“No mother can do as much for her children as God does for His creatures. You want to refuse all that? You want to give it all up? You want to give up the taste of cherries?”

Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s minimalist Taste of Cherry is an exercise in ambiguity. Its sparse narrative is void of any emotional manipulation and invites the viewer to project their own perspectives onto the meandering conversations. Over the distant drone of construction, car horns, and his own vehicle’s engine, Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi) chauffeurs several strangers in an attempt to find a man willing to assist in his suicide. One after another, he drives these men to the same secluded site where he has dug a hole, requesting that they return the next morning to shovel fresh earth over his body.

He remains confusingly obscure at first, as he rolls down the window of his dusty Range Rover, calling out to random men in the street. He must know that his requests—first, that the men get in the car with him; second, that they perform an unspecified yet simple job for a large sum of money—could easily be taken as soliciting prostitution. But Badii never behaves wickedly. In the brief relationships he has with these men, he focuses on how doing a simple job for him will improve their lives, without ever revealing much about his own.

We never learn of his personal life—his family, his career, his motive. The film could be described as languid or meditative, but slow or boring would not be unfair descriptors either. Its leisurely pace is intentional, as Kiraostami’s filmmaking philosophy indicates that narrative engagement is not one of his goals. In an interview for PBS, the director described his style: “[..] my concentration, my inspiration, was I didn’t want to narrate something, I didn’t want to tell a story. I wanted to show something, I wanted for them to make their own story from what they were seeing.”

He elucidates further in an interview with Dr. Jamsheed Akrami:

I prefer the films that put their audience to sleep in the theater. I think those films are kind enough to allow you a nice nap and not leave you disturbed when you leave the theater. Some films have made me doze off in the theater, but the same films have made me stay up at night, wake up thinking about them in the morning, and keep on thinking about them for weeks. Those are the kind of films I like.

In the opening scene, Badii drives through Tehran, surveying the groups of day laborers congregated on street corners. The window frames Badii as the men crowd around the car, sticking their faces right up to the window as they offer their services to him. Badii drives on, stopping on the outskirts of the city when he becomes interested in a young man who is arguing loudly on a public telephone. His impromptu attempt at a conversation results in the man threatening to physically harm Badii if he does not leave.

His next potential gravedigger is a young soldier (Safar Ali Moradi), who makes it all the way to the gravesite. Badii convinced the young man to accompany him that far by promising six months salary for a simple job. At the site, he explains what the boy must do: simply come back to the same place at 6:00am the next day, call out to him to make sure he is dead, and then shovel twenty scoops of dirt on top of him. “Just pretend you’re farming and that I’m manure to be spread at the foot of a tree,” Badii tells him. But the boy becomes frightened and anxious, eventually jumping out of the stationary car and running away.

Next, Badii is accompanied by a seminarian (Mir Hossein Noori), who feels that he can identify with Badii’s plight. Badii’s dialogue is illuminating: “It wouldn’t help you to know and I can’t talk about it. And you wouldn’t understand. It’s not because you don’t understand, but you can’t feel what I feel. You can sympathize, understand, show compassion. But feel my pain? No.” The student ultimately refuses to perform the task because suicide is forbidden by the Quran. “God entrusts man’s body to him. Man must not torment that body,” the seminarian begins, but his lecture is cut short by Badii. “I’m simply asking for a helping hand,” he says. The seminarian replies, “My hand does God’s justice. What you want wouldn’t be just.” Their discussion, like those preceding and succeeding it, is meandering, unstructured, and has many ellipses within which the viewer has time to consider the subjects they are discussing.

In the last conversation, with an aged taxidermist (Abdolrahman Bagheri) who had contemplated suicide himself in his younger days, the film becomes more lyrical. The elderly man stumbles through a soliloquy vaguely detailing the episode of his past when he was on the verge of taking his own life, and how a simple accident of mulberries rubbing against his hand had saved his life. They were dangling from the tree that he intended to hang himself from, touching his hand as he tied the rope to the branch. He tasted one, and then another; he noticed the gorgeous sunrise; as the children walked past on their way to school he shook the tree so that mulberries fell for them too; and then he took some home to his wife. His story speaks of the wonder of the natural world—from Badii’s perspective, life may indeed be terrible, but the undeniable glory of nature will always be there, a constant source of simple pleasure, no matter the state of despair that we find ourselves in. For the old man, reason to endure does not depend on achievements of the intellect, or creativity, or even personal relationships. The simplest of pleasures are reason enough—even just the taste of cherries is sufficient.

It is humbling to watch this film as an American living in relative comfort, in the same way that it is humbling to travel to a third world country. The film portrays the stark differences between the materially wealthy yet despondent and the poor yet spiritually vibrant—a contrast which is not unique to Iran. Suicide is not as taboo now as it used to be, but it is still largely seen as a shameful and pitiable act done by a desperate person. Badii does not ask for compassion, and his plan is secretive—if he has a family that will mourn his passing, they will be denied the closure of finding his body. To see this empty man—who is willing to pay six months of a soldier’s salary for the simple job of burying him—conversing with a poverty-stricken man who happily supports his family by recycling plastic bags, is sad and convicting; it is a strong reminder that even having the ability to watch this film likely means the viewer is in the top 1% of human history as far as material well-being is concerned. We live in comfort, and in spite (or because) of this, we face existential dread.

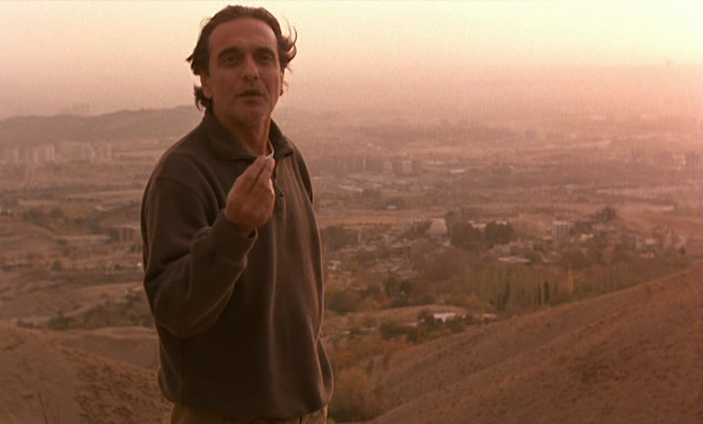

Visually, the film is mostly bland landscapes and closeups, with a few absolutely gorgeous shots sprinkled in. Much of the film is spent inside of Badii’s car, as he and his various passengers alternate occupying the frame. Intercut with these closeups are wide shots of his car traversing the hills as they talk of his situation. The conversations remain at a consistent volume, even when we are viewing the Range Rover from far away. Several times visually striking longshots are used to great effect, subtly romanticizing the dusty sprawl of the haphazardly industrialized capital city and its surrounding countryside.

With a light plot and absent any real character development, the main theme of Taste of Cherry must be the unknowability of the interior lives of other people. Just as Badii tells the seminarian, his pain cannot be felt by others. To further this point, when not in his car, Badii is often behind another intermediary substance—windows, curtains, dust—or seen only as a shadow. In a subdued scene, Badii watches as dirt is sifted through a grate. The quarry’s continuous stream of rock and soil gives Badii a surface upon which to cast a shadow, but when it stops, his shadow disappears. Perhaps this image was included for its novelty or aesthetic appeal, or perhaps it is meant to represent the transitory nature of our being, and how meaning is reliant upon the physical world, unable to be contained solely in the intellectual or spiritual realms.

We never learn what exactly Badii decides to do. We do not enter his apartment, where he decides whether or not to take the pills. As he lies in his grave, drifting off to some kind of sleep, the film bizarrely cuts to grainy, documentary style footage of Homayoun Ershadi smoking a cigarette. The man you may have been feeling sympathy for does not, in fact, exist at all. The viewer is not allowed to even finish the film before contemplating the fact that the characters in it are not real. Mr. Badii is fictional, but, crucially, the thoughts the viewer had while watching his story are not.

When prompted by the thought that his films cause anxiousness in the viewer because they cannot understand what the film is trying to convey, Kiorostami replied: “The beauty of it is that there is no truth to grasp—what you see, what you think—that is the truth and reality. It is what you see and what you think. That is the truth.”

Sources:

Kiarostami, Abbas. “A Conversation with Kiarostami” by Arsalan Mohammad. PBS. 5 January 2009.

Kiarostami, Abbas. Interview by Dr. Jamsheed Akrami. Taste of Cherry, directed by Abbas Kiarostami, 1997. The Criterion Collection.