and sloppy that it’s very hard to discern any structure at all. The improvised, “home video” aesthetic, while occasionally creative, feels pretentious pretty quickly, making four hours a long hard slog. But this is Bob Dylan’s pretentiousness we’re talking about here, and Bob Dylan deserves to be taken seriously as an artist even when he’s at his worst and most self-indulgent. So I forced myself through it if only to say that I had. What I discovered was not that it is bad, but that it fumbles too often in its experiment. It’s the kind of overblown thing that a well-known arthouse director could release to some degree of praise while the vast majority will sneer and call it ridiculous.

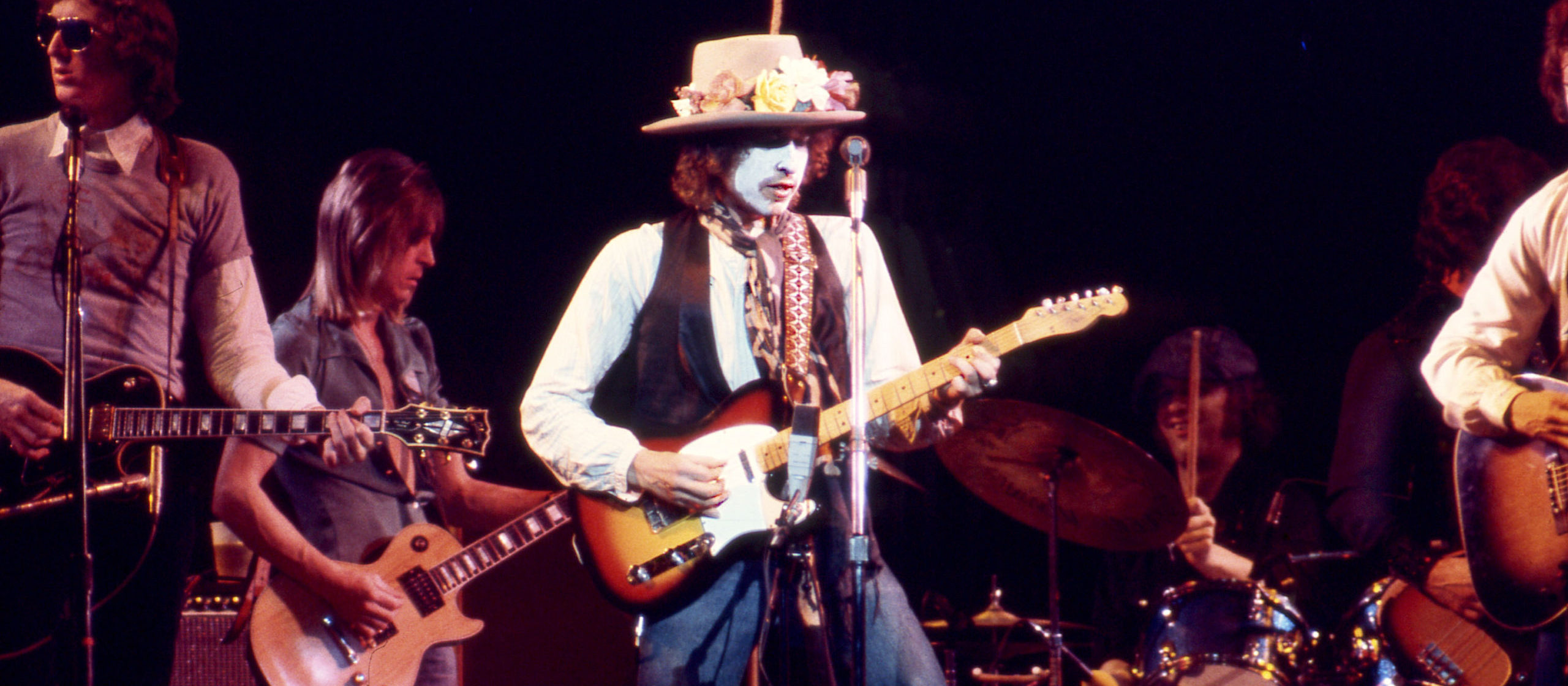

Renaldo & Clara is composed of so many little, disassociated clips that it’s hard to ever get a handle on things. Backstage ramblings, random interviews about politics and the Beat generation, Dylan’s friends and fellow artists monologuing off the cuff, documentary-esque filler, fictional sequences… and concert footage. At the very least, the musical performances are fun and worth the time for a Dylan fan. Everyone who’s casually acquainted with Dylan has seen images or maybe even some footage of him all dressed up with his white face paint on. That was this tour. Captured by intimate handheld camerawork and featuring good sound, we’re treated to performances of ‘Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door’, ‘Isis’, ‘Hurricane’, and ‘Tangled Up in Blue’, among others. The film opens with a rendition of ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’—a personal favorite—performed while Dylan wears a clear plastic face mask.

Even some of the backstage bits are fun deep cuts for the extreme devotee. There are stories of Dylan’s early career in Greenwich Village from old acquaintances, interviews about the wrongful conviction of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, Allen Ginsburg reading poetry and dancing around, David Blue playing pinball and waxing poetic about the enigmatic Dylan, street preachers in fist fights, palm readers, Jack Keroac’s grave, and elements of a fictional rural drama submitted by playwright Sam Shephard at Dylan’s request. (Interestingly, Shephard was working on similarly narratively sparse work with Terrence Malick at the time—Days of Heaven, which happens to be a personal favorite of mine.) Many of these individual segments would be completely usable material in a documentary—and maybe they could have worked here—but Dylan’s editing is incredibly suspect. Sequences cut off abruptly, or begin mid-word, previously used sequences reappear later. It’s like he cut and pasted using some intuitive divining technique that just doesn’t work.

Bob Dylan basically plays himself for most of the film. This makes sense because for most of the shoot he had to be the touring musician Bob Dylan. But at one point Ronnie Hawkins claims to be Bob, and at others Bob claims to be the titular Renaldo. At another point, Dylan’s ex-wife Sara (who is supposed to be Clara) and his frequent collaborator Joan Baez argue over the songwriter’s affections. The members of the “cast,” who were probably just improvising most of the time, uncertain if they were in a documentary or a narrative film, are given ridiculous names in the credits—Joan Baez as Woman in White, Jack Elliott as Longheno de Castro, Harry Dean Stanton as Lafkezio, Bob Neuwirth as The Masked Tortilla, Allen Ginsburg as The Father, Anne Waldman as Sister of Mercy, T-Bone Burnett as The Inner Voice, Sam Shephard as Rodeo.

Consider that Dylan’s never truly been an insider though. He pushed musical boundaries and was called “Judas” by those who didn’t like his innovations. He only enjoys popularity because his musical disruption caught on and was adopted by the mainstream. Many successful acts of the past four or five decades wouldn’t have had the platform or the audience if it weren’t for his 1960s output. So what if his lone attempt at cinema wasn’t palatable for the masses? It’s similar enough to what fellow outsiders like Jonas Mekas were doing that it’s unfair to criticize it because it’s unconventional. It’s not as good as the stuff Mekas was doing, but it’s not bad because of its style. It’s bad because it is constructed poorly and need not have been four hours long.

Like Dylan’s songwriting process, Renaldo & Clara is not composed of logic and rules. He writes what comes into his head, arranges it all on the table, and mixes and matches and juxtaposes. I imagine that’s how he tried to edit. But all those concrete images in the film cannot be subtly changed. They’re not malleable like words and verses and chord progressions. The images he has to work with also didn’t originate in his singular mind, so the magic that he so often comes up with on his own isn’t permeating the whole.

Nevertheless, it’s a peephole into the mind of an enigmatic man. That people can even hear a description of it and want to watch it speaks to how much respect he is given as a creative. I very much prefer the focused songwriting that he is able to draw out of the rugged tapestry of his mind, but I’m not going to turn my nose up when he tries something that isn’t the same old, same old. Renaldo & Clara is not for the casual Dylan fan. It also probably isn’t much use for the student of the avant-garde. If it has a message, it is that everything is performance. It’s way too long for its own good, but partially redeemed by what Dylan does best—play music.