“It is the sworn duty of all officers to try to escape. If they cannot escape, then it is their sworn duty to cause the enemy to use an inordinate number of troops to guard them, and their sworn duty to harass the enemy to the best of their ability.”

As far as I can tell, the only textual connection between The Great Escape and Christmas comes when a handful of prisoners of war hold choir practice to mask the sound of their fellow hopeful escapees’ clandestine labors. And yet for some reason John Sturges’ three-hour epic ensemble piece is traditionally shown on British television around the holidays. Though some have attempted to make sense of this phenomenon from a historical perspective, I think the reason it is popular around Christmastime is quite simple: it embodies the virtues associated with Christmas.

Consider that of the planned two hundred and fifty escapees, a miscalculation in distance means only seventy-six make it out of the Nazi P.O.W. camp on the night of the escape. Of those seventy-six, fifty are recaptured and executed in cold blood for being a thorn in Hitler’s side. Twenty-three are allowed to go back to the camp; a decision made on political (not ethical) grounds. That leaves a mere three—i.e. 1.2% of the original two-fifty—who make their way to freedom. And so we run smack into another seeming paradox that clings to the film: that people enjoy it as escapist fantasy despite the fact that the men (mostly) do not escape! So how can it be that a story of a failed breakout is somehow uplifting and appropriate for a lazy afternoon during Christmas break? Could it possibly have something to do with the prominence of righteous virtues such as humility, grace, and generosity?

I think that’s a sufficient explanation. For instance, take the relationship that develops between Hendley (James Garner) the Scrounger and Blythe (Donald Pleasance) the Forger. Initially, Hendley is put off by his bunkmate’s effeminate manners. Specifically, how he fusses over making tea and complains that drinking it without milk is uncivilized, and his preference for bird watching over hunting. Charitably, Hendly purloins a can of milk from the guards’ stores and gives it to Blythe and then makes a deal with friendly watchman (Robert Graf) to get Blythe a very specific type of camera. These generous acts begin a friendship that grows quite strong, and when the prisoners are all set for the escape and Blythe confesses he has gone blind from progressive myopia, Hendley severely lessens his own chances of survival by committing to stick with his sightless friend during the breakout. Also consider the hardworking Danny (Charles Bronson), who diligently carves out hundreds of yards of tunnel only to grow claustrophobic and fearful when he finds himself buried by one too many cave-ins. Without the encouragement of fellow Tunnel King Willie (John Leyton), Danny would have risked climbing the fence just to avoid going back underground. (Paul Brickhill, the author of the firsthand account of the escape, had grown claustrophobic from digging and was commanded to remain in the camp so as to not jeopardize the mission.)

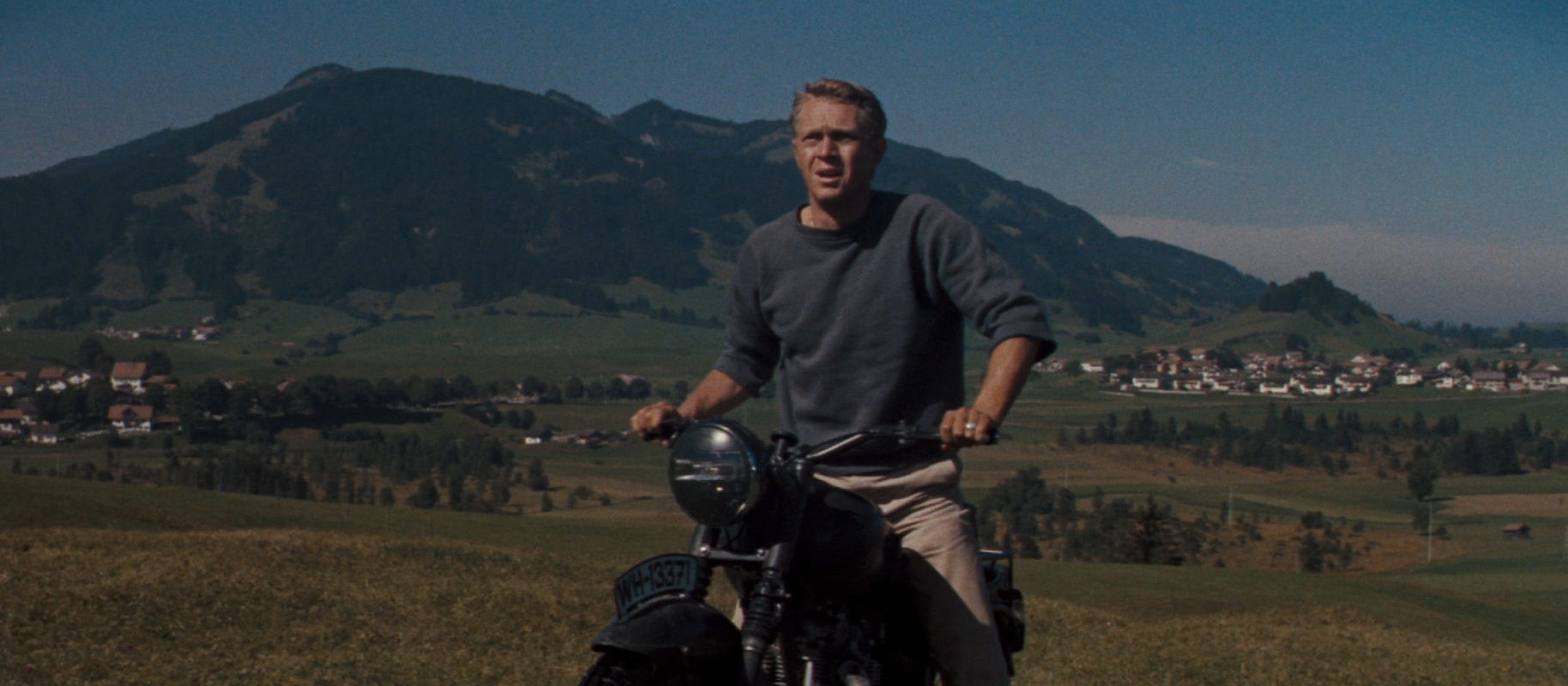

Most important for the operation is the bond between Hilts (Steve McQueen) the Cooler King and Ives (Angus Lennie) the Mole. The two are constantly put in solitary confinement in adjacent cells, leaving them plenty of time for conversation. When the guards discover the primary tunnel during the prisoners’ Fourth of July celebration (led by the only three Americans in the camp), the discouraged Ives makes a break for the fence in broad daylight and gets cut down by a burst of machine gun fire. Up to this point, Hilts has been a rogue actor who planned to break out on his own. Early in the film he had tested a blindspot along the camp perimeter by tossing his baseball toward the fence and walking after it. Later, he and Ives tried to burrow under the fence at this location but were caught and sent back to the cooler. Now, in the dead of night, Hilts scurries to the spot, rips through the fence with bolt cutters, and takes off into the woods. But the death of Ives has stirred something within him and he chooses not to get away. Instead, he does some rudimentary reconnaissance and then allows himself to be captured so that he can bring crucial info back to the prisoners.

All of these men are under the command of Squadron Leader Bartlett (Richard Attenborough) and Group Captain Ramsey (James Donald). The latter is informed by Commandant von Luger (Hans Messemer) that Stalag Luft III is a maximum security camp complete with rocky soil, barbed-wire fences, and watchtowers with mounted machine guns. It was designed to keep all of the “rotten eggs in one basket.” But taking such an approach puts the most creative escape artists together and gives them the opportunity to collaborate. In addition to those I’ve already mentioned, there’s Sedgwick (James Coburn), Ashley-Pitt (David McCallum), MacDonald (Gordon Jackson), Cavendish (Nigel Stock), Goff (Jud Taylor), Sorren (William Russell), Haynes (Lawrence Montaigne), Dai Nimmo (Tom Adams), and Griffith (Robert Desmond), among a slew of other unnamed characters.

While I think that these notions of brotherhood and hope and charity are attractive enough, I would also argue that The Great Escape is indeed escapist in nature. It is increasingly clear as the film goes on that Sturges is working atop a make-believe, Hollywoodized platform. To wit, there’s no talk of Nazi crimes or the Holocaust. The only substantial nod toward the larger conflict involves Sedgwick’s encounter with two members of the French Resistance. Everyone is healthy and robust and the skies are always sunny. Instead of making the horrors of war its subject, it is focused on the camaraderie between the colorfully sketched characters and the minutiae of their escape plan—pilfering wood to fortify the tunnels, hiding the dirt that they dig out, creating civilian outfits, forging travel documents, collecting food. To this end, its true account source is compressed, its characters lumped into composites (several of them transformed into Americans), and a few far-fetched action sequences tacked on for good measure. But even as these creative liberties move The Great Escape away from a gritty realism and toward the realm of pure entertainment, it is lent an air of respectability by its rugged cast, many of whom served in the military. McQueen, Garner, Attenborough, Donald, Bronson, Pleasance, Coburn, Messemer, McCallum, Lennie, Stock, Graf, and Russell all served in the armed forces in some capacity prior to their acting careers. How often can that be said of a war movie today?

The Great Escape is an engrossing escape movie brimming with interesting characters and a bountiful collection of iconic scenes. From McQueen’s iconic motorcycles stunts, to Bronson’s last minute hesitations, to Pleasance faking sight, to the Americans’ Independence Day celebration, to the guards’ discovery of the primary tunnel, to Coburn’s brush with the Resistance, to Jackson’s failure to keep up his disguise—it all adds up to a compulsively watchable three hours.