“Do you know what my next assignment is? I’m having lunch tomorrow with an eighty year old ex-con who has just carved an entire replica of the Danbury Penitentiary out of soap.”

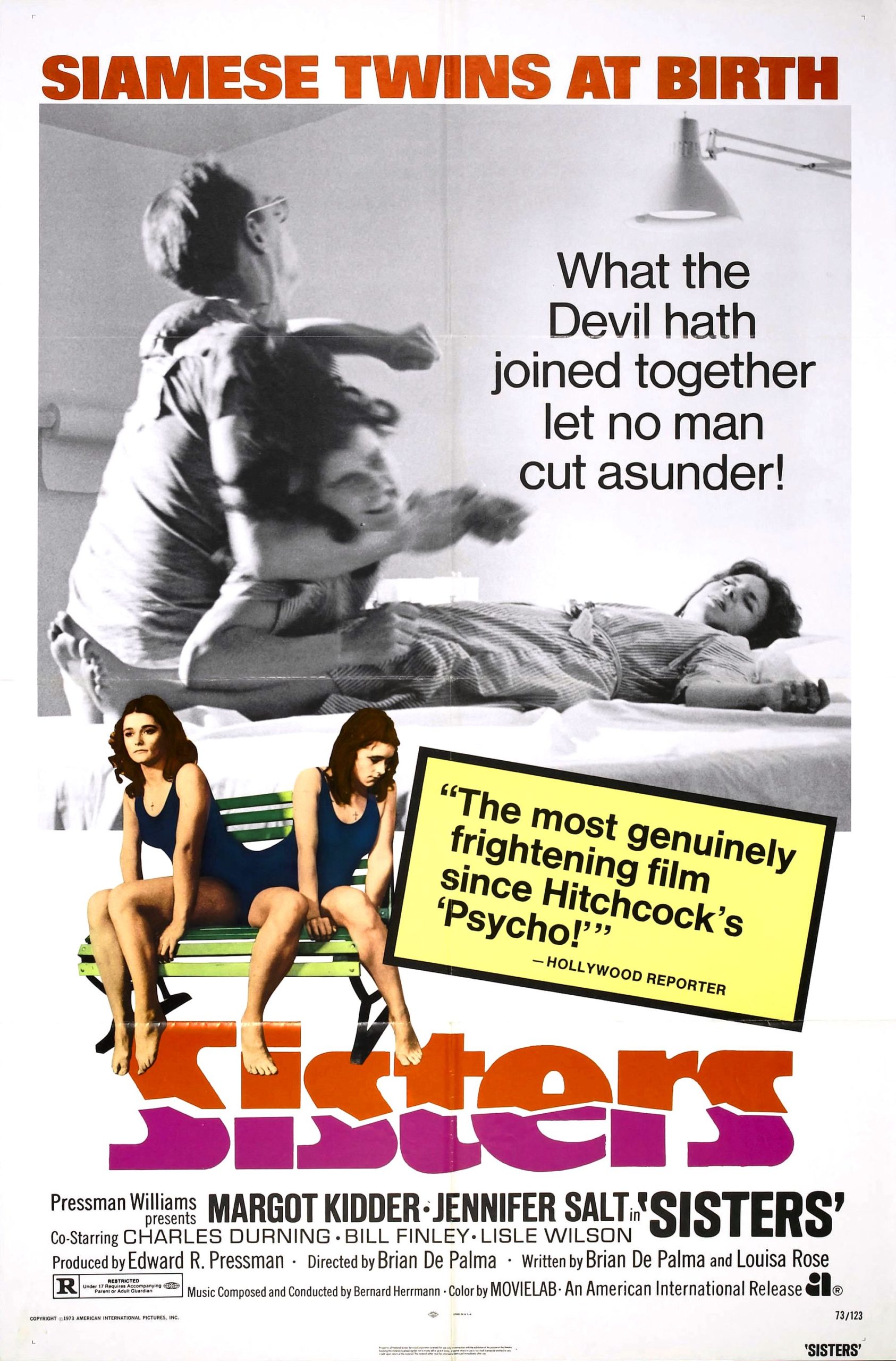

Sisters is one of Brian De Palma’s early career homages to the master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, and the first made in the style that made him popular. It is very entertaining and often exhibits a somewhat unhinged, go-for-broke filmmaking philosophy. Made on a low budget, the film is surprisingly agile in its use of various locations, though many of the creative elements are showcased within a single apartment building.

The film begins with what amounts to a satirical short film, concisely made if woodenly acted. It is pretty well self-contained, and only really expands because there is a witness to the murder, giving us a Hitchcockian role of the disinterested party uniquely privy to information that no one else believes. The first scene is on the set of a game show called “Peeping Tom”—a nod to the voyeuristic tendencies which will lead to the witness of the upcoming murder.

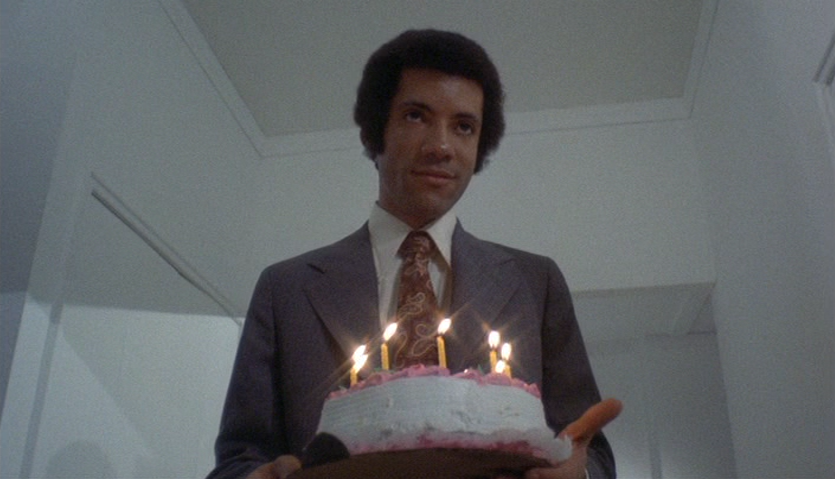

After meeting Danielle (Margot Kidder) on the set of the gameshow and winning dinner for two at a local restaurant, Phillip (Lisle Wilson) invites her to dine with him. Though their date is interrupted by a towering creep named Emil (William Finley) who claims to be Danielle’s ex-husband, Danielle asks Phillip to come home with her. They make love, and the next morning Phillip dresses quietly in the bathroom while he listens to Danielle argue with her sister Dominique, who stopped for a visit to wish her twin sister a happy birthday.

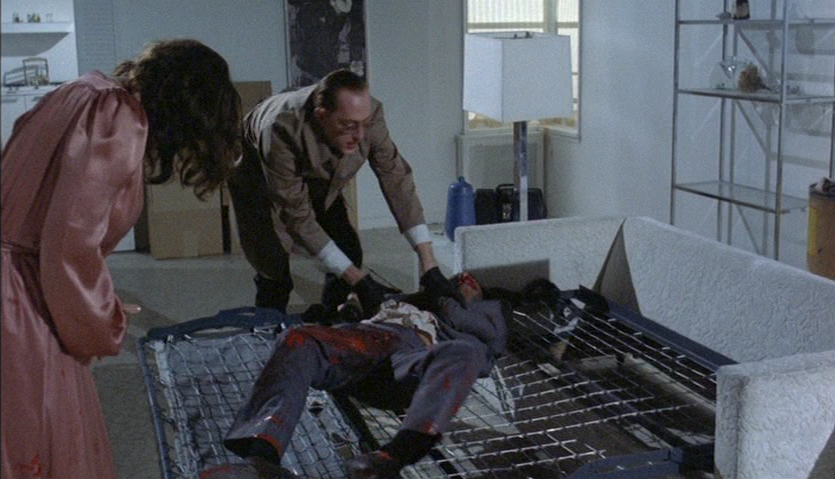

When Phillip runs to the drugstore to pick up some pills for Danielle, he stops and gets a birthday cake for the girls, asking the bakery assistant to spell out “Happy Birthday to Dominique and Danielle” on top of it. When he returns, he finds Danielle, or maybe Dominique, sleeping on the fold-out couch. He presents the surprise, but she grabs the knife and shoves it into his groin, then his mouth, then hacks and stabs him repeatedly. It remains ambiguous which of the two went berserk on Phillip, but in any case, Emil arrives and helps her scrub the apartment of evidence before the police arrive, hiding the body in the retractable couch during the search. In this long scene, there is creative use of split screen, allowing the audience to see multiple perspectives of what is happening—sometimes presenting the same characters from multiple angles, other times following the action occurring in completely separate places.

The main storyline is kicked off when Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt), a spunky newspaper columnist, witnesses the murder from her apartment building, from which she can see Danielle’s (similar to Hitchcock’s Rear Window). Grace is a reporter for the Staten Island Panorama, and has written a recent string of articles critical of the police force. Though they reluctantly follow her lead they are unable to find any evidence of a crime. While they are searching the apartment, Danielle is adamant that she lives alone, and has been alone all morning, and claims that the duplicate sets of clothes are not for a twin, but for her acting gig. Near the end of the search, Grace finds the cake—evidence to her that Danielle does have a twin—but she drops it as she tries to show it to the police chief.

The case is dropped by the police, but Grace refuses to doubt her own eyes and pursues the case herself. Her editor allows her to do so on the condition that she is accompanied by a private detective (Charles Durning). When the private detective searches the apartment, he finds a case file on the Breton sisters—Siamese twins that had recently been surgically separated. When he leaves the apartment building, he is in the guise of a window washer, and unsuspiciously helps a moving company lift the heavy couch onto a moving truck. Believing the body is in the couch, the detective decides to follow it wherever they take it. While he follows the couch, Grace finds a reporter (Barnard Hughes) who had written an article on the Breton sisters. Through their conversation, Grace learns that Emil is Danielle’s doctor, and that Dominique had died on the operating table during the twins’ surgical separation. After the mysterious opening, in which the audience is kept mostly in the dark, the middle portion of the film consists largely of the gathering of information, filling in context for the bizarre finale.

The ending of the film is a strange trip. Grace follows Emil and Danielle to a mental hospital, where she watches Emil sedate Danielle, but before she can phone the police, she is caught. Emil convinces the staff that Grace is a new patient, and has her locked in a room where he hypnotizes her, convincing her that the murder never occurred. Grace experiences weird dreams where she takes the place of Dominique, conjoined to Danielle at the hip, featuring trippy black-and-white aesthetic reminiscent of David Lynch’s Eraserhead (in production at the time but not released until 1977). Unnerving visual effects are accompanied by frequent Hitchcock collaborator Bernard Herrmann’s score. Emil explains to Danielle that whenever he tries to make love to her, “Dominique” will come out and she will become violent—that is why she has been on a steady diet of pills. He tries to confront her about the murder, but she rips into his groin with a scalpel, and he bleeds out lying on top of both Danielle and Grace.

The last twenty minutes of the film really test the audience—who, up until now, could have simply thought the film was a gorier version of a standard Hitchcock film, or an off-beat noir story. William Finley—who appears creepy and overbearing yet loyal in the beginning of the film—is great as the sordid villain and doomed lover. Forcing the audience into feeling sympathy for his character as he dies without being able to physically love his wife makes for a weird climax. Because De Palma had such a low budget and lesser known actors, and most importantly, working within the New Hollywood era, he was able to take some risks here that his inspiration would not have been able to. He heaps on the morbidity and gore, and the strange psychological oddities are pressed to the extreme. Kidder and Salt both fit their roles perfectly, though Salt’s role only calls for her to be mostly one-dimensional through most of the film. Kidder’s complex performance is noteworthy for portraying two characters, which are differentiated mostly by her actions, not make-up or costume.

The entire cast, though, plays their roles tongue-in-cheek, aware that the subject matter will likely mean this film is seen through a lens that at least partially views the film as camp. And though the comparisons to Hitchcock make sense—there is clear inspiration from Rear Window, Rope, and Psycho—the homage is really superficial, as De Palma is intent on exploring the oddity of conjoined twins rather than telling the story of the murder (the film ends with Phillip’s body still inside of the couch). I think a more apt comparison than Hitchcock is the strangely alluring nightmare of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, another film that portrays morbid fascination with the macabre and is healthiest to view as camp (though Lynch’s film is way more abstract, multi-layered and indecipherable). De Palma’s creative use of split-screen, excessive gore and uncomplicated plot make for an odd little film. It has traces of De Palma’s future success with violent films like Carrie and Scarface; and while it’s probably not a classic itself, it is a fun introduction to a director who would go on to bigger and better, but was unafraid to get a little weird in this early career mystery.