“There’s not much I can tell you about this war. It’s like all wars, I guess. The undertakers are winning. And the politicians who talk about the glory of it. And the old men who talk about the need of it. And the soldiers, well, they just wanna go home.”

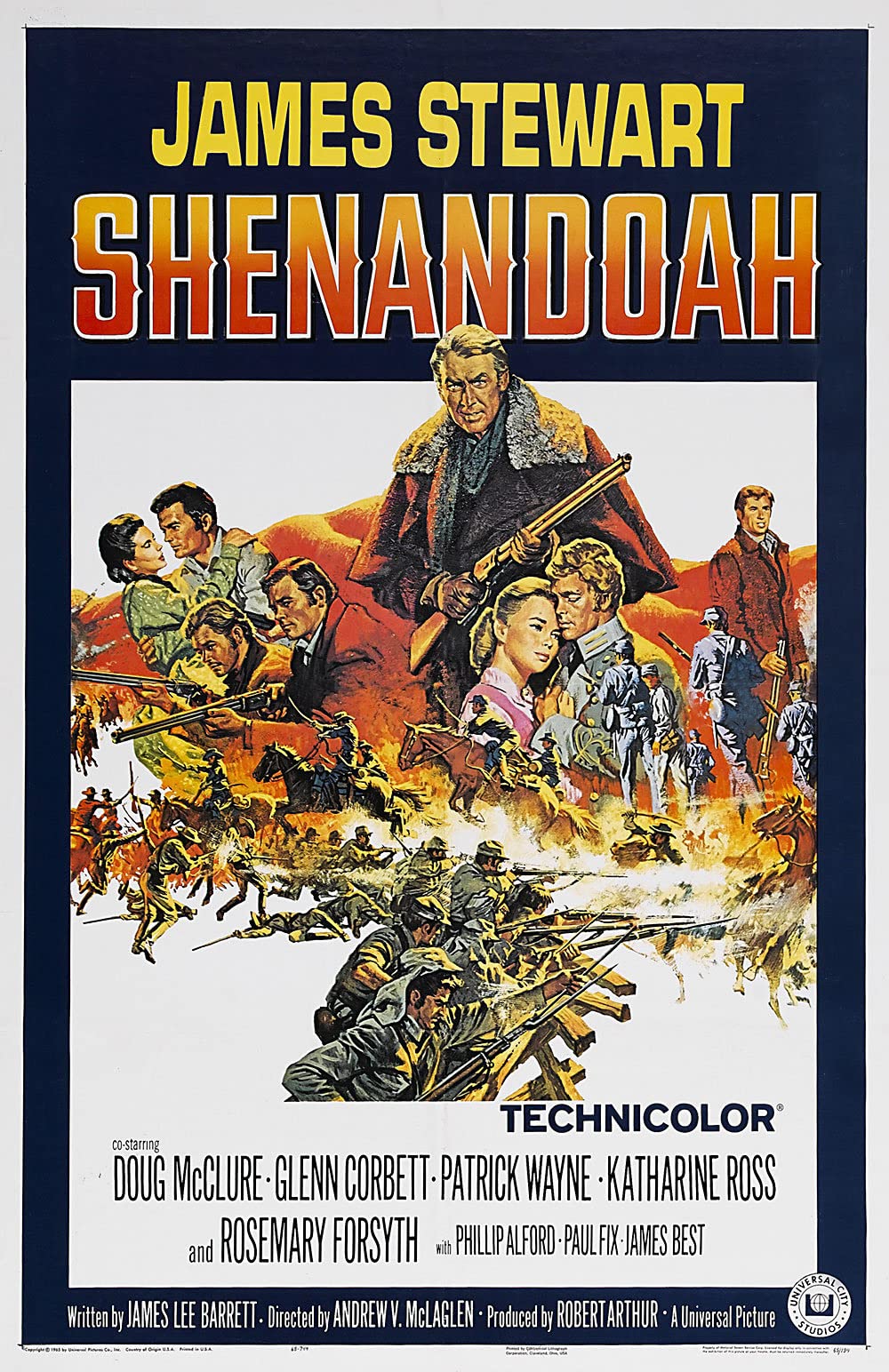

“We cleared five hundred acres without the sweat of one slave,” a cantankerous old cigar-chomping James Stewart says when a Confederate officer comes to his farm and tries to conscript his boys to fight in the Civil War. In Andrew V. McLaglen’s wartime drama, Shenandoah, Stewart plays a widowed Virginia farmer named Charlie Anderson: a hard-nosed patriarch who’s single-handedly raised his six sons and one daughter for almost two decades, who’s mastered the give-and-take with the fertile land, who’s self-made and doesn’t let anyone, not even God, forget it. He tries to take the same tact as regards the war, but when the armed conflict encroaches on his farm and his family, circumstances dictate that he must quit ignoring it and take action. With Stewart leading a first rate cast of supporting players, Shenandoah is by turns violent and heartwarming—a reassuring picture that isn’t afraid to dip its toes into darker waters, and by doing so handily earns its emotionally stirring conclusion.

Charlie Anderson has raised his seven children to be hard-working, kind, resourceful, loyal, and as per the dying wish of their late mother, God-fearing. All but one of them are of marrying age, but all still live at home with their father. Jacob (Glenn Corbett), John (James McMullan), James (Patrick Wayne), Nathan (Charles Robinson), Henry (Tim McIntire), and Boy (Phillip Alford) help Charlie run the farm, while Jenny (Rosemary Forsyth) and James’ wife Ann (Katharine Ross) tend to the housework. Despite the hardships that come with raising a large family by oneself, Charlie is basically content with his lot in life: surrounded by his loving offspring, beholden to no man, the proud owner of a large swath of fertile farmland that provides for his family.

But the times they are a-changin’. Isolationist by nature, Charlie tries to ignore the Civil War skirmishes that are raging within earshot of his farm. He’s not a pacifist, per se, but he believes it’s not his battle to fight and he should not be compelled to offer his sons, horses, or supplies to fight for causes that do not concern him. In his mind, the Union has no quarrel with him as he has never owned a slave; and the Confederacy does not have a right to his resources simply because he lives in Virginia. Even as troops are gunned down on his land and several of his sons express interest in enlisting, he remains resolute, allowing his daughter to be married to a Confederate soldier and welcoming his first grandchild into the world. But his stubbornness cannot stop the relentless encroachment of the war, and when his youngest son, Boy, is snatched up by Union forces who mistake him for a Confederate soldier (Doug McClure) and cart him away as a prisoner of war, Charlie must face reality. Disregarding the reasons for the larger conflict, it has now become personal and thus concerns him a great deal. He’s involved whether he wants to be or not.

Charlie: Where do you think you’re going?

Jenny: Wherever you go, Papa.

Charlie: Yeah, from what these preachers tell me, where I’m going you wouldn’t like it there at all.

Jenny: You may be on your way but you aren’t there yet, Papa.

Charlie: Just nevermind that. You’re not going with us. Unstrap, unhook, get out of your brother’s clothes. You’re a woman!

Jenny: Yes, I’m a woman but I don’t see anybody here that I can’t outrun, outride, and outshoot.

On the whole, Shenandoah is quite sentimental. It generates a folksy charm with its Technicolor presentation, frequent integration of matte paintings, and comedic backyard brawls. The dialogue includes numerous occasions of misty-eyed rumination on life and love and legacy. On occasion, it almost steps too far into coincidental melodramatics, specifically when Boy’s life is spared by his black childhood friend (Eugene Jackson) who has run off to join the Union forces; or when the Andersons fail to find Boy when they hold up a train but reconnect with Sam (McClure) as a consolation prize. However, even as all of those elements lay the groundwork for a cloying, life-affirming type of conclusion, McLaglen weaves in a sinister streak that provides a satisfactory balance. To wit, the story doesn’t necessarily call for any of the Anderson children to die; Boy’s capture is sufficient narrative justification for the mechanics of the story. But to really hone in on the thematic territory—in this case, the importance of family—James Lee Barrett’s screenplay calls for the deaths of three of them. Similarly, even as McLaglen works in several comedic fight scenes, there are others that starkly portray death. There are several nicely staged military confrontations with some serious stunt work, guerilla warfare in which Confederate forces hide out in trees for an ambush and blow up a covered wagon, and even some immersive footage borrowed from Raintree County.

Shenandoah is almost certainly historically inaccurate in some of its details. (I wouldn’t know, I’ve been putting off Bruce Catton’s Centennial History of the Civil War for like five years.) It’s interesting to contemplate the film’s message: to discuss whether or not it takes a side in the conflict or if it is staunchly anti-war; to consider how contemporarily the writers were thinking as they wrote just as the Vietnam war was heating up; to acknowledge the film’s proximity to the passage of the Civil Rights Act. But I found these messages, if they are indeed messages and not simply trappings, to be secondary to themes of family solidarity and common-sense morality. And of course all of those things are necessary to engage the viewer, but most of them take a backseat to the winsome cast which operates in smooth unison. I’ve already mentioned many of the core cast members—and Stewart prominently towers above his supporting cast members with an authoritative, even-tempered performance overflowing with his practiced mannerisms—but I would be remiss to skip over Denver Pyle’s country preacher, Paul Fix’s family doctor, Strother Martin’s train conductor, James Best’s rebel soldier, or George Kennedy’s world-weary Union colonel, all of which are richly drawn and establish senses of scale and community.