“Life is a messy weapon.”

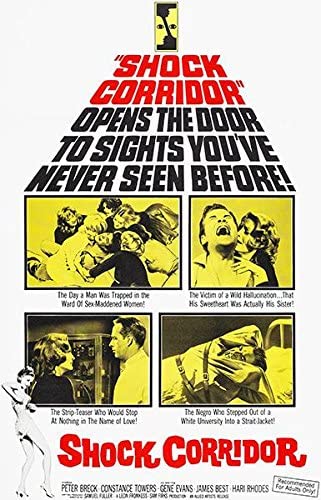

Sam Fuller’s Shock Corridor is a lurid low-budget thriller that uses the convoluted and sordid history of the United States as a backdrop for a descent into madness. A narrative and thematic inspiration for films such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Shutter Island, Shock Corridor is unique in its style, combining creative elements with pulpy tropes and over-the-top acting to form a unique and memorable viewing experience. Its nightmarish exploration of societal issues occasionally borders on the uncomfortable, and it probably would not be green lit by any major studio today. It’s not subtle as it intentionally grates on as many nerves as possible. A quote from ancient Greek playwright Euripides opens and closes the film: “Whom God wishes to destroy, he first makes mad.”

Drawing on Fuller’s early career occupations as a crime reporter and an author of pulp novels, the film is like an outrageous tabloid newspaper. Go-getter journalist Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck) has his eyes on a Pulitzer, and will stop at nothing to get it, going so far as to practice a routine with a psychiatrist that will allow him to bluff his way into a mental hospital so that he can solve an open murder case. His girlfriend (Constance Towers), who makes ends meet by moonlighting as an exotic dancer, poses as his sister, filing a formal complaint stating that he tried to force her to commit incest. After putting on a believable performance, answering the doctor’s probing questions as they are asked according to plan, and exploding in rage at the correct moment, Johnny is restrained and taken to the asylum. Once there, he encounters three characters—all witnesses of the crime—who represent disturbing societal ills that irk the writer-director.

First is the disgraced Korean war veteran named Stuart (James Best) who was brainwashed by Communists. He eventually returned to the United States in a prisoner exchange and was publicly reviled as a traitor. The film portrays him not as an enemy but as a sympathetic figure, who relapses back to reality, questioning why he ever left the family farm and joined the army in the first place. Even though the long scene in which Stuart breaks down is emotional (emphasized by a long take), most of his screen time is used for comedy; he is in the mental hospital because he imagines himself to be the Confederate General James “Jeb” Stuart. He endlessly pores over maps of the Gettysburg battlefield and only responds to Barrett when he pretends to be fellow General Nathan Bedford Forrest, an accomplished Civil War General who later became a prominent leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

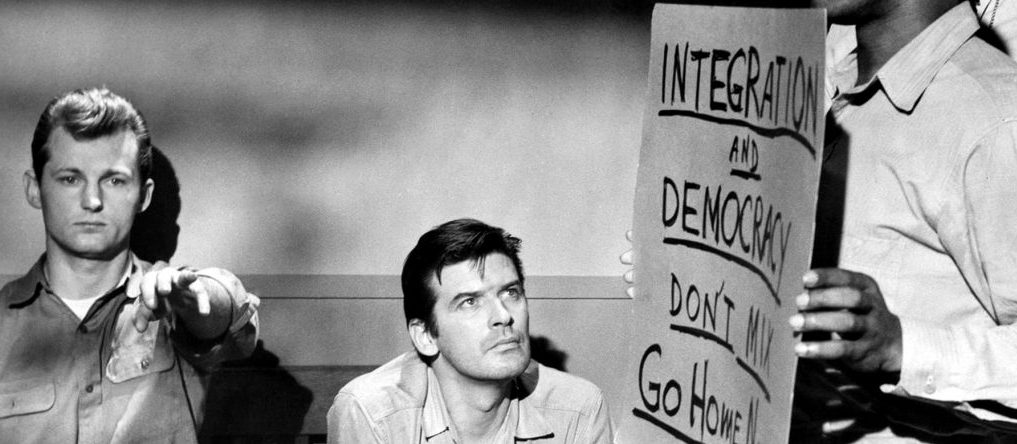

Barrett’s impersonation gives him an in with Trent (Hari Rhodes), one of the first black students to attend a non-segregated university. The mental and emotional stress of being a martyr for social progress caused him to break and he now spouts off white nationalist dogma and steals pillowcases to make Klan hoods. (I wonder if Dave Chappelle’s skit about the black white supremacist took inspiration from this character.) As Trent sits alone with Barrett, he pulls one of the pillowcases from beneath his shirt and points to a symbol. “It’s a sign of the invisible empire,” he says. “If Christ walked the streets of my hometown he’d be horrified. You’ve never seen so many black people cluttering up our schools and busses and cafes and washrooms! I’m for pure Americanism! White supremacy!” But Fuller didn’t write those words; they were actually pulled from congressional records and were spoken by an American Congressman.

Last is Boden (Gene Evans), a renowned physicist who worked on the hydrogen and atom bombs, who retreated from the knowledge of the destructive power of intercontinental ballistic missiles by reverting to the mentality of a six year old and scribbling portraits of his fellow inmates. What we are left with then is a film less about the central plot concerning the journalistic hubris of Johnny Barrett than it is about an entire population being gradually affected by xenophobia, racism, and paranoia surrounding the Cold War. In that respect, it deserves mention next to films like The Manchurian Candidate and Dr. Strangelove, though it is not quite as good as either of those.

The social commentary is hard to miss, but it is difficult to grasp exactly what Fuller was trying to say other than that these issues deserve some attention. It’s clear that he had some thoughts on some things, but they come out all jumbled and mixed with pulp, sex, and schlock. There’s an extended scene of Constance Towers doing a striptease, and another in which Barrett accidentally wanders into the “nympho ward” and is attacked by half a dozen sex-crazed women. Fuller was always pushing the envelope, though, following up Shock Corridor with Naked Kiss and returning to the theme of racism with White Dog two decades later.

Though the writing sometimes lets down the performances, the actors are mostly excellent. Barrett in particular is very good in the scenes where physical altercation is required, while Towers has several scenes in which close-ups frame her emotionally distraught face. James Best and Hari Rhodes are both committed to their roles, and do an excellent job of shifting their characterization when they have their lucid moments. One character I haven’t mentioned yet is Pagliacci, played by the enormous Larry Tucker. He is endlessly entertaining and provides several moments of much-needed comedy throughout the film (my favorite of which is when he sings opera when a fistfight breaks out in front of him).

Several times, the black-and-white aesthetic is interrupted by dreamscapes of half-remembered, half-fantasized memories, narrated by the recently lucid inmates. The footage used was from several other Fuller projects, and was an unexpected and pleasant break from the heavy themes present throughout. Originally, Fuller conceived of Shock Corridor as an idea for a Fritz Lang film, and I would have been very interested to see what kind of nightmarish film we would have gotten from the man who made Metropolis (1927), M (1931) and Ministry of Fear (1944).

Unfortunately, the film doesn’t really come together as a whole. The cheap theatrics and threadbare depiction of Barrett’s own descent into insanity (which is what the surface level plot is “about”) do a disservice to the jumbled yet intense message of the film. The pulp elements are welcome, but there’s too much yelling and Barrett has a constant voiceover of his own thoughts that would probably work better if only about a quarter of them were present. The nympho ward scene and the extended striptease simply feel out of place.

It’s shocking and schlocky. Though it fumbles some of its main plot and the message of the film is somewhat convoluted and drowned out by the intensity with which it is portrayed, Shock Corridor is an engaging and watchable film from an auteur unafraid of controversial themes and pulpy writing. It’s certainly not for everyone, and may make you squirm a bit, but you’ll be drawn to it despite its flaws.

Sources:

Johnson, Rich. “How Shock Corridor reflected the madness of 1960s America”. Little White Lies. 2 September 2019.