“You don’t get it. It’s so easy. All you gotta do is… look up. Nothing else matters. Don’t you see?”

Alex Proyas began his career as a music video director, then directed some short films before pond-hopping his way into the hearts of goth and sci-fi fans with the one-two punch of The Crow and Dark City. Both of those films have loyal cult followings, but his debut, Spirits of the Air, Gremlins of the Clouds, shows earlier evidence of his visionary aesthetics and esoteric sensibilities. Boasting dazzling cinematography and set design (especially for its budget) the film features only three cast members alone in the Australian desert.

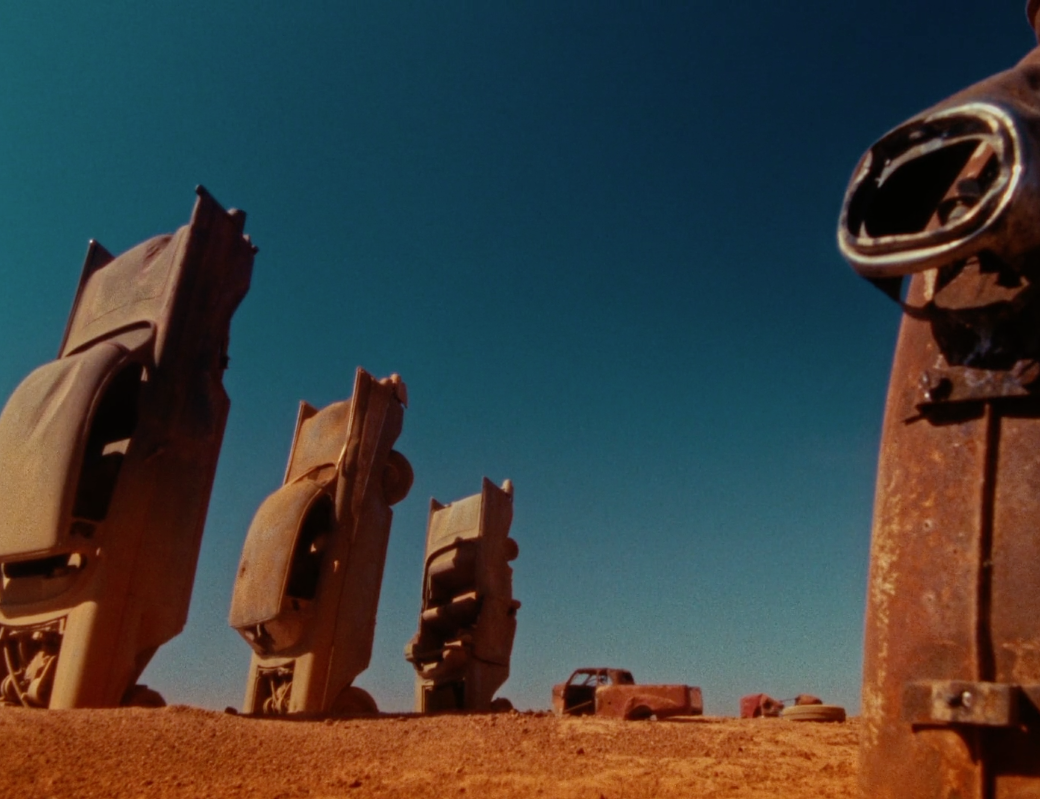

The visuals are stunning as Smith (Norman Boyd) walks alone through the desert, eventually stumbling his way to the isolated dwelling of Felix (Michael Lake) and Betty (Rhys Davis) Crabtree. There are gobs of religious-themed art and goofy-looking gadgetry to jazz up the set and keep things visually interesting—cars half-buried vertically into the ground, tattered flags, ramshackle outbuildings, and crucifixes everywhere. The colorful landscape and stylized wardrobe are reminiscent of fellow Australian filmmaker George Miller’s Mad Max and its sequels mixed with the zaniness of Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits or Brazil, while the shot compositions take inspiration from Tarkovsky (Solaris, Stalker).

We aren’t given much of a backstory, but in this future state of the world, technological progress has screeched to a halt, and humans find their purpose in individual endeavors, apparently going half-mad by virtue of a lack of outside ideas. When Smith first arrives, Betty believes him to be a demon, using a crucifix to ward him off and murmuring to herself in fear throughout the trio’s first shared meal. When Smith tells Felix that he plans to head north, Felix warns him of the impassable cliffs in that direction. Felix—obsessed with building a glider—has already permanently maimed himself and rolls around the premises in a wheelchair with colorful spirals adorning its spokes; but he is able to convince Smith that the glider is his best chance for outrunning the unseen pursuers that he is fleeing.

The characters are very eccentric and intentionally overacted. Betty, especially, is outrageous in her high-strung paranoia and religious fanaticism. She wears face paint (Proyas apparently liked painting his leads’ faces early in his career), plays an oversized homemade cello, and wears several different outrageous hairstyles throughout the film as she screams the majority of her dialogue. Felix is obsessed with flying, flapping his arms like wings and overreacting to almost every situation, his facial expressions emphasized like a silent film star. However, the outlandish caricatures remain consistent and don’t feel too out of place; they just give the world a hammed up, slightly campy vibe. This fits well with the simplistic plot of building a hang glider to fly over a distant mountain range, which is itself kind of silly and hard to take seriously.

Unfortunately, for all its technical brilliance and artistic vision, it falls well short in the story department. There simply isn’t much of substance here beyond what I’ve just described, yet it takes a lethargic hour and a half to reach its conclusion. The scenes are full of non-sequiturs that weigh down the first two thirds of the film until a faint bit of bittersweet hope is presented towards the end. Without the wonderful set design, mesmerizing cinematography from David Knaus, and gentle synth compositions of Peter Miller, the film would be a snoozer. But the eccentric acting, along with the stunning visuals, lead me to view this film more as much as an extended piece of theme-driven performance art as a narrative film. Which is not to say it’s completely bad as a narrative film; just that it’s severely lacking. I mean, they shot this thing for half a million bucks; that’s cheap. And they got a lot of stuff right; knocked it out of the park, even. Taking into account the weird blend of technical sophistication and artistic composition with the campy acting and idiosyncratic imagery, it is a thoroughly confounding work. It certainly has little mass appeal, but I think it may deserve the same cult appreciation that his other early films enjoy.

Despite its shortcomings, Spirits of the Air is brimming with promise, some of which was fulfilled with the director’s next two films. However, since the turn of the century, Proyas has released a string of middling films, with only 2004’s I, Robot as a possible exception. His last two films were Knowing—the pseudo-profound crazy-version-Nic Cage disaster film—and a cheesy, white-washed Gods of Egypt. They’re harmless, run-of-the-mill blockbusters, but they lack much of the artistic vision that Proyas displayed early in his career. It is disappointing that a director who was poised to become one of the most distinctive auteurs of the new century has not been able to capitalize on that early career promise. On a minuscule budget for Spirits ($500k Australian) he was able to craft a visually breathtaking film and show off his eye for image composition. The budgets of his last three films have all been more than one hundred times that, and yet the films simply don’t measure up. Somewhere in there is a lesson about creativity and (lack of) resources.

For fans of Proyas, this will be worth going back and checking out. For someone who just likes unique visuals or the post-apocalyptic desert aesthetic, it may be worth querying a search engine for some screencaps. For the average pop-corn movie-watcher, don’t even kid yourself—find something else to watch.