“He tells me that disease is the love of two alien kinds of creatures for each other.”

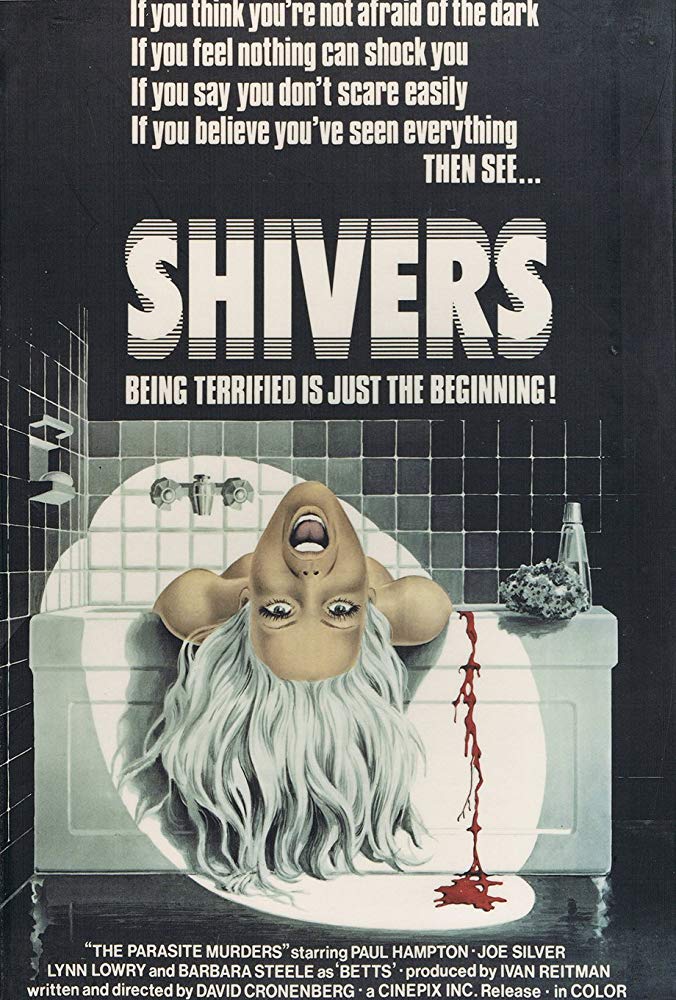

David Cronenberg’s provocative feature debut, variably known as Shivers, They Came From Within, and The Parasite Murders, has proven divisive since its release. It’s now perhaps simplest to pigeonhole the low-budget gross-out as a rough draft harbinger of the auteur’s subsequent shockers—films like Videodrome and The Fly. In the ensuing decades the man has carved out and dominated the body horror niche and his work, while rarely categorized as mainstream, has been enthusiastically received, analyzed, and canonized in certain cineaste circles. Here we can see his preoccupations with psychosexual disorder, disease, mutilation, the relationship between mind and body and technology, the distinction between man and animal—themes he would explore throughout his career. But if we mentally transport ourselves back to 1975—my parents were in grade school, the AIDS epidemic was yet to occur, gore and sex were just entering mainstream filmmaking by way of New Hollywood—it becomes obvious that this early work would not land well with general audiences. It was so repellent to his fellow Canadians that Cronenberg’s landlord kicked him out of his apartment by invoking a “morality clause” in the lease and one critic stated “[…] perhaps Canada should not have a film industry.”

With two experimental shorts under his belt, Cronenberg penned and marketed what he hoped would become his feature debut—he called it Orgy of the Blood Parasites. Scouring the web has failed to turn up an answer as to why the Canadian Film Development Corporation (which provides public funding for Canadian productions) greenlit the script but forced a name change. It was obviously meant to stir up the prudes, but in my estimation, the original title fits the contents and tone of the film perfectly with all its onscreen violations of taboos, black humor, and subversion of genre conventions.

Shivers begins with creative modesty. Shutter-clicking through a slideshow of a luxury high rise apartment building outside of Montreal, a narrator describes the getaway in all its neon and polyurethane glory. It’s a self-contained paradise complete with a swimming pool, golf course, pharmacy, dentist office, dry cleaner, delicatessen, etc. You’ll never have to leave. But Cronenberg wastes little time before shoving our faces in grimy smut, intercutting the smarmy advertisement with a diabolical scene. Seemingly possessed, a rogue doctor strangles a nubile schoolgirl, tapes her mouth, slices open her exposed belly, dowses her exposed innards with acid, and then takes the scalpel to his own throat. We will learn that this act stemmed from a bizarre research experiment with the stated aim of unlocking humanity’s primal sexual nature. A lab-grown parasite has been unleashed that enters (and exits) the body through any available orifice, quietly grows within the stomach, and transforms its host into a sex-crazed maniac. The fulfillment of the host’s irrepressible desire propagates the parasite, and soon a rabble of degenerate sex fiends are prowling about the hotel.

The story jumps around and briefly visits an array of neurotic guests at the Starliner as they succumb to the parasitic frenzy one by one. Roger St. Luc (Paul Hampton), the hotel’s resident physician, is the ostensible protagonist but he isn’t really on screen enough to fulfill that role. Neither is Nick (Alan Migicovsky), though his prolonged encounter with the squirmy slugs will etch his visage into your memory. In his first attempt to rid himself of the parasite, he vomits a regurgitated blob from his balcony, the bloody mass ricocheting off an elderly woman’s transparent umbrella several stories below. Later, laying in his bed, he gently speaks to the slugs as they bulge up from his stomach via the creative use of air bladders. Instead of a main character, Cronenberg utilizes a half-baked ensemble of doctors, scientists, nurses, elderly vacationers, young couples, businessmen, and resort employees amongst which the parasites transfer. They dodge in and out of mouths, latch onto faces (there’s one scene here that’s recreated nearly verbatim in Alien), and even crawl through ventilation ducts and drain pipes on their own.

With only a small budget to work with, cheap practical effects were utilized to provide shock value. Like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Night of the Living Dead, the unpolished, bloody, raw effects work of Shivers makes its graphic depictions of gore feel realistic and organic. Coupled with the lo-fi technical quality, this lack of elaborate effects achieves a disturbing realism.

Critics have analyzed it through the lenses of class and Freudian psychology, among other things. For instance, consider how these wealthy guests have walled themselves off from the hoi polloi; or how several of them are covertly cheating on their spouses before the slugs pervade, their adulterous romances liberated by the parasite. Those metaphors fit but are secondary to the central theme of the perils and potential pleasures of mixing biology and technological innovation starkly illustrated by a transgressive intermingling of horror and eroticism. Disorienting and difficult to stomach, it’s a suitable introduction to that vaguely queasy feeling that Cronenberg honed in on in later works.