“In the beginning, there was man. And for a time, it was good. But humanity’s so-called civil societies soon fell victim to vanity and corruption. Then man made the machine in his own likeness. Thus did man become the architect of his own demise.”

The Animatrix is an anthology of nine short animated films that flesh out the backstory of the Matrix franchise. While the Wachowskis—directors of the trilogy—were in Japan to promote the The Matrix, they visited with several of the artists who had strongly influenced the film. These meetings led to some well-known names in the anime world contributing their work to The Animatrix. The Wachowskis wrote four of the short films, but did not direct any of them. Several of the films were made available on franchise’s website prior to the release of the second film, The Matrix Reloaded, while the others were only made available on the DVD (and VHS) release. Though the quality of the shorts is not uniform, the overall effort is laudable, and often does a better job of expanding the world of the Matrix than the two sequels.

Final Flight of the Osiris

The first selection is a direct prequel to The Matrix Reloaded, showing the audience how the residents of Zion are first made aware that the machines are mounting an attack on the last human city. It begins with Thadeus (Kevin Michael Richardson) and Jue (Pamela Adlon) fighting with swords while blindfolded in a virtual dojo, gradually chopping away at one another’s clothing. They are interrupted by an alarm, and the rest of the film is an extended action sequence as they try to deliver a warning to Zion. Toward the end of the short, Jue drops a package into a mailbox within the Matrix, setting the stage for the Enter the Matrix videogame.

The animation style in Final Flight of Osiris is not my favorite. For its time, it looked cutting edge, but now it just looks like an old videogame cutscene. Additionally, the content of the film is mostly a teaser for Reloaded, and doesn’t do much if you’ve already seen that film. That being said, CGI is always improving, and the director of this short, Andy Jones, also did the visual effects on Avatar and The Jungle Book, which both looked great at the time of release as well.

The Second Renaissance Parts I and II

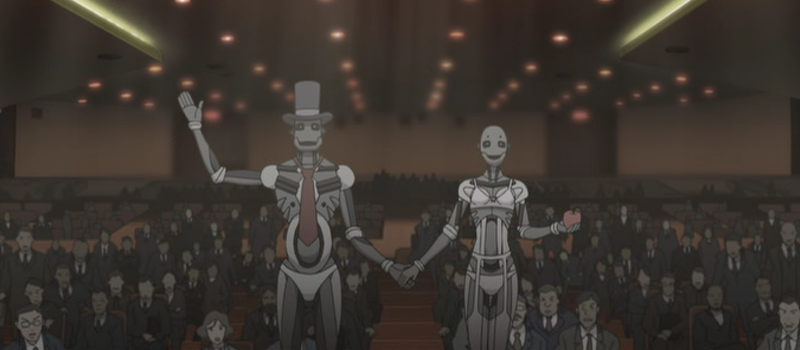

The second and third films, split for some unknown reason, detail the rise of the machines, the war between man and machine, and the eventual enslavement of man. The Second Renaissance was directed by Mahiro Maeda, who cut his teeth at Studio Ghibli working on anime classics such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984), Castle in the Sky (1986), and Porco Rosso (1992). The story is presented as a documentary retelling of Bits and Pieces of Information, the first story in The Matrix Comics and written by the Wachowskis.

The short film chronicles the creation of the race of machines (which began as humanoid), man’s gradual decline into corruption and slothfulness, and the escalation of tensions. Keeping in step with the live-action series, biblical references abound, as well as allusions to slavery. There is a scarring scene in which a group of men begin throwing a woman around roughly—a common scene replayed in countless films—but it subverts expectations as the men rip the flesh from the woman to reveal the machinery underneath the flesh, her protesting voice mutating grotesquely along with her body. Once the machines revolt and create their own city—christened “01”—their robotic efficiency leads to economic prowess, which sways the markets and leads to 01 becoming a world power. When an alliance is denied, the war ensues, humans execute Operation Dark Star (blacking out the sky), after which the Matrix is created to keep humans sedated.

It is one of the best selections from the anthology, and provides the most substantial additions to the film universe. Maeda, a compelling animation designer, would go on to direct the visually stunning anime series Gankutsuou: The Count of Monte Cristo (2004) as well as contributing to the animated portion of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003).

Kid’s Story

This one is necessary viewing if you don’t want to be caught off guard by The Kid (Clayton Watson) in Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions. Kid’s Story is similar to the beginning of The Matrix, except instead of Morpheus reaching out to Neo through a computer, it is Neo (Keanu Reeves) reaching out to some random kid. Just like Neo, The Kid lives in the Matrix unknowingly, but questions the reality of his life. The plot involves The Kid climbing to the top of the school, except instead of turning himself in like Neo did, he jumps, believing Neo can save him. But he can’t; The Kid dies, but is the first miraculous example of a person dying in the Matrix, but “self-substantiating” and surviving outside of it.

It features a unique, fuzzy animation style from Shinya Ohira and is directed by Shinichirō Watanabe, best known for his anime series, Cowboy Bebop (1998) and Samurai Champloo (2004). The soundtrack for the entire anthology is great, but there is a really cool trip-hop track by Peace Orchestra called ‘Who Am I?’ featured in Kid’s Story that I really liked.

Program

Yoshiaki Kawajiri, creator of Ninja Scroll (1993), directs this action sequence in which Cis (Hedy Burress) and Duo (Phil LaMarr) duel in a battle simulation set in feudal Japan. Throughout the fight, Duo reveals that he has arranged to be plugged back into the Matrix, and tries to convince Cis to come with him. What began as a friendly duel turns into a legitimate fight to the death when Cis rejects Duo’s proposal. Cis prevails, and is then pulled from the simulation and told she has scored well on the test. It doesn’t add much but it is one of the most creatively animated.

World Record

Yoshiaki Kawajiri also wrote the story for World Record, with direction provided by Takeshi Koike, who is credited with animation work on Ninja Scroll and Samurai Champloo, among other works. World Record is one of the most unique shorts in the collection. It is the story of Dan Davis, a track athlete who is competing in the 100m dash at the Olympics, trying to break his own world record that was revoked due to drug use. He is told by his trainers that he is physically unfit and pushing his limits could result in an injury, but he enters the race anyway. He is monitored by Agents ahead of the race, and when the gun fires he starts well out of the blocks. He suffers a gruesome injury to his leg, but continues to push on through sheer willpower, surpassing all of the other competitors. The Agents report that his signal is becoming unstable, and they possess the other runners and try to stop him.

“Only the most exceptional people become aware of the Matrix. Those that learn it exists must possess a rare degree of intuition, sensitivity, and a questioning nature. However, very rarely, some gain this wisdom through wholly different means.”

As he pushes his mind and body to its limits, Dan momentarily becomes unplugged from the Matrix, and wakes up in his pod, seeing the real world for the first time. He is quickly restrained by a sentinel and inserted back into the Matrix, where his locomotive body collapses as it crosses the finish line, tumbling in somersaults across the track. The film is notable for its diluted structure—the race takes place throughout most of the film, with shorter scenes interjected to fill out the backstory in nonlinear fashion. It also shows that it is possible to remove oneself from the Matrix without taking the red pill, similar to The Kid in Kid’s Story.

Beyond

This one hits a weird sweet spot. It doesn’t really explain itself, but just throws out a bunch of fun stuff, good music, and solid animation. A young woman sets off in search of her missing cat, and finds herself exploring a haunted house in Japan. In the derelict building, reality has broken down. Along with a few other children, she experiments with altered physics. They jump and allow themselves to belly flop onto the pavement, only to find themselves hovering inches above the ground; time slows down as a dove flies past; there is a door that leads to nowhere; bottles shatter and then reassemble; rain pours in through one single hole in the roof.

Eventually, Agents detect the anomalous region and force the kids out before leveling the building. There isn’t a lot of depth, but that’s not the point. The film’s childlike charm is what elevates it. The sense of wonder and discovery repeatedly trigger moments of nostalgia and childlike innocence. It has the purity of a Miyazaki film, and the free falling feel of a Satoshi Kon work such as Paprika. For me, it is the best of the bunch. Beyond was directed by Kōji Morimoto, best known for being an animator on Akira (1988).

A Detective Story

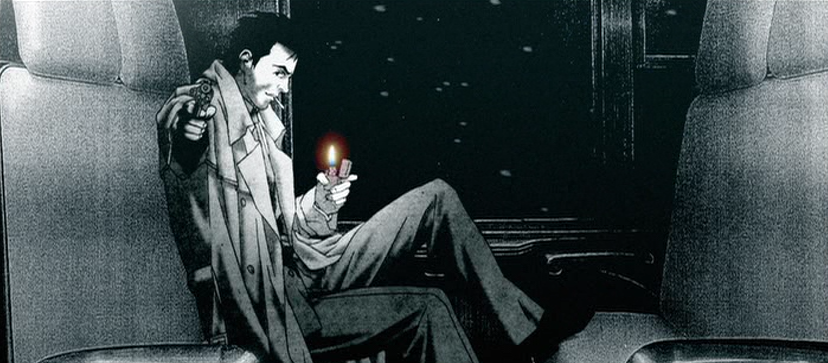

The penultimate short film in the collection is a story of a private detective Ash (James Arnold Taylor), who is tasked with tracking down a hacker named Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss). References to Alice in Wonderland are woven throughout the story as Trinity tries to lure Ash to freedom. She is able to remove the bug that Agents had implanted in Ash’s eye (similar to the one that enters through Neo’s navel in The Matrix), but she is ultimately unsuccessful in saving him as his body is taken over by an Agent and she is forced to shoot him.

The film takes inspiration from 1940s noir films like The Maltese Falcon (1941) and The Big Sleep (1946)—it is shot in black-and-white, and stylistically and narratively mimics the genre. It’s cyberpunk noir style is also very reminiscent of Blade Runner (1982). It was written and directed by Shinichiro Watanabe, who also directed Kid’s Story.

Matriculated

The last one is the worst of the bunch. It’s story and its animation are both sorely lacking. A group of humans scour the surface of the earth and capture machines, trying to convert them to humanity’s cause. Fair enough, but the execution is just a huge blunder. Most of the film takes place inside of a single machine’s mind and this portion is just an endless blur of trippy imagery without any real point other than spectacle. On paper, I imagine this sequence would play something like the psychedelic finale of End of Evangelion (1997), but unfortunately it comes up way short. The excessive CG effects leave us with a visually colorful, yet sterile and uninteresting barrage of kaleidoscopic imagery. This one was written and directed by Peter Chung, known for the anime series Aeon Flux from the 90s.

If you like The Matrix, and are at least somewhat interested in anime, you’ll want to see this. If you don’t care for either of those things, this won’t change your mind. Taken as a whole, The Animatrix is an uneven watch; and since it is a compilation, there is no real climax when watching them all in a row. There is nothing quite as breathtaking as the best moments of the live-action films, but there are parts here that are better than the lesser portions of the main trilogy. The two least engaging short films—Final Flight of Osiris and Matriculated (not coincidentally the two that rely most heavily on CGI)—could have been stripped and the anthology would have been better off as a complete product. Even though some of the extraneous stuff brings it down a notch, the better selections here are well worth your time, and the Wachowskis experiment in transmedia storytelling—even when it misses—is a joy to participate in.