“I still believe in paradise. But now at least I know it’s not some place you can look for. Because it’s not where you go. It’s how you feel for a moment in your life when you’re a part of something. And if you find that moment… it lasts forever.”

Vaguely following the outline of Alex Garland’s novel and echoing its primary themes, Danny Boyle’s The Beach has much to offer in terms of technical craft, but finds itself lacking the rich characterizations and strong narrative pull that made its written counterpart so compelling.1 Moreover, its conflicted presentation, marked by shifting moods and evasive trajectories, prevents the viewer from engaging with the jagged contours of its story, forcing a more clinical approach to the film.

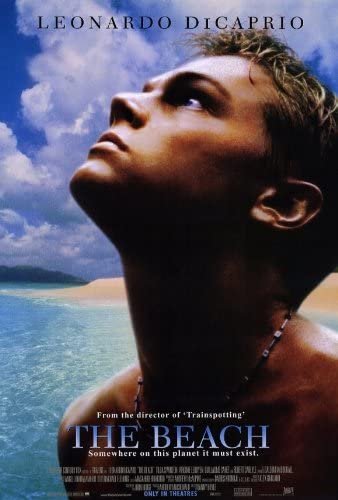

It begins with deliberate evocations of Apocalypse Now as Richard’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) voiceover conveys his life philosophy and settles us into a dingy hotel in Bangkok where he meets his neighbors, the lunatic Daffy (Robert Carlyle) and a French couple, Françoise (Virginie Ledoyen) and Étienne (Guillaume Canet). An apathetic American tourist in search of an adventure to legitimate his transient identity and bring his life meaning, Richard will seemingly say yes to any wild opportunity. To wit, in the opening sequence, he downs a shot of snake’s blood. When Daffy slits his wrists and leaves Richard a map to a paradisiacal beach on a secluded island, Richard cannot but set out in search of it with his two new friends. Reaching the enchanted lagoon after an arduous journey, the trio finds an agrarian hippie commune where nomadic individuals like themselves have turned their lives into endless processions of weed, music, and bonfires.

While narratively generic, this opening portion of the film is entirely serviceable, even great at certain points where a sense of discovery is combined with images of the lush tropics and inspired soundtrack selections. However, it subsequently splits into various unsatisfying threads, none of which jibe with the tone of the opening act. There’s a passionless love triangle between Richard and his French pals, but Richard promptly discards his feelings for Françoise when he has the chance to sleep with Sal (Tilda Swinton), the commune’s benevolent dictator. The newcomers’ presence upsets the uneasy truce between the hippie group and the weed farmers who patrol the island with machine guns, leading to the deaths of several tourists who come to the island with a copy of the map Richard gave them. Pseudo-philosophical monologues are delivered by starlight. A shark attack brings shades of a horror film. None of these ideas are bad, per se, but they’re thrown at the viewer without rhyme or reason and most of them languish until the film’s final act, which sees Richard turn into a wild-eyed rogue who goes insane and becomes “one with the jungle.” Morally unmoored by his passionate hedonism, Richard suffers a psychological breakdown and begins experiencing hallucinations of Daffy and envisioning himself as a character in a video game.

In the pursuit of myriad ambitions—to enchant the Leonardo DiCaprio heartthrob crowd, to capture the sense of wanderlust and the high of serendipitous discovery, to warn against the pursuit of an ideal, to be both meditative and edge-of-your-seat thrilling—The Beach is occasionally revelatory but ultimately collapses beneath its own weight. There are hints of a better movie here; maybe even several. In fact, that might be its primary problem: that just like its impressionable protagonist, it has no core identity and thus finds itself pulled in too many directions at once, to its ultimate detriment. An interesting failure, marked by many good ideas that are poorly integrated, but a failure nonetheless.

1. It’s been about a decade since I read The Beach as a receptive teenager. I’m not sure how it would sit with me if I read it again now. Methinks I’d still connect with it.