“Put another quarter in and try again.”

In 1973, Martin Scorsese teamed up with Robert De Niro for the first time and created Mean Streets, a critical success and the first in a long line of sublime gangster flicks from Scorsese. Three years later he would strike gold again with the psychological thriller Taxi Driver. Retrospectively overlooked and tucked between these two films is Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, a film that deserves way more attention than it gets when looking back over the director’s oeuvre. I don’t know why Scorsese decided to follow up Mean Streets with a comedy about a recently single mother road tripping to Monterey with her “spooky kid,” but I’m happy to say that, despite the jarring difference in tone and subject matter from the films that came before and after it, it stands on its own as a great road comedy and character study. It may not have been a trend setter like some of the master filmmaker’s other successes, but it is a very good film nonetheless.

Ellen Burstyn stars as Alice, a housewife who becomes widowed in the opening minutes of the film, then spends the rest of it processing her complex emotional response to her husband’s death. After the funeral and a tearful farewell embrace with her friend Bea (Lelia Goldini), Alice packs up her belongings and her precocious twelve year old Tommy (Alfred Lutter), and hits the road, heading for her childhood hometown where she intends to pursue her longtime dream of being a singer. At times the film paints a brutally realistic picture of the dire straits people find themselves in with their emotions, finances, and relationships. Although it’s often handled with humor, there are several scenes when Alice must confess to Tommy that she has barely broken even while working herself to the bone. Other times, the film skews into exaggerated comedy—that had an audience of two howling frequently—without ever fumbling the dramatic tension.

The broad strokes of the story outline are mostly peripheral, while the real heart and soul of the film are in the interactions between the characters and the very loose action scenes. Many times, the camera runs for a long, unbroken sequence with lots of movement. These shots are never very complex, but still reveal a lot of forethought and directorial smarts, even when the final shot comes off as nearly improvised. A lot of credit is due to editor Marcia Lucas1 (and whoever else was involved in putting the pieces together; so probably Scorsese, who spends a lot of time in the editing room) because many of these scenes are little snippets that cut in and out of a moment, picking up in the middle of a conversation and leaving before it’s over. One of the funniest of these involves Alice’s new love interest, David (Kris Kristofferson), who has invited her and Tommy to his farm. David is talking Tommy through how to milk a cow, and below is the entirety of the scene (leaving out an inappropriate word).

David: “Tommy, don’t use your fingernails. She’ll kick that bucket over.”

Tommy: “Okay.”

(Tommy points the utter at Alice and squirts milk all over her.)

Alice: “Oh, very funny. That’s wonderful darling. How’d you like the holy hell kicked out of ya?”

(The cow gives a small bellow.)

David: “Tommy, watch the fingernails.”

Tommy: “Well she’s got tits the size of cucumbers. What’d you expect?”

Alice: “I just don’t know where he gets that language. I really don’t.”

Tommy: “Think real hard. It’ll come to ya, lady.”

Alice: “Maybe he picks it up at school.”

Burstyn carries the film, and deserves much of the credit for its emotional and dramatic power (she won the Academy Award for Best Actress), but nearly every single other actor brings a great deal to the table and gives a memorable performance in their roles. Lutter, who unfortunately gave up acting, had a truly great sense of comedic timing. He could switch from being annoying to being mature in the blink of an eye. For a moment he even appears sinister when he is gifted a cowboy outfit and walks around like a coin-operated sheriff, slowly approaching the cuddling Alice and David before pulling his revolver and shouting “BANG!” in his mother’s face.

Lutter is joined in the child actor department by none other than an 11 year old Jodie Foster. She is all sorts of rambunctious as a guitar-strumming, Ripple-chugging misfit. She creates a diversion so Tommy can steal guitar strings and later convinces him to drink Ripple (carbonated wine). When he drinks too much and ends up at the hospital, she introduces herself to Alice and says, “It was just a big mistake.” “Whose?” Alice asks. “The store’s.” Audrey’s mother drags her to the door, where she (Audrey) turns and salutes Alice and the hospital staff. “So long, suckers!” she says. She would play a more prominent role in Scorsese’s next film, Taxi Driver.

Before Alice meets David, she has a brief affair with a young man played by Harvey Keitel, who makes the most of about three minutes of screen time. His performance is capped off by a manic episode where his character drags his wife—who had come to confront Alice about the affair—out of Alice’s apartment, then turns around, hand bloodied from breaking through the front window to unlock the door, and ensures that Alice is still planning on hooking up with him that evening. She nods, eyes wide, then begins packing her and Tommy’s belongings as soon as he is gone.

Dianne Ladd and Vic Tayback—who both went on to become regulars in the Alice television series—have a brilliant dynamic as the waitress and short-order cook at the restaurant where Alice finally finds gainful employment. They shout nasty things at one another in order to communicate things that regular people say in plain language, some of it disgusting, some of it funny, some of it both. After she embarasses Alice in front of the entire restaurant, Flo’s (Ladd) transition from contemptible coworker to affable confidant kind of sneaks up on you, and is an adroit bit of storytelling. Valerie Curtin is memorable as the off-beat and perpetually confused waitress Vera, who reads a book called “The Bride Screamed Murder” while serving food, mixes up most of all her orders, and rides home on a motorcycle with her “Daddy Duke” every night.

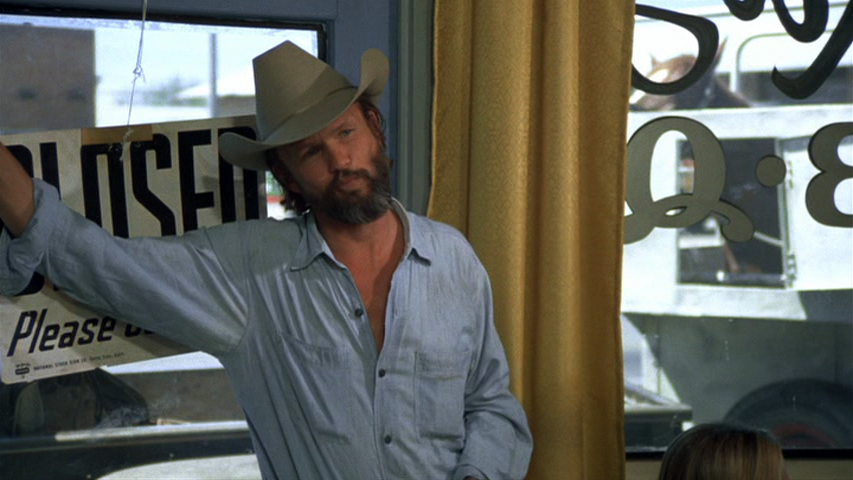

While all the minor roles are great in their own right, the only one that comes close to matching Ellen Burstyn’s performance is Kris Kristofferson (to be fair, he’s the only one given enough screen time to do so). From his first introduction—Alice takes his order and he says, “First, I’d like a big smile.”—to his disciplining of Tommy and trying to teach him guitar like he is his own son, to his frank discussions of his ex-wife leaving him, the old country boy is completely natural. As a bonus, we even get to hear the gravel-voiced singer-songwriter say the words, “wilder’n’a guinea” (wilder than a guinea) when describing how cows act when they smell apples. That last bit illustrates what I love about Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. You could probably sit down with a pen and paper and write out the complete plot in like a page and a half. But so much character is packed into the trivial conversations that litter the film (Tommy telling and re-telling the same unfunny joke; Alice walking through her childhood theater act for David; David explaining how young turkeys will drown themselves drinking rain as it falls from the sky) that these personalities feel real, like they’ve lived real lives outside of the film rather than being conjured up for a two-hour existence.

The only real fault I can find with Alice is that it doesn’t quite land its happily-ever-after ending, which feels more than a bit forced and casts a vague shadow over the rest of the film. But that’s a small gripe and one that likely grates against my sensibilities more than it will those of the average viewer. Most of the other individual scenes are well-written, constructed, and acted. They are strung together into a story that is greater than the sum of its parts, glued into a whole by the superb soundtrack featuring Mott the Hoople, Leon Russell, Elton John, T. Rex, and Dolly Parton. Throughout his career, Scorsese has regularly alternated between the surefire, blood-and-guts-and-Catholic-guilt films that his popular perception is based upon, and more personal projects that range from surrealist comedy to documentary.2 He would become a master of the feature length character study, but this is his first great one.

1. Marcia was the first wife of George Lucas, and also edited American Graffiti, Star Wars, and Return of the Jedi.

2. The director’s range is really remarkable. He’s directed the string of gangster classics, sure, but he’s also directed a black comedy (After Hours) a Bob Dylan documentary (No Direction Home), and a historical drama about Jesuit priests (Silence), among many others.