“Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.”

Roman Polanski is often viewed as a jack of all trades, a one-man filmmaking crew unto himself, a director, screenwriter, editor, and actor with a unique artistic vision that encompasses both narrative and visual storytelling. His personal stamp is undeniable across most of his oeuvre, even when he’s “just” directing.

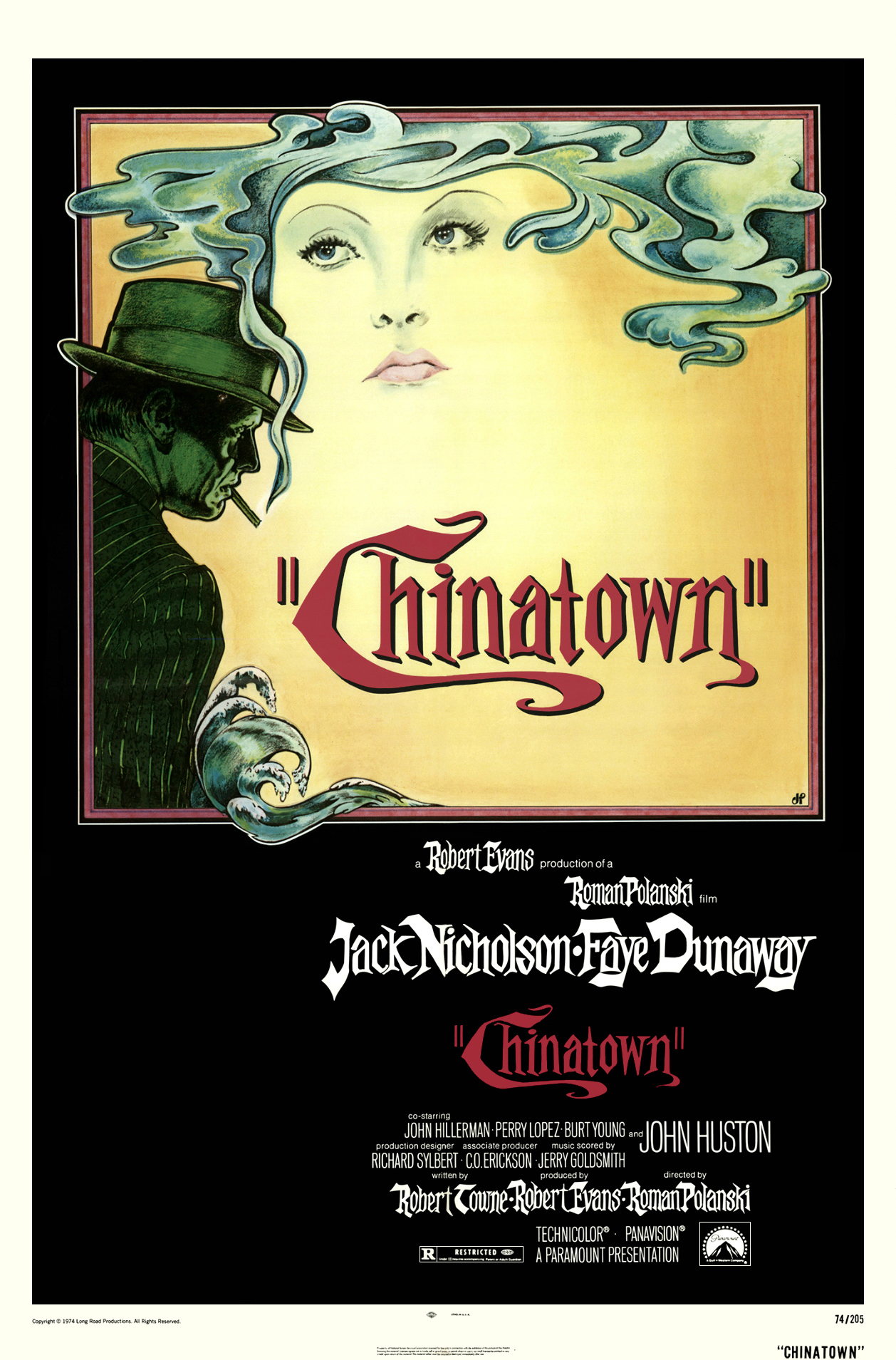

But then there’s Chinatown, one of his towering achievements and yet not his in the same way that Repulsion or Cul-de-sac or Rosemary’s Baby are his. This is because star Jack Nicholson and screenwriter Robert Towne are also auteurs who tend to put their personal stamps on projects. And so Chinatown is, however uneasily, a much more artistically collaborative effort than most of Polanski’s other films.1

Towne’s labyrinthine yet efficient screenplay is rightly considered a masterpiece, a seedy mystery based in real history with an admixture of political resonances, melting pot social conflicts, and religious symbolism, rife with subtle clues that you don’t spot until the second or third viewing, as you stumble along with Nicholson’s blundering gumshoe in pursuit of something like the truth or something like justice while official law enforcement (Perry Lopez, Richard Bakalyan) proves incapable of sniffing out either. What begins as a simple, intriguing mystery gradually exposes the entire wicked ecosystem of 1930s Los Angeles and a familial scandal to rival the revelation of Luke Skywalker’s heritage.

Along with a game Nicholson—who plays his character stoic, cocksure, and witty, a little sleazy but with more heart and moral fortitude than Spade or Marlowe—Polanski expands the neo-noir palette to turn even the desert in broad daylight, a tranquil orange grove, a lush backyard garden, a dried riverbed, or the public hall of records, into environments fraught with menace. Polanski himself has a visible hand in producing this unsettling atmosphere when he shows up as a thug who takes a switchblade to Nicholson’s nose for sticking it where it doesn’t belong.

Nicholson’s bandage has a primal power as a visual reminder of violence. But the sense of pervasive dread, of unidentified malignancy, comes not from what we see and hear but from what we don’t. We glimpse clues whose explanations remain beyond the detective’s grasp: like why does everyone have a cold in the middle of summer? We see signs of political corruption as the city’s water is rationed and the farmers’ crops left to wither while runoff is dumped into the ocean during the dead of night.

The woman (Dianne Ladd) who contracted the sleuth to spy on her husband turns out to be a fraud. The actual wife (Faye Dunaway) is skittish, and soon widowed when her husband, the water department’s chief engineer (Darrell Zwirling), is fished out of an aqueduct. She asserts herself at times, and even cons and seduces Nicholson’s private eye, but she clams up or stammers when confronted with certain topics—especially when asked about her magnate father (John Huston), a wolf in sheep’s clothing whose presence is so urbane and folksy and subtly sinister that when he reappears later after a first encounter with Nicholson, after we’ve learned a thing or two about him, that one can’t help but feel physical revulsion toward a man who directed several masterpieces of his own including the seminal noir The Maltese Falcon.2 As surely as he raped his daughter he is now raping the land. And for what? “How much better can you eat? What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” Nicholson asks the multi-millionaire. “The future,” he replies. “The future.”

Belonging to a class of cynical ‘70s thrillers that includes Klute, The Long Goodbye, 3 Days of the Condor, and Night Moves, and an antecedent of the crime fiction of James Ellroy and the terrific detective game L.A. Noire, Chinatown embraces the pessimism and moral ambiguities of the Nixonland era and integrates them into a cool homage to the film noirs of Hollywood’s golden age without ever toeing the line of parody or pastiche or suggesting a retreat into the nostalgic past is a viable solution. It stands as one of the most stylish, suave, and sophisticated big studio pictures ever made, and concludes with one of the bleakest cinematic gut-punches of all time that leaves even our unflappable P.I. slack-jawed and mystified, a blind-luck shot from a revolver that transgresses the carefully laid mystery to reveal the deeper tragedies of mankind’s fallen condition.

1. This should not be taken as any sort of slight against cinematographer John A. Alonzo (Bloody Mama, Harold and Maude, Scarface) or editor Sam O’Steen (Cool Hand Luke, The Graduate, Rosemary’s Baby), or composer Jerry Goldsmith, or production designer Richard Sylbert, who all do commendable, indispensable work on the film.

2. I try especially hard to separate the art from the artist in cases where I don’t see eye to eye with the artist in question or where I don’t agree with their behaviors, but it is kind of hard to ignore the fact that Polanski is a convicted sex offender when his film is actually about that very subject.